Having received my copy of Doug Morrissey’s latest work later than some of the other readers of this Blog, I understand now, having read it, why none of them volunteered to write a review of it for me. “Selector Squatters and Stock thieves” is not an easy book to read. It’s not so much an exciting tale of bushranging, the police chase, personalities and persecution, like most other Kelly books – Morrissey’s earlier one included – but instead is a very much drier and detailed examination of the entire social and economic environment of the time, the actual times and the actual place and the actual context in which the outbreak sits.

There was a discussion about this context as far back as the landmark Kelly symposium in Wangaratta in 1967, where Ian Jones set out a view which has remained mostly unchallenged inside the Kelly mythology till now, that the difficult and divisive social and economic conditions at the time, and particularly selector poverty and the land wars between selectors and squatters were the seed bed for the Outbreak. From the floor at the symposium Jones view WAS challenged – by Weston Bate, an actual historian – but Jones brushed Bates objections aside saying “We are in happy disagreement”. McQuilton developed Jones idea further with his 1979 book The Kelly Outbreak in which he advanced the idea that Ned Kelly was a ‘social bandit’ – an almost accidental popular leader who emerges out of the sort of poverty and widespread social and political unrest Jones postulated was afflicting the north East during that era.

In 1987 Doug Morrissey completed his doctoral thesis “Selectors squatters and Stock Thieves : A Social history of Kelly Country” at Latrobe University. It remains unpublished but ‘extensively revised and brought up to date with new research’ it forms the basis for this new book. In this book, Morrissey challenges the orthodox ‘Kelly legend’ view and offers a much wider overview of the district and its political, economic and social history than the very narrow and focussed perspective usually seen in the Kelly literature. According to the Kelly legend the north east was divided along strict ethnic, class and religious lines: Irish settlers were patriots and opposed the British, Catholics and protestants shunned one another, the poor selectors were at war with the wealthy squatters over land rights, police were the mercenary enforcers of squatter rights, and Ned Kelly emerged from a typical poor Irish selector background to become the people’s hero. This portrait, according to Morrissey is supported by a highly selective narrative which ignores the historical realities that he documents extensively in this book. Catholic Ellen Kelly, for example, married a protestant and so did her daughters Maggie and Annie – and Annie later had an affair with a policeman. The reality was vastly more complex than the Kelly legend and its proponents would have us believe. The Kelly scenario of widespread selector failure, poverty and disquiet, the sense of being under siege and oppression by police and squatter, the idea of the north east being a seething politically volatile hothouse ripe for revolution that was rescued by Ned Kelly – Morrissey shows that’s all a fantasy. Yes, there were disputes, there was drought, there was crop failure and individual failures – but in the main the place was going forward, people were making their way ahead by hard work and community support of its varied constituents. The Kelly outbreak was pure criminality that emerged out of a fringe of larrikins and shanty dwellers who repelled the majority of the population of the north east.

The book of over 350 pages is divided into three parts: Social order and authority, Land settlement, and Crime and Policing. With respect to the prevailing social order Morrissey makes it very clear that the Lloyd/Quinn/Kelly clan were not in the least bit representative of the typical inhabitants of the north east: “Notions of respectability and decent public behaviour were taken seriously by the majority of the regions inhabitants”. They would not have approved of what Morrissey terms the ‘shanty culture’ of the Kelly clan, a life that revolved around the ‘shanty’, a communal meeting place that was the focus for a life centred around drinking, riotous living and larrikinism, and was associated with criminality of varying kinds – petty crime, sly grog selling, prostitution, stock theft.

Instead the majority of selectors were extremely hard working and stoic in the face of the physical challenges, including drought that faced them all out on the isolated borders of settlement. The typical selector was a hardworking, upstanding church-going member of local communities who respected the rule of law and traditional values. Even the ones who identified as Irish, and supported home rule for the Irish back home upheld the rule of British law in the colony. Selectors were noble folk in the main, breaking in the land and for many attempting a profession they had no prior experience of: according to Morisseys figures 37% of selectors in the districts that he studied described themselves as labourers and another 21% were such things as school teachers, miners and carpenters. Morrissey’s discussion of land acquisition under the constantly evolving legislation shows how selectors took advantage of the opportunities, and how frequently they were successful – he challenges a claim that only 37% of selectors in the north east were successful, with his own figures derived from an analysis of 265 selections made between 1868 and 1880 showing that ten years later 78% were still on their selections and 72% eventually acquired the titles to their land. All things considered, these are noteworthy outcomes.

In the third section of the book Morrissey reviews the criminal history of the clan, and discusses the complex relationships between police, the criminals and their informers. The full story of the Kelly ‘villains’ Hall and Flood is detailed, and was news to me, but Morrisseys view of Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick, is a view which he elaborated in his first book, and is wrong. I think he is close to the truth in portraying Fitzpatrick in some way as a ‘mate’ of Ned, but he fell into the trap of accepting Corfields entirely erroneous claim that Fitzpatrick died of cirrhosis of the liver. This trap has the effect of making the earlier and otherwise entirely unsupported claims about Fitzpatrick being a drunk easier to accept, and this then leads on to an acceptance of other equally unsubstantiated claims about Fitzpatrick, such as that he was a womaniser. Consequently Morrissey’s view of Fitzpatrick as a ‘scheming policeman’ is not one supported by the evidence.

That however is not my sole or even my main criticism of this otherwise very detailed comprehensive and informative book. My main criticism is that once again Morrissey has dispensed with even the slightest attempt at a bibliography or referencing, instead alerting us by italicising the words taken from elsewhere, but not providing even the slightest hint about where from. Morrissey simply expects us to take his word as gospel. He hasn’t provided us with the opportunity to explore further or to check up on what he claims is the case. This failure borders on contempt for his readers, and is a huge pity. Surely Morrissey knows that this book contains material that will be highly contentious in certain quarters, and the Kelly myth-makers will be desperate to discredit it. Unfortunately, by not providing any references he has given them the excuse they want, an excuse to reject everything he says in the book that they don’t like as just his opinion – and that will be almost all of it!

This is in fact a really good book. It’s another step forward in the deconstruction of the mythology about life in the North East in the 1870’s, and further erodes what little remains of the case for Ned Kelly being the people’s hero from the north east. He was in fact a clever, violent and vengeful criminal whose support was non-existent once the money ran out, as is evidenced by the families inability to obtain the excellent services of barrister Mr Hickman Molesworth to defend him in Melbourne.

(Visited 954 times)

Ex-Constable Fitzpatrick was never in prison! (Part 1 of a 3 part post)

Doug Morrissey in his new book, “Ned Kelly: Selectors, Squatters and Stock Thieves” (p. 273), says that “there were two men named Alexander Fitzpatrick. … The prison photo looks nothing like our Fitzpatrick.” That’s what I thought when I first saw the prison photo and compared it with Constable Fitzpatrick’s carte-de-visite. But I was pushed to allow the possibility that they might be photos of the same man by a number of people making comparisons between details in Fitzpatrick’s police Record of Service, and the prison record of the man gaoled in 1894 for passing valueless cheques.

There are four common elements between Constable Alexander Wilson Fitzpatrick’s police Record of Service and the record for the prisoner named Alexander Fitzpatrick. These are the first name and surname (there is no middle name in the prisoner record), grey eyes, born in Victoria, and of Presbyterian religion. Both men could read and write.

However, there are significant differences that make the equation of these two records at minimum problematic. These are year of birth, height, marital status, hair colour, and identifying physical marks. I have put them in table form below, but it will be out of alignment here:

Source Age Height Marital Status Hair Particular Marks

Police Record of Service B. 18 Feb 1856 5’9½“ Married, 10 July 1878 Light Bullet scar on left wrist

Prison Record B . 1858 5’9” Single Brown Scar on left side of head

Comparison of the details shows that Prisoner Fitzpatrick was two years younger than Constable Fitzpatrick record, was half an inch shorter at age 36, had different hair shading, is recorded as single under martial status, and had different scarring. There is no question that the bullet scar on Fitzpatrick’s wrist from the Kelly incident in April 1878 remained visible. When reporter Brian Cookson interviewed him in 1911, Fitzpatrick said that the bullet fired at the Kelly house had struck his left wrist and ‘entered just on the edge of the knucklebone, where the mark still shows, as you [Cookson] can see’ (Cookson, p. 93).

In addition to the above differences, Constable Fitzpatrick married his wife Anna (nee Savage) in 1878, had three children with her, born 1878, 1889, and 1904, and stayed married for the rest of his life (Corfield, “Ned Kelly Encyclopaedia”, p. 166). The prison record shows that Prisoner Fitzpatrick was sentenced on 16 June 1894, received into Melbourne Gaol on 16 July, and released from prison on 1 June 1895. The imprisonment falls between the births of ex-constable Fitzpatrick’s second and third children, yet there is nothing anywhere to suggest any disruption in his married life. Significantly, we hear no mention of ex-Constable Fitzpatrick having been gaoled by those who hated him most, viz., Mrs Kelly and Jim Kelly, interviewed by Cookson in 1910. Similarly, Tom Lloyd Jr. was the principal informant for J.J. Kenneally’s “Inner history of the Kelly gang”, compiled in the late 1920s. Both Kenneally and Lloyd clearly loathed Fitzpatrick, but again there is no mention of his being gaoled.

Fitzpatrick never did gaol time! Part 2 of a 3 part post

Further, the prison record gives Prisoner Fitzpatrick’s occupation as ‘farmer’. This correlates with a Gazette Notification in the Bairnsdale Advertiser in January 1891 that an Alexander Fitzpatrick was approved for a lease under the Land Act, (20 January 1891, p. 3, Gazette Notifications, ‘Applications for Leases, under Section No. 2, Land Act 1890, Approved. … Alexander Fitzpatrick, 228a, Murrungower.’). Again, there is no connection with ex-Constable Fitzpatrick, who became a travelling salesman, not a farmer. This is concrete evidence of the existence of a second man named Alexander Fitzpatrick in 1891. Three years later, a note in the Newcastle Herald from 25 June 1894, p.5 reported that ‘Alexander Fitzpatrick, calling himself a farmer, was arrested yesterday for passing valueless cheques’. The date is retrospective, but he is identified as a farmer, as with his later prison record.

On 20 June 1894 an article appeared in the Ovens and Murray Advertiser, p. 6. It gave an account of the court appearance of the man who “answered to the name of Alexander Fitzpatrick”, and provided a short summary of the April 1878 incident at the Kelly’s house including that Fitzpatrick “is the mounted constable who was shot by Ned Kelly”, and said that “He was remanded for the production of further evidence”. It seems that variants of the story, which had incorrectly identified the arrested Alexander Fitzpatrick as ex- Constable Fitzpatrick, were repeated with various words in a range of regional newspapers. Thus the Camperdown Chronicle 26 June 1894, p. 2, reported, “A CRIMINAL WITH A HISTORY. A man named Alexander Fitzpatrick was brought before the Fitzroy court this morning on a charge of obtaining money by false pretences, and remanded for the production of further evidence. Fitzpatrick was the constable who went to arrest Ned Kelly before he took to the bush and was shot in the wrist.”

The incorrect identification added colour to the story, and, as Fitzpatrick told Cookson (p. 94), there were a number of such stories: “A man was arrested for drunkenness or some other minor offence at Korong Vale, in the Bendigo district, and he said he was ex-Constable Fitzpatrick. A Bendigo newspaper printed a paragraph, reflecting on my character, and I issued a writ for £1,000 damages. My legal advisers, however, said that I would have to show that I suffered some loss in consequence … before I could succeed, and reluctantly I had to abandon the action. Every now and again, for years afterwards, I had to stand up and defend myself against unjust accusations”. So we also have the reason why Fitzpatrick had to forget about suing for libel.

The Age added further to the idea that farmer Fitzpatrick was the same man as ex-Constable Fitzpatrick when it reported on 10 July 1894, p. 7, “ALLEGED FALSE PRETENCES. At the City Court yesterday, an ex-constable named Alexander Fitzpatrick, who will be remembered in connection with the origin of the Kelly gang outbreak, appeared to answer two charges of obtaining money by false pretences from Hannah Ryan ….The accused was committed for trial on both charges.” The identification of the two men as one was now complete. Upon his conviction, a string of newspapers published a note from a wire news service in the vein of the Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 17 July 1894, p. 4, “Intercolonial News. [By Telegraph.] Victoria. Melbourne. Tuesday Afternoon. Alexander Fitzpatrick, who figured conspicuously in the Kelly gang outrages, was sent to gaol to-day for 12 months for obtaining money on false pretences from Bourke-street publicans.”

Fitzpatrick never did gaol time! Part 3 of a 3 part post

The false cheques were drawn on the Colonial Bank, Orbost (Snowy River Mail and Tambo and Croajingolong Gazette, 7 July, 1894, p. 3); farmer Fitzpatrick’s 1891 land lease was at Murrungower (Murrungowar), some 40 km north-east of Orbost. The paper described him as “a former resident of this district” and also held him to be the ex-Constable. Yet ex-Constable Fitzpatrick did not take up a farm somewhere east of Orbost. Corfield writes that “After leaving the police, Fitzpatrick moved to 68 Liddiard St, Hawthorn, his occupation being listed as ‘traveller’” (p. 165). This review of the evidence shows that the imprisoned farmer Fitzpatrick was not ex-Constable Fitzpatrick: they were two different men. This should have been be clear enough from the first, from comparison of the descriptive details in Alexander Fitzpatrick’s prison record with Constable Fitzpatrick’s’ Record of Service.

It looks like I too was misled by the push to identify these two men as one and the same by privileging mistaken news reports over government records. Bu no more: I am undeceived, and can now confirm they are different men. Ex-Constable Fitzpatrick never did gaol time. The mistake, as they say, was made by a reporter; apparently beginning in the Ovens and Murray Advertiser.

Oh My GOD!

This is a sensational piece of sleuthing Stuart, absolutely incredible and completely convincing. You've got much further than Morrissey did in proving there were indeed TWO Fitzpatricks. We have all been misled.

I think this should be a Post to the Blog, so with your permission I will put it up at the end of the week with your chart and maybe a map – I had no idea where Orbost was.

Well done, Stuart!

Even Blind Freddie could tell the prison Fitzpatrick wasn't the ex-Constable!

Another Kelly falsehood bites the dust!

Hi Dee, you can do the above as a whole post if you like, but I can't see much point as it is already here! It was Morrissey's definite assertion that there were two Alexander Fitzpatricks that got me motivated to re-examine the whole thing, and he was right. I know it's frustrating that he doesn't provide referencing, but that doesn't mean that he doesn't know what he is talking about, or that he hasn't based his book content on thorough research. As I pointed out yesterday, his views about Fitzpatrick being a womanising larrikin are drawn directly from Molony's 1980 book, which counted as reputable scholarly research (until various serious errors were exposed relatively recently). And the massive value of Morrissey's new book is not the two pages that mention Fitzpatrick, but the 300 pages that totally demolish the longstanding nonsense about a war between squatters and selectors, that he shows was over nearly a decade before the Kelly outbreak, and the nonsense about any Irish separatism in NE Victoria when in fact the Irish mostly regarded themselves as British, as did the Welsh, Scots, etc. He blows several major longstanding Kelly myths totally out of the water, that were long overdue for review.

Hi Horrie and Alf, it seems that bind Freddy worked at the Ovens and Murray Advertiser back in June 1894. But importantly, that means that all the newspaper "evidence" about Fitzpatrick being an alcoholic falling for "the flowing bowl" that was published in 1894 is totally wrong, as it applies to farmer Fitzpatrick, not ex-Constable Fitzpatrick, who was busy working as a salesman. I will write to the Old Melbourne Gaol and let them know about the error they are perpetuating by identifying the ex-Constable incorrectly as the gaoled failed farmer. This also shows how easy it is to fall for myths, as the chain of newspapers who were quick to link the fraudulent cheque passer wit the wrong man shows.

Those very few of us who have copies of the original Morrissey doctoral thesis, have his citations and annotations anyway. Many modern historians are disgusted by how imitators shamelessly steal their research, and lift their hard-earned archival quotes. It's a pity Morrissey quoted Corfield's mistake about Fitzpatrick's alcoholism, but his original research among the PROV records was exacting and peerless. Nobody else delved so far into the original records.

Hi Ian, yes, Morrissey's thesis source notes are very detailed and exacting. I don't know where the story about Fitzpatrick dying of cirrhosis originated but it must predate Corfield, as his Encyclopaedia is a compilation from many sources and yet he doesn't cite the death certificate. The story of Fitzpatrick as an alcoholic goes back to the Kelly slurs in 1878 as we know, and was accepted by practically every writer about Kelly ever since, without a second thought (or any thought at all). As someone said on Dee's blog last week, it would be nice to know where the cirrhosis story originated. My suspicion is that someone saw the death certificate states liver complications, but had no idea what sarcoma was, and let their anti-Fitzpatrick bias interpret it as cirrhosis. Whoever that first misinterpreter was, they sure found a large and uncritical audience of enthusiasts to repeat it.

it’s unforgivable that Morrissey provides no footnotes or references – his history is no such thing without them and how did he get his doctorate without knowing or being committed to solid sourcing?

his writing style is slip-shod and his claims come across as folk lore or rumours

he is a very poor exponent of Kelly contrarianism

Same goes for Max Brown’s ‘Australian Son’ and that dreadful Brad Webb book. At least Morrissey knows what he is talking about. The other two are almost entirely folk lore and rumours.

I recently read Doug Morrissey’s Selectors, Squatters and Stock Thieves for the first time. I made the mistake of reading The Stringybark Creek Police Murders first, which, I must say is the worst produced book by an author touting his academic credentials that I’ve ever come across. However, in Selectors Morrissey’s clear explanation of the evolving series of Land Acts and their impact on selectors’ lives was particularly interesting, and I appreciated the picture he paints of the complex social world of early European settlement in the North East. And he did include an index in this one, but unfortunately no footnotes or bibliography.

I can’t see, though, that he “blows McQuilton out of the water”, to quote Stuart. It seems to me they each place emphasis in different areas of the same material. Morrissey shows that eventually most selectors, through very hard work, achieved their goal of a farm for their families, which I imagine McQuilton would agree with. McQuilton, though, emphasises how things were for selectors around 1878, when there was, demonstrably, considerable hardship. Morrissey claims the Squatters world was in decline by the mid 1870s, but gives ample evidence that they still exerted considerable power in the small communities. McQuilton places his emphasis on the impact of that retained power leading up to the Outbreak.

The question about McQuilton’s work is whether the hardship facing the selectors, at that time, translated into support or sympathy for Kelly.

The question for Morrissey is whether there was a claimed widespread fear of the Kellys which would explain the inability of the police to catch the Gang.

Morrissey hangs his argument of that widespread fear on the evidence of Jacob Wilson, and its at this point that I have real reservations about Morrissey’s work.

Having read through Jacob Wilson’s Lands Department file Morrissey must know that Wilson wasn’t telling the truth when he answered the question of the Royal Commissioners: Have you been driven out of your land solely in consequence of what you did in the Kelly matters? Wilson replied: Most decidedly (Question 4529). Wilson lost his land because he failed to repay a long-standing debt. He had effectively lost control of his land some weeks before Stringybark, about the time he had a police agent staying with him to watch the Lloyds. That was in June 1880. He remained illegally on the land, an isolated block four miles from the nearest road, for another four months – all the while claiming that he was terrified of the Kellys. He finally left the land on the 17th October 1880. His land had been sold at Sherriff’s Auction in mid-July after which he had no right to it at all. Since 1978 Morrissey has continued to insist that: “Jacob Wilson…was constantly harassed and menaced by active sympathisers, so much so that he sold his selection and left the district” (Ned Kelly’s Sympathisers, Historical Studies, Vol. 18, 1978, Issue 71, p. 288.) Which is nonsense. Wilson was making up a story in order to get compensation. Morrissey goes along with his claim, even though he knows that the true story is far more complex than Wilson was prepared to admit.

Morrissey plays games too with Wilson’s testimony before the Commission in other ways – in order to prove that Wilson was brutally dealt with by the Kellys. For example, he claims that “ on one occasion, several sympathisers, who obviously enjoyed unsettling the old man, visited Wilson in the dead of night simply to increase his fear of them.” What really happened was something quite different, and which is obvious to anyone thoughtfully reading Wilson’s evidence. Morrissey omits from his account that it was two known Kelly supporters who were carting a (presumably stolen) plough, in the middle of the night, from Kilfeera towards Lurg. In attempting to cross Wattle Creek (Wilsons hut was fifty yards from the creek) their dray became stuck. They had a problem: they’d stolen a plough, presumably it was being taken to Tom Lloyd’s place a mile upstream of Wilson’s, and presumably they knew what it was to be used for. They needed Wilson’s help, and they weren’t interested in explaining what they were doing carting a plough across country in the middle of the night. Wilson was understandably frightened at being woken. He had recently sold hay to a police patrol and he clearly thought the Kellys had come to get him. But all that happened was that “they asked me to see them across the creek”. They asked him! Clearly they hadn’t travelled all the way out to Wilson’s place just to torment him, as Morrissey would have us believe.

Morrissey makes a lot of Wilson once having to hide in a cherry tree to escape the Lloyds. Morrissey’s version is that “ Wilson had spent a fear-filled night in a cherry tree, too scared to come down after being chased by the Lloyds and their dogs: Jacob Wilson the Lloyd watcher became Jacob Wilson the Lloyd persecuted.” This is pathetic history writing. Wilson was in the cherry tree because he had crept a mile through the bush from his place, in the middle of the night, to spy on the Lloyds. The Lloyd’s dog had heard him and the Lloyds and (he claimed) Dan Kelly had rushed out to see who it was. They sooled the dog and Wilson climbed the tree. Wilson says, quite openly, that they didn’t know it was him and that they thought it was the police. The dog never found him. He got away. Dan Kelly didn’t come to get him, even though they all knew where he lived (he was the Kelly’s closest neighbour to the south-west). Nothing suggests that the Lloyds went out of their way to harass Wilson. They were chasing an unknown intruder.

Keen to show that the harassment of Wilson was constant, Morrissey dates this incident as being “a few days” before another incident, equally contentious, which Wilson says led to him finally leaving his block. That was in October 1880. By that time Dan Kelly had been dead for months.

Clearly Wilson was frightened, although not enough to leave the land that was no longer his. He may well have exaggerated his plight in the same way that he falsely claimed that his leaving Lurg was entirely due to Kelly harassment.

Common sense suggests that there were people in the North East who were afraid of the Kellys. But to have to omit details and exaggerate others in order to make an argument is poor history writing, to say the least. “A disgrace to historiography” is what Stuart likes to call similar claims made about Ian Jones’ writing. That’s probably a bit over-the-top in both cases, but I can see what he is getting at.

For Morrissey to move from Wilson’s dubious testimony to the claim that vicious behaviour by the Greta Mob kept the North East in fear of supporting the police is quite a stretch, and having to fiddle the books to make the point is disappointing.

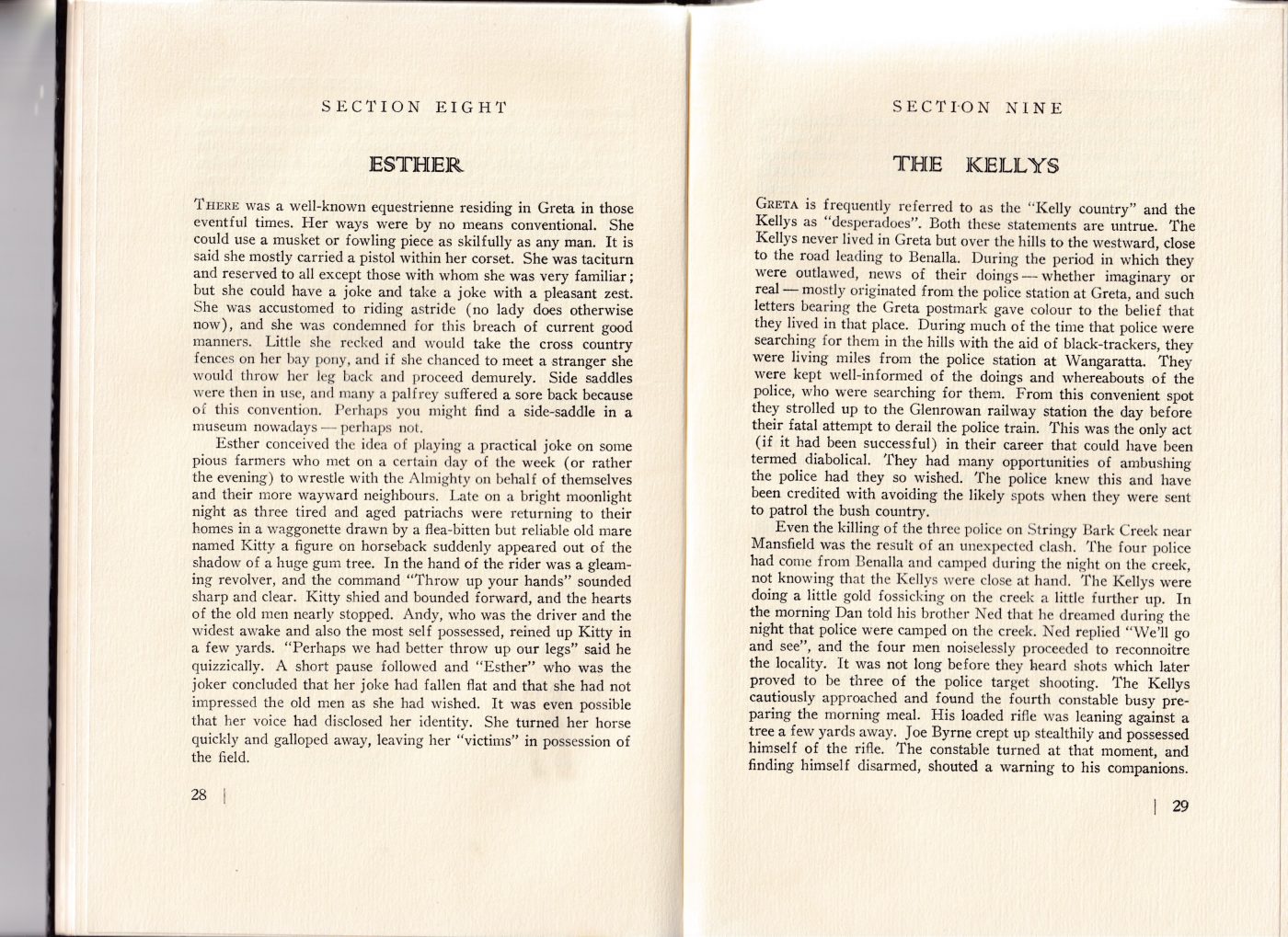

The other thing that Morrissey doesn’t tackle is the alternate view; that sympathy for Kelly could have been a factor explaining the lack of support for the police. I was interested to see what he would say about S.E. Ellis’ A History of Greta (Benalla Historical Society, Kilmore 1972). He must have read it, having completed a study of the Greta district. Without a bibliography, though, no one knows. Ellis was one of Morrissey’s good people. He was born in 1873, raised in Greta, the son of Thomas Ellis the Greta Post Master. His parents were devout members of the Church of England. His Uncle, also Samuel Ellis, was a founding member of the Primitive Methodist church in Greta. He attended Greta Primary school, won a scholarship to Scotch College in Melbourne, became a teacher, a storekeeper, and eventually took up the farm of his wife’s uncle John Dennet, an early Greta selector. He took services in the Greta Church of England when the pastor was unavailable. His history, written around the 1930s, was for local consumption. He writes to remind his community of how things were in early days and he clearly expects his local readers to nod in agreement with him. In writing of the Kelly Outbreak he states quite simply: “People in the neighbourhood showed no fear of being molested and went about their duties during daylight and darkness.” (p.31). You would have thought that Morrissey, as a serious historian, would need to explain how he accounts for this claim, contradicting as it does his own argued position that the Greta Mob had the population trembling. But Ellis gets no mention.

All in all, Selectors, Squatters and Stock Thieves, is worth the read if you’re interested in the rural history of the area, and you don’t mind the absent footnotes and bibliography – although you’ll miss their reassurance… especially as his work is sometimes pretty sloppy.

Thanks for such an interesting comment Perc. What you’re pointing out about Morrissey is important – his selective use of evidence to make a case weakens his authority considerably, and I agree with your view of his SBC work, #3 of the trilogy – its almost unusable as a reference. In some respects Morrissey has become a hindrance to exposing the real story, by his lazy scholarship and by his partisan promotion of particular unsupported views of his own, all of which just muddies the water.

In regard to why nobody seemed to support the police effort to track the Gang down, wouldn’t that be exactly why nobody was in fear, as reported by Ellis? What I am getting at is that according to Kelly himself people were safe as long as they went about their ‘duties’ and kept out of the way of the Gang and didnt involve the police? They just minded their own business. But the police murders shocked and traumatised the entire colony – there cant be any doubt about that, and many people were scared and afraid of the Gang as a result. Notwithstanding all his other issues , Wilson may still have been terrified of the Kellys, though spying on the lloyds was asking for trouble!

I agree, David, Wilson was certainly anxious about the Kellys – the murders were no doubt in the back of his mind. But not worried enough to leave, which is strange. He knew they suspected him, but he also knew they didn’t actually know what he had done. Was he reasonably confident that all they would do is call him an old bastard? Who knows.

And agreed, Ellis is saying that if you went about your business you wouldn’t be bothered by the Kellys. But he doesn’t suggest that this was from fear. His tone , and his emphasis on “day and night” suggests something more to me… perhaps that the locals were confident of their safety because they had no intention of acting against the Kellys. For a pillar of the Greta Christian community, writing a history of Greta, not to express concern about the thieving and the killings, or the planned killings, is odd. Ellis makes light of the Kelly’s criminality – which leaves me wondering what was going on the community which allowed that view of Kelly to be held. That seems to me to be a type of sympathy.

Ellis’ chapter on the Kellys (pp. 29 – 32) includes a particularly Kelly-partisan explanation of the Stringybark killings – which was the result of “an unexpected clash”. He spends a page making fun of police incompetence, and explains that Glenrowan was not planned to kill and awe the police! It isn’t good history, but as a piece of history in itself it, reflecting the view of a local god-fearing man, it ought not be ignored. A decent historian attempting to weigh the issues of fear of the Kellys versus support for the Kellys ought to at last acknowledge Ellis’ position.

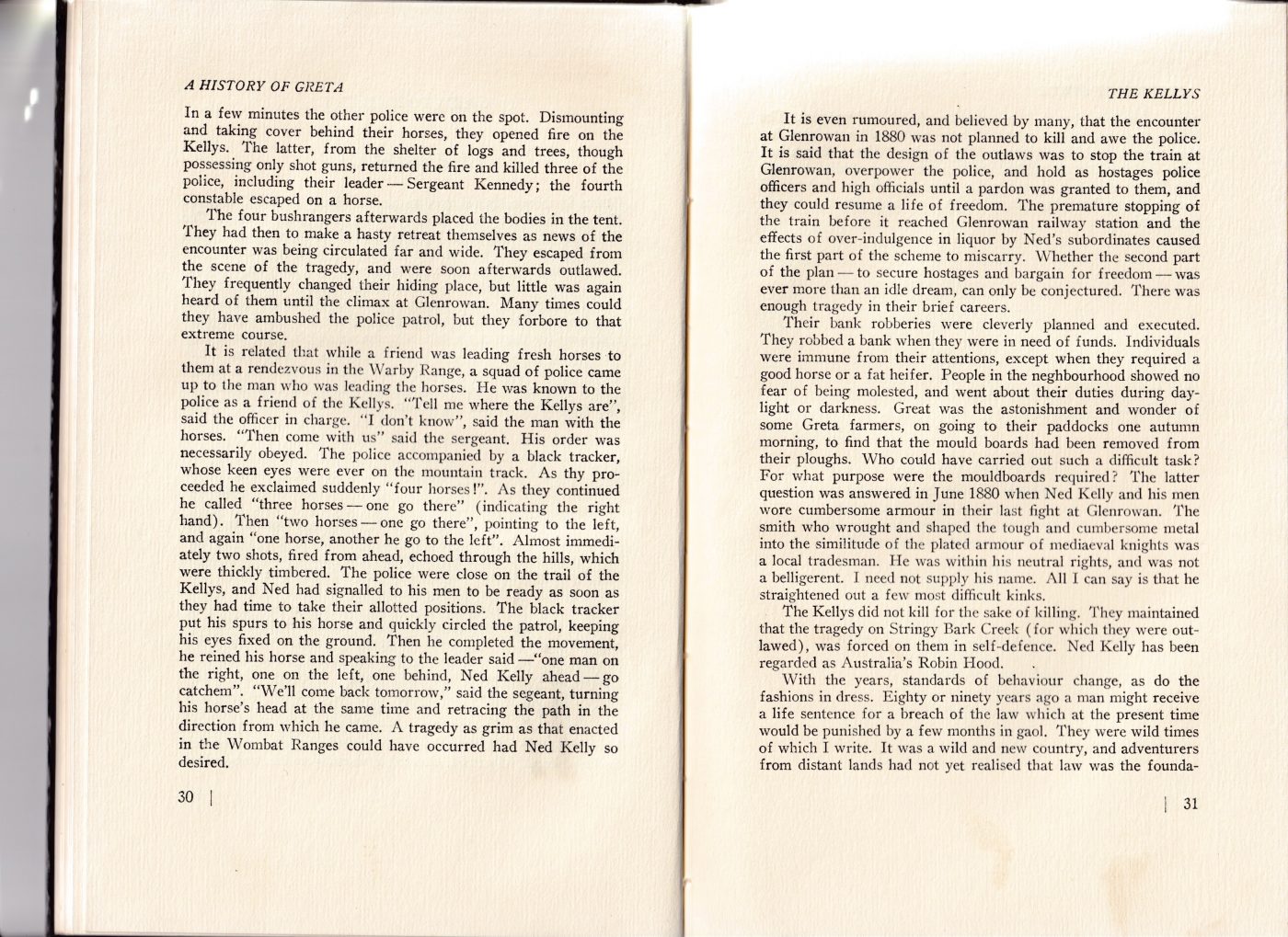

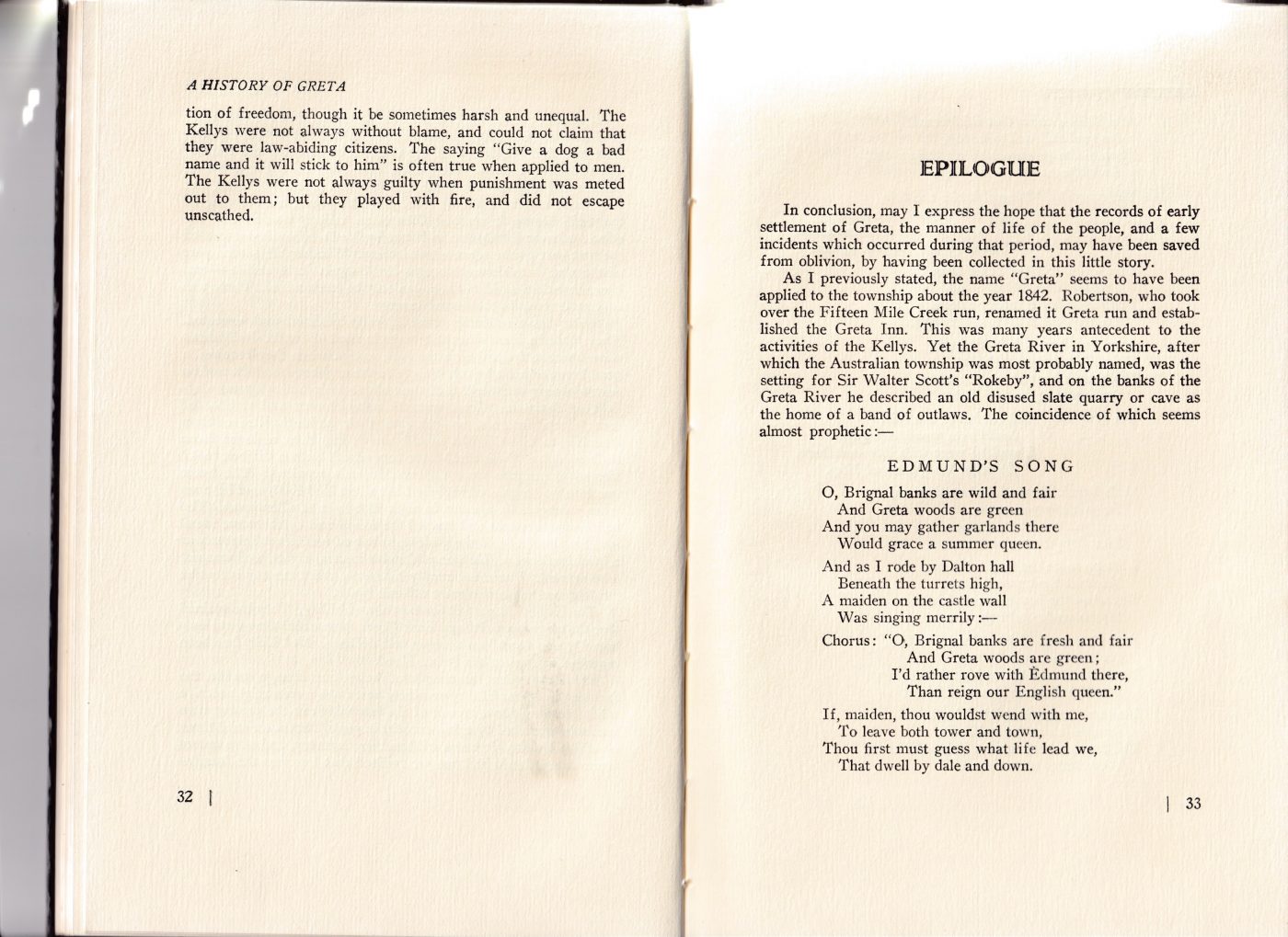

Ellis’ concluding remarks on the Outbreak are puzzlingly ambiguous too, for a good Christian man. Ellis writes: “They were wild times of which I write. It was a wild and new country, and adventurers from distant lands had yet realised that law was the foundation of freedom, though it be sometimes harsh and unequal. The Kellys were not always without blame, and could not claim that they were law-abiding citizens. The saying “Give a dog a bd name and it will stick to him” is often true when applied to men. The Kellys were not always guilty when punishment was metered out to them, but they played with fire, and did not escape unscathed.” It suggests to me that there were people in the district who were seriously conflicted by the Outbreak – caught between their commitment to the community, and their understanding of where Kelly was coming from. I’d suggest too that there is a lot to unpack in it, as an historical document in its own right. Its disappointing, and perhaps indicative of Morrissey’s shortcomings as an historian, that he completely ignores it.

In an epilogue to his book Ellis reproduces in full one of Sir Walter Scott’s border ballads – which romanticise the Scottish borderland brigands who stood against the English. Some at the time felt them to be treasonous. The one Ellis quotes is called “Edmund’s Song” and features a brigand roaming where “Greta woods are green”. Ellis comments that the coincidence “seems almost prophetic” . The brigands and rapparees, you’d remember, were lionised and protected by the peasantry – much as Hobsbawm observes elsewhere, and much as McQuilton suggests may also have occurred in the North East. We’ll never know how far Ellis was drawing parallels, but it is a strange addendum.

I can’t imagine that Ellis would have ever considered actively supporting Kelly. In fact if placed in Curnow’s position you would have to hope, given his beliefs, that he would have acted in the same way. Strange then, that he presents such a sympathetic view, long after there was any need, if ever there was, to pretend sympathy out of fear.

So we agree David, there must have been fear, and probably widespread fear, but there was also “sympathy,” and perhaps that was widespread too.

Hi Perc, I gather from the above there are only 4 pages on the Kellys in that Elllis book, which according to the NLA catalogue was just a 500 copy print run back in 1972. Any chance of scanning and uploading them for us researchers? It sounds like that would be 2 images only. I can’t find it online.

Hi Perc, this is a fascinating summary of Jacob Wilson’s involvement with the Kellys, especially about hi remaining illegally for four months on what used to be his land before it was sold at Sherriff’s auction (based on Land Department files), the while claiming to be living in fear of the Kellys (RC Q. 4527-4529; 4544-4560; 4588-4598); and of his hiding in a cherry tree while eluding pursuit after spying on the Lloyds in the middle of the night although they did not know his identity (4475-4488); and that two men asked his help when crossing the river towards Lloyds’ with a stolen plough in the middle of the night which is not like they went to his place to harass him Q 4457-4463).

We know that Wilson gave information to the police (Q. 2109-2115; 4471), but he was also afraid that sympathisers might have a down on him if he gave or sold hay to police for their horses (Q. 4446), in other words seen to be aiding the police (Q. 4489-4492). Supt. Nicolson testified that Tom Lloyd had abused Wilson to him as a personal enemy and said he had his eye on him (Q.4657-8); Wilson has a policeman put up in his house for a fortnight (Q. 4516-22). He wanted his son to join the police, for which the son was harassed by sympathisers (Q.9825). He wanted compensation for what he saw as his losses caused by his aiding the police, and even asked the Commission to try and secure him a job (Q. 10016-20). So one question is to what extent was Wilson afraid of the Kellys. I think that because of the above it was to a greater extent than your three contrary examples suggest, but I think you make a good case (based on Land Dept info which I haven’t read) that Wilson may have been too generously treated by Morrissey as evidence of sympathiser harassment.

But even if Morrissey fails to persuade from the Wilson case that there was widespread fear of the gang and sympathisers in the north east, that is only one person’s case; and there is much other evidence of widespread fear of the gang and sympathisers by average citizens totally uninvolved with some active police-supporting activity such as spying on the Lloyds or others or putting up coppers for a time. There is plenty more than Wilson in Morrissey’s Ned Kelly’s Sympathisers article, for example. We also have Thomas Curnow testifying that “every one in Glenrowan was extremely guarded except to their own immediate friends in speaking on the subject. I never spoke candidly to any one, except my own relations and immediate friends, about Kelly matters. I never spoke out my mind on the subject, and others acted in the same manner” (Q. 17603). We have numerous newspaper sources commenting on the fear with which the community was struck, especially in the period closely after the police murders. We have Hare in Last of the Bushrangers saying that people were unwilling to assist the police, or be thought to be assisting the police, for fear of their fences and crops being burned in revenge; then all the discussion of fear of reprisal against jurors given in evidence for the moving of Kelly’s trial from Beechworth to Melbourne, which I collected and posted to this blog last year, http://nedkellyunmasked.com/2020/08/why-was-ned-kellys-trial-moved-from-beechworth-to-melbourne/

So I offer the following answers to your two opening questions:

To the question about McQuilton’s work, whether the hardship facing the selectors, at that time, translated into support or sympathy for Kelly, the answer is no, the two things are wholly unconnected. Morrissey’s PhD thesis was directly a critique of McQuilton’s PhD thesis as republished apparently with little change as The Kelly Outbreak. Two impressive pieces of PhD work. Whatever hardships selectors faced –which was not so much as we are commonly asked to believe, given the overall success they experienced, as Morrissey demonstrated – it had nothing whatsoever to do with generating any sympathy for the outlaws. I tackled this myself in my Republic Myth book.

To the second question, for Morrissey, whether there was a claimed widespread fear of the Kellys which would explain the inability of the police to catch the Gang, I see it as more complex: a widespread fear of the gang and associates which as David pointed out ensured that people minded their own business and avoided being seen assisting the police was one but only one factor as to why it took two years to catch the gang. The main reason is the fastnesses (as they called them then) of the wild and rugged north east terrain which made pursuit extraordinarily difficult. It is one of the main things talked about in the papers back then, and in much commentary since.

You are right that Morrissey read Ellis; his book is in Morrissey’s PhD thesis bibliography. Your quotation from Ellis, of the people of Greta, that “People in the neighbourhood showed no fear of being molested and went about their duties during daylight and darkness,” demonstrates only that those who went about their business and kept their mouths shut had no problems. But the Kelly gang and their extensive clan of relatives and criminal associates, and the trouble they caused, ranged far wider than Greta. Mansfield was a panicked town after the police murders, for example, with the notorious Wright brothers (as one example) hardly calming influences on citizen’s nerves.

Hi Perc, your post pretty well exactly reflects what I thought reading through Doug Morrissey’s books. Have you read his 2015 “Ned Kelly ‘A Lawless Life” in here he makes out Kelly sympathizers do better on the land than non sympathizers.

Perc suggests that in Scott’s ‘Edmund’s Song’ (https://www.bartleby.com/337/953.html), “The brigands and rapparees were lionised and protected by the peasantry – much as Hobsbawm observes elsewhere, and much as McQuilton suggests may also have occurred in the North East.”

Hobsbawm was a 1950s Marxist social theorist whose claim to see social bandits as folk heroes to peasant communities has been rigorously critiqued as a politicised theoretical hypothesis for which evidence is almost entirely absent. See Richard Slatter, “Eric J. Hobsbawm’s Social Bandit: A Critique and Revision” (North Carolina State University). Slatter defined banditry as taking property by force or the threat of force, often by a group, usually of men. Whose property? Often the peasants… I give some extracts from Slatter below:

“In 1959 Eric J. Hobsbawm created one of the most famous and influential historical archetypes, the social bandit. Fleshed out a decade later in his book Bandits, the construct touched off research on crime and social deviance around the world. Hobsbawm described “social bandits” who gained fame, Robin Hood reputations, and popular adulation. These men made themselves admired by flaunting authority and championing the interests of the folk masses against elite oppression. In exchange, peasants admired, protected and aided them. Other writers have broadened and applied Hobsbawm’s model, for example, creating similar pirate heroes out of Edward Teach (“Blackbeard”) and other corsairs.

“Hobsbawm based his interpretation primarily on fictional literature (often elite lore) and printed sources inspired by folklore. Elite lore reflects mostly a writer’s imagination and the reading public’s taste for blood and gore. Much bandit mythology emanates from literate, urban, middle-class writers with no first-hand experience of bandit-folk ties, real or imagined. The power and allure of these images come in part from a seeming need for even highly urbanized societies to retreat to a “sometimes heroic past.” Popular culture reveals little of the social reality of bandit behavior.

“By the late 1970s, scholars had examined official Latin American police, legislative, and judicial archives for clues to the behavior of the bandits so forcefully evoked by Hobsbawm. Based on archival evidence, researchers, including Peter Singelmann, Linda Lewin, Bill Chandler, Paul J. Vanderwood, Richard W. Slatta, and Rosalie Schwartz, revised, refuted, and emended the social bandit model. The flesh-and-blood bandits that they turned up in Latin America simply did not fit.

“Researchers working across the globe — Corsica, China, Greece, Malaysia, Italy, and elsewhere–likewise found few historical figures to match Hobsbawm’s model. Critics include Anton Blok, Pat O’Malley, Richard White, Donald Crummey, Phil Billingsley, Stephen Wilson, and Boon Kheng Cheah. Printed sources about bandits often project the urban bourgeois views of writers who romanticized peasant oral traditions for their own literary and political reasons.

“If the literary and folkloric sources that Hobsbawm used are often flawed, what of documents found in official government archives? … Official reports, minutes, confidential correspondence, telegrams, court records, and contemporary press accounts can be used to good advantage. … Given the extensive research into other than literary sources, why have researchers turned up such meager archival evidence to support Hobsbawm’s social bandit model? Owing to his reliance on folkloric and literary sources, he exaggerated the tie between peasant and bandit that “makes social banditry interesting and significant. It is this special relation between peasant and bandit which makes banditry ‘social.’” Other bandit attributes may be disputed or open to various interpretations, but the existence of this relationship is essential to the model’s credibility. … Researchers for Latin America and other regions of the world have found this “special relation” largely absent or mythical.”

In sum, it seems that real world attempts to find peasants admiring bandits almost invariably discovers them suffering under them much in the style of Kuroswa’s ‘Seven Samurai’. Morrissey is right: the social bandit model doesn’t work in Australia. And Slatter summarises much other work to show it doesn’t work elsewhere. It is another example of a Marxist social theorist pushing a revolutionary barrow from the comfort of academia. One needs to take a lot of academic writing with a large grain of salt.

Hi Stuart. I read Hobsbawm’s Bandits forty years ago and quite enjoyed it. I imagine I still would. I wasn’t interested in bandits as proto-revolutionaries or primitive class agitators, in the same way that McQuilton’s tentative suggestion that the North East might have been on the brink of rebellion doesn’t ring true to me either. Nevertheless, both Hobsbawm and McQuilton say a lot that does ring true, I think.

When reading Hobsbawm I guess I was thinking of an Irish Catholic peasant in the early 1800s, for example. As for all Catholics, it had been unlawful for him to attend school, he was not allowed to own land, his livelihood depended entirely upon the whim of his absentee English landlord, and he was forced to pay a tithe to his landlord’s church, among many other restrictions. If a neighbour attacked the landlord’s bailiff, as often happened, I can imagine that man being understanding, and supportive. And Irish songs of rebellion, written by those who were lucky enough to be able to write, reflected believable sentiments, and given the substantive evidence, did not manufacture them.

If that man’s sons and daughters, having endured the Famine and England’s neglect of Irish suffering, had fled to Australia, I can imagine them being less than committed to an English authority which had outlawed, however justifiably, four local boys – three sons of Irish convicts, and the grandson of an Irish convict. I can imagine that the Kearney’s, the Egans, the Delaneys, the Tanners, the McAuliffes, and many many more such people, being were quite conflicted – torn between a desire for a more hopeful future in this British colony and their inherited contempt of the English.

Its interesting that Ellis, son of an Irishman, prominent local Protestant, committed Christian, certainly no member of the Greta Mob in his youth, seems to be similarly conflicted, and struggling to reconcile his belief in law and order with his sympathy for the Kellys.

“Edmund’s Song” was written by a literate, urban, middle-class writer with no first-hand experience of banditry, as Slatter would point out, and who quite unrealistically romanticises brigandry. But by using it in his History of Greta Ellis is effectively lionising and mythologising Kelly. And the question is to what extent this local literate former school teacher was reflecting the views of a broader otherwise silent group of people. He certainly is no left-wing armchair academic sprouting ideas he has not lived.

I’ll upload the pages four pages of Ellis’ book, and be interested in your views. I’ll put up my notes on Jacob Wilson too. Maybe someone would be interested.

IMG_20210531_0001.jpg

IMG_20210531_0002.jpg

IMG_20210531_0003.jpg

Perc you will have to upload those images again by selecting the “Choose File” button at left.

S.E.Ellis A History of Greta pp 32,33

Attachment

S.E.Ellis A History of Greta pp.30,31

Attachment

S.E.Ellis A History of Greta pp32, 33 (image one should be pp 28,29!)

Attachment

Hi Perc, many thanks for uploading, now we are all on the same page (excuse bad pun). Will get back to you here.

Hi Perc, first, I am most grateful to you for putting Ellis’s pages up for review, but I have some serious difficulties with the content, as I do with Hobsbawm. Hobsbawm won his reputation as a theorist from his Bandits book; and while doubtless interesting that does not mean correct. Much more interesting in my view is legendary Marxist academic G.E.M. De St.Croix’s “Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World”, over 60 pages of densely footnoted tripe in which he combs ancient history for evidence of class struggle. Both professorial Poms, of course. Another port, dear chap?

Now to Ellis. By the NLA catalogue Ellis lived 1873-1942, so was 5 to 6 years old during the Kelly outbreak, and wrote his book circa 1940, some 50 to 60 years after the Kelly outbreak ended (https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1918087). It was republished in 1972.

Ellis is obviously wrong to claim p. 29 that news of the Kellys doings while they were outlawed “mostly originated from the police station at Greta”; most of it came from Benalla or Wang district offices, or Melbourne central, never Greta; although it is true that “they had many opportunities of ambushing the police had they so wished.” He could not know as the police files were not accessible then that there was at least one other derailment attempt envisaged with kegs of gunpowder found, and he suggests against the historical record that claims of the police avoiding the outlaws were rare. In most cases the search parties were keen to catch them both before and especially after SBC.

Ellis gets the SBC story wildly wrong by having the gang sneak up on the police camp at breakfast time, and Byrne stealing the sole policeman present’s rifle, who then shouted a warning to the other three police who came quickly and started firing at the gang, i.e. a proper gunfight, with three police being killed and one getting away. All of this is laughably inaccurate, and Ellis has clearly not looked at any old newspaper or other widely known published accounts such as White’s or Boxall’s or Chomley’s books, and seems not even familiar with Kenneally’s version. He says absurdly, “The four bushrangers afterwards placed the bodies in the tent” (30). No version anywhere has that; the bodies were left where they fell. Ellis is just repeating some old stories from somewhere without any checking at all.

Ellis then relates the story of the police avoiding an encounter with the gang by turning back after having their proximity pointed out by a native tracker; that discredit belongs to one policeman in charge on one occasion, not the force generally or even all in that group. Ellis then gives the version of Glenrowan that the aim was to capture some senior police and hold them hostage until pardoned, a tale that others including Sidney Nolan thought plausible but was always errant nonsense.

Ellis then claims (31) that “Individuals were immune to their attentions, except when they required a good horse of a fat heifer”. That was in fact where most of their attention went; stealing the plough horses of poor selectors and the stock of passing drovers, preying on the poor far more than they ever did on a few squatters. He says, “People of the neighbourhood [Greta] showed no fear of being molested, and went about their duties in daylight or in darkness.” What choice did they have? As discussed in a previous post, they kept their mouths shut, and Ellis has no memory of the pervasive fear that kept them that way writing some 50+ years after the events that took place while he was barely 6 years old. Evan in Kenneally’s day, Kenneally could write that anyone criticising the Kellys in the district would likely end up in the Wangaratta hospital (Inner History, 1980:16). As above, Ellis has done no research to correct his facts, and is not even good for generalisations. “Great was the astonishment and wonder of some Greta farmers, on going to their paddocks one autumn morning, to find the mould board had been removed from their ploughs.” No, it happened over a period of time, and yes, their livelihoods were thrown into upheaval by their ploughs being rendered unusable by the plundering varmints until replaced. The Kelly gang didn’t give a toss about poor selectors.

Ellis is yet another who claims inside knowledge of who made the armour to enhance his credibility – “I need not supply his name” – but all he could have is some old rumour, of which there were many, and which he thinks his is credible. He says, “The Kellys did not kill for the sake of killing.” There is no question that they killed Kennedy for the sake of killing, as McIntyre had fled, and they then turned two murders into three. Ellis writes (32-32), “It was wild and new country, and adventurers from distant lands had not yet realised that law was the foundation of freedom, though it be sometimes harsh and unequal.” What planet is this guy from? The place was settled under law from the get-go; that’s why it was dotted with police stations and a court system. Ellis ends with platitudes about the Kelly being not always blameless, and says they were not always guilty when punishment was meted out to them. In fact, as David has shown in a series of posts on this blog, they and their criminal clan were guilty of far more than they were ever convicted for, and given the benefit of the doubt by the courts on multiple occasions against police witnesses.

Of the lines from Scott’s “Edmund” referencing Greta, Ellis says the original 1842 Greta run on the 15 Mile was probably named after Yorkshire’s Greta River and that in the poem the banks of that river an old disused quarry or cave was the home of a band of outlaws, “The coincidence of which seems almost prophetic”. This is exactly the kind of mythmaking from literature that Hobsbawm turned into a social bandit theory as I summarised from Richard Slatter, pure romantic nonsense. Worse, Ellis started his Kelly chapter directly stating that it is untrue that Greta is the “Kelly country” as “The Kellys never lived in Greta but over the hills to the westward, close to the road leading to Benalla”. In other words, his own rebuttal of the association destroys his fanciful romantic parallel. So one can’t see his quotation from Scott as lionising and mythologising Kelly; rather it is just what he says it is: an “almost prophetic” word association of wholly unconnected material linked only in his imagination.

The good thing about McQuilton’s Kelly Outbreak book is that he works methodically and collects the evidence for each section in its place. That means you can be pretty confident that he has covered his source material for any section well, and put it up for inspection with proper referencing, unlike many others including Molony who cherry picked many of his sources references, often not presenting the full picture, though not as bad as you know who.

One might reasonably ask whether “the Kearney’s, the Egans, the Delaneys, the Tanners, the McAuliffes, and many many more such people [of Irish descent], were quite conflicted – torn between a desire for a more hopeful future in this British colony and their inherited contempt of the English”, but the sons of these families who were Greta Mob types had contempt for normal citizens generally – Morrissey says their term for them was “mugs”, but gave no reference – and not divided on historical national lines; they would prey on anyone. The emphasis on Kelly’s Irishness was an Ian Jones invention dating back to 1968 Man & Myth talk; the key to Kelly in Jones’ view; but this is nonsense too. Kelly consistently described himself as freeborn colonial, a native, not Irish. There is not much about Irishness in the Euroa (Cameron) letter; that’s one reason why Jones focuses on the later Jerilderie letter; but that is just a longer and flowerier version of the same list of whining complaints. There is nothing remotely connected with Irish rebellion an any of his reported rants during his hold ups, or in his various court appearances, or his condemned cell correspondence.

From your summary of Ellis as the son of an Irishman, prominent local Protestant, committed Christian and local literate former school teacher I think we can see the literary interest via Scott in this case; but we can see the common habit of quoting bits of poets including Shakespeare in books and newspapers right through the latter half of the nineteenth and into the 20th century. I would put Ellis in the same basket as Joseph Ashmead’s 1922 “The Thorns and the Briars”; a committed Christian’s ramble about the Kellys that is for the most part historically ignorant. The Kelly gang stand out for the horror of their crimes – Ellis finds it hard to contemplate that the gang really wanted to slaughter the police train, “to kill and awe the police” (31), and so he resists the necessary conclusion of righteous anger that such a crime should invite. He was a little boy when it happened, and now in the 1940s with no research he prattles and opines like many another schoolteacher about things he actually knows nothing about. Such is life.

Sorry, DeSt.Croix is over 600 pages, not 60 pages! And he even has an appendix that he first published elsewhere anonymously poking fun at some of the ridiculousness of his own work. All fun and games in well paid academia…

OMG Stuart, even I feel thoroughly chastised after reading that response! But sadly you have hit – or maybe I should say smashed – the nail on the head : this is yet another author who tries to rewrite history, and rehabilitate the image of the Kelly Gang as romantic and dashing underdogs boldly taking on the oppressive authorities.Why should anything they propose be given credit when ordinary available facts are ignored or misrepresented?

I must admit to not having registered that comment from Kenneally that anyone criticising the Kellys would likely end up in Wangaratta hospital! One thing I would like to see better referenced are the claims that selector stock was targeted by the Gang. This obviously exposes the myth of the Gang being the friend of the poor and the ‘downtrodden’, as also does the theft of their mouldboards.

I also must admit to having never really been convinced by the line the myth makers push about the Kellys links to the Irish republican struggles back home. Its undeniable they were horribly oppressed and maltreated, and the famines were shocking and devastating but as you say Kelly himself didnt really refer to all that except perhaps as an excuse to gain sympathy or as some kind of justification when it suited him.

I hope Perc wont be too upset by your critique and I look forward to his response. It was good of him to post those pages, I just hope he isnt regretting it now!

HI Stuart,

I can agree with everything you say. My critique of Ellis would be identical to yours. You state the bleeding obvious, at great length! But you get yourself so agitated by his historical inaccuracies, that you overlook the bleedingly obvious question: what does it say about the local community that a local prominent Christian, like Ashmead too, feels the need to paint Kelly in such a favourable light, mythologise him in fact, and completely make light of his criminality. You don’t seem to be able to consider that question. I’ll leave it with you.

Pfff, grow up David. Not upset at all – agree with everything he says. I was just hoping that he might consider the wood, having missed it for the trees

Perc you ask “what does it say about the local community that a local prominent Christian, like Ashmead too, feels the need to paint Kelly in such a favourable light, mythologise him in fact, and completely make light of his criminality?.”

Well, I have no idea what the answer to your question is – only Ellis could answer that. But what I can say is that it has to have been drawn from what he believed to be true about the Gang, and much of what he believed was of the standard sympathiser view of the outbreak as a confrontation between an heroic Kelly versus the oppressive police. Heres an example from top of page 30 which pointedly depicts the Kellys as underdogs and the Police as ruthless:

“In a few minutes the other police were on the spot. Dismounting and taking cover behind their horses they opened fire on the Kellys. The latter, from the shelter of logs and trees though possessing only shotguns returned fire and killed three of them including their leader – Sergeant Kennedy”

So it would seem Ellis believed the police opened fire on the gang because Joe Byrne had crept up and taken McIntyres rifle. Obviously that would have been a massive over-reaction , shooting to kill men armed “only” with shotguns and anyone believing that to have been what really happened would understandably take the side of the Kellys. But that is very much NOT what happened. Its a completely wrong description of the ambush, it ignores the events leading up to it, it makes no mention of the Kellys career as major criminals in the district, it doesnt record the tracking down of the wounded Kennedy and killing him in cold blood half a mile away, or the fact that it was four gang members against two on two seperate confrontations.

So, over to you : why do YOU think Ellis painted Kelly in such a favourable light? Could it have had anything to do with his completely abysmal grasp of the facts – what you call the trees ?

You keep on about his obviously incorrect claims, David. We agree entirely; its hopeless history. Almost entirely inaccurate.

So the question is how did he come to view the Kellys in this way? He wasn’t writing to make a sensationalist dollar, or a name for himself. He was writing for his local community. He wasn’t in the Greta Mob, he wasn’t one of Morrissey’s bad people. He was every bit one of the “good’ people. And he hadn’t read Ian Jones.

But he grew up with the Outbreak happening around him – he was 5,6,7 – pretty sensitive to the adult world. He says none of them were frightened. He attended Church every week, and knew that thieving and killing were sins, yet he chooses to make light of those matters. He should be saying, like you, that Kelly was a lying, thieving monster. But he doesn’t. He makes excuses, he smoothes over unpleasant realities. He sympathises with Kelly and effectively mythologises him. You don’t find that odd? And all you can say is you don’t know why he did that. Or, as Stuart says, they are the prattles of a half-wit schoolteacher. That isn’t any attempt to think critically.

One explanation of Ellis’ opinions is that he was reflecting his communities view. Not the view just of the Greta Mob, but the view of the christian community of which he was a prominent member. You can shrug your shoulders and say you have no idea why Ellis believed what he did, but if you are fair-dinkum about dealing with the facts, then you need to deal with the fact that Ellis wrote what he did, and not keeping banging on about how wrong he was. He’s quite wrong, I get it. But seemingly he is reflecting a community view, and is in fact struggling to accomodate that view with his other responsibilities to law and order, not to mention his christian commandments. I’d suggest that Ellis’ book indicates that the Greta community wasn’t made up simply of Morrissey’s very good people vs. very bad people, and that many good people were conflicted by feelings of sympathy for Kelly. I’m sure you won’t agree, but simply brushing Ellis off doesn’t indicate any real interest in what might be a truth.

So, if you like, over to you! Don’t shrug your shoulders. Explain how you see it.

Perc let me put it this way:do you think Ellis would be having such a struggle if he was correctly informed about the Outbreak?

We do at least agree that he wasn’t in the least bit correctly informed but you don’t seem to think that has any relevance to his analysis whereas I do. I don’t think a credible analysis can arise out of such an inaccurate understanding of the facts.

In as much as the community shared his view – and I do accept your claim that like Ellis others did genuinely have some sort of conflicted sympathy for the gang – I would argue that also like Ellis’s, it emerged from ignorance of the facts. However I believe such people were very much a minority, going by what was written in the newspapers of the time.

If correctly informed he may well have had a different view, that is something we genuinely can’t know, David. But its not the point, is it? He did have that view, and it is likely that it was a view shared in the community, which suggests there was some reason for them to recognise something in Kelly that allowed them to virtually ignore murder and theft. Ellis is not a fool, in spite of Stuart’s opinion of schoolteachers. He may not have known the exact details, but he knew Kelly had killed, the armour must have been a hint for him to realise Glenrowan was to be a serious assault on the police. He clearly defends Kelly.

We are not analysing his facts, we’re seeking the explanation for him holding those facts in the face of evidence he must have had before him and which suggested Kelly was someone who should have horrified him.

Ellis could read, after all. He would have been well aware of the position taken by newspapers on Kelly, and of the details they presented about Stringybark, and Glenrowan. And he chooses to deny them.

At the risk of sending Stuart into another apoplectic dismissal of Hawbsbawm – again, quite justified in part – Ellis’ view strikes a chord in my mind with Hobsbawm’s explanation of the rural criminal transformed, in certain circumstances, into a legendary folkloric hero. That seems to me is exactly the transformation Ellis reflects. And it didn’t happened because of Ian Jones et al., it was happening well before that. (And before anyone gets upset, I’m not suggesting at all that Hobsbawm’s armchair theorising is directly transferable to the N.E in 1878 – but he has some interesting ideas.)

We’ll never know how many locals backed Kelly, and to what extent, in the same way we’ll never know how many feared him, and to what degree. But both are likely to be the reality, and Morrissey’s obfuscation of Wilson’s situation, and his ignoring of Wilson’s neighbour Ellis doesn’t lead to a fair understanding of what might have been going on back then.

Perc, you keep asking WHY Ellis, and others in his community had the beliefs they did about Kelly, and more than once have suggested they must have ‘recognised something’ in him that caused them to have the beliefs they did.

I would have thought – and said so before – that what they believed to be true about the kelly story IS the explanation for those beliefs about Kelly. I don’t see a need to go looking for some OTHER explanation than the one that is true for all of us who try to think rationally, that our explanations for things emerge out of our understanding of what we think are the relevant facts. To me, it makes sense for Ellis to be sympathetic to Kelly because, though as a christian he no doubt believed the killings were wrong, he also believed in forgiveness, he also believed that only ‘he who is without sin’ should cast the first stone, and he also believed those killings were committed in self defence after police opened fire on the Kellys who were armed ‘only’ with shotguns, for trying to steal a rifle. And so on….

So what did they recognise in Ned Kelly? I think they thought they saw a victim of police harassment and persecution who exercised his right to object to it. That is why misinformed people today STILL have sympathy for the Kellys.

Hi David, that lines up very well with what two other evangelising Christian writers have said. The first is Rev John Singleton’s “A narrative of incidents in the eventful life of a physician”, 1891, who ministered to Kelly in the Melbourne Gaol until he was stopped by the Catholic priest. The other is Kerry Medway in his short modern book, “Is Ned Kelly in heaven?”. Both seem convinced that Ned repented and could have joined the saved. Pity about the victims, but. Kelly boasted he would send the police to hell.

I have two neighborly co incidental stories to do with the Kellys. One was in 1985, I was showing my neighbors* some of the bullet lead I had detected at Kellys Ck, I excitedly told Mr and Mrs Frank and Francie Douglas how I had found the Kelly hid out. Francie was not too excited about Kelly things as she told me she was a (nee Ellis), and her Grandparents family had settled in ‘Boho’ some 14 miles SW of Benalla. Old Francie told me, her Ellis family as kids were playing way out near the back fence of their farm when four men came out of the bush, jumped the fence and wanting water, they went straight to the house and filled their water bottles and took off again. As Francie told me, the little girls were terrified of the strangers as this was a most unusual thing – they were the Kelly gang.

If S.E.Ellis was born in 1873, it is possible he was one of the kids with his sisters that encountered the Kelly gang visit to their house.

Hi Perc, the trees do get in the way sometimes but as the line in Macbeth goes, “Macbeth shall never vanquished be, until Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill shall come against him” (4: 1:. 105,) so perhaps there is a little clearing through which that great movement can be seen. There are two initial points:

First, I must say my view of schoolteachers is not all one-sided. Where would we be without Mr Elliott’s brilliant history of the Jerilderie bank robbery, or Mr Curnow’s bravery, testimony, and sterling reputation as an educator? One of my mates is an economics teacher. It’s more the last 30 years of humanities dribble-brains that crack me up. Nineteenth-century teachers were a class above twentieth century ones; Australian literacy was much higher in the last decade of the nineteenth century than in the 20th.

Second, Perc says that “Ellis’ view strikes a chord with Hobsbawm’s explanation of the rural criminal transformed, in certain circumstances, into a legendary folkloric hero. That seems to me is exactly the transformation Ellis reflects.” I already said that, that this is exactly the kind of mythmaking from literature that Hobsbawm turned into a social bandit theory which I summarised from Richard Slatter, and is pure romantic nonsense. Perhaps what we disagree about is the extent to which one can get anything useful out of Hobsbawm, in which case each to their own. For me it is transparently Marxist baloney, a theory in search of evidence which it failed to find to any extent worth mentioning. Others however have noted his massive influence in academia, and they can’t all be Marxists, can they? University sociology course still start with Marx, Weber and Durkheim, and so get the base of twentieth century society totally wrong. Then they flit to contemporary cultural Marxism, where their connection with reality is all but totally lost and they are fit only for careers in academia, teaching and the woke public service. But not everyday commerce and industry.

Third, David asked for a reference for claims that selector stock was targeted by the Gang. The best short article on that is probably Morrissey, “Ned Kelly and Horse and Cattle Stealing”. Victorian Historical Journal 66.1 (June, 1995), 148-155.

Back to Ellis, Perc’s central contention seems to be that from within Greta a local prominent Christian writing for his community circa 1940 painted Kelly in a favourable light and made light of his criminality, although he knew that thieving and killing were sins. Perc says Ellis “grew up with the Outbreak happening around him – he was 5,6,7 – pretty sensitive to the adult world,” and that regardless of its historical accuracy Ellis “did have that view [of some sympathy for Kelly], and it is likely that it was a view shared in the community, which suggests there was some reason for them to recognise something in Kelly that allowed them to virtually ignore murder and theft.” He suggests that one explanation for Ellis’s is that Ellis was reflecting his communities view, and that many good people were conflicted by feelings of sympathy for Kelly.

I think the key to this is that it’s only an assumption that Ellis at the age of 5 to 7 had much understanding or later memory of what happened during the outbreak. We have seen endless examples of people trying to link themselves in one way or another with the famous outbreak, and I gave a number of these in the republic Myth book. We could add Ellis’s belief that he knew the secret of who made the armour to that. The world moved on between 1880 and the last 1930s or 1940 when Ellis penned his local history. He grew up with the Kelly days a decade old before his youth, and an old memory with the Boer War and WW1 in between then and his historically inaccurate memoir. In the meantime Kenneally’s 1928 (serialised) and 1929 (book) history had done much to change the view of Kelly – even though it appears Ellis hadn’t read it, as he takes a much different angle.

By 1930, it was clear to one writer that “Kelly and his picturesque ruffians are gradually acquiring the rosy glow of heroes of romance. How Ned and Dan Kelly and their accomplices [Byrne and Hart] appeared to their contemporaries, how much terror and hatred they inspired, and with what exultation the community heard of the destruction of ‘those pests to society, the Kelly gang’, is shewn in the official telegrams [of the day]. … As an antidote to the hero myth which is rapidly enveloping the Kellys they are invaluable” (Argus, 30 June 1880, 6).

So I think what we have here is Ellis reflecting a changed view of Kelly that came into play in the 1930s including through his community but had little basis in historical fact even in his own early life. David is right there. By the 1940s Kelly had become something of a folk hero to some; but was not in his own day. Hobsbawm doesn’t fit because amongst other things Kelly would have had to be seen as a bandit hero between 1878 and 1880 when he was alive, not in the 1930s or 40s or later. We don’t see that. We see a community outraged by the attempt on Constable Fitzpatrick’s life. We see a community plundered and pestered by a gang of stock thieves and their rowdy Greta Mob mates. We see a community horrified by the SBC murders. We don’t see any folk hero worship at all except in some larrikin ballads sung to stir up the police; if that’s what a folk hero is. But that’s not what Hobsbawm meant at all.

And Bill, that’s a great story about the Kelly gang filling their water bottles at a farm with the little girls afraid of them due to their reputation; another oral example of the fact that ordinary people were afraid of them.

Oops, my reference for that 1930’s quote was wrong. I accidentally copied and pasted an 1880 source reference from a different note in my Republic Myth book. Gong! The relevant paragraph above is,

By 1930, it was clear to one writer that “Kelly and his picturesque ruffians are gradually acquiring the rosy glow of heroes of romance. How Ned and Dan Kelly and their accomplices [Byrne and Hart] appeared to their contemporaries, how much terror and hatred they inspired, and with what exultation the community heard of the destruction of ‘those pests to society, the Kelly gang’, is shewn in the official telegrams [of the day]. … As an antidote to the hero myth which is rapidly enveloping the Kellys they are invaluable.”

The correct reference is Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser, 8 January 1932, 2.

In his bibliography, Kellyana, (Melbourne: Hawthorn, 1943), Clive Turnbull held that Kenneally’s was ‘the most complete account of the Gangs’ doings’, and noted that there was also ‘a consistent demand for Dr. W.H. Fitchett’s account’ [Ned Kelly and his Gang, first published in his 1913 New Worlds of the South], p. 1. Fitchett’s is a short, vivid, ‘Boys’ Own’ style booklet that ends with statements by Sgt. Steel and ex-Sgt, O’Dwyer, who captured Kelly.

There is no evidence anywhere that Ned Kelly was involved in any kind of campaign to “liberate” anything, except bullocks from bullockys (Susan Scott letter), draft horses from other small selectors (Inspector Hare in RC; Doug Morrissey), other horses from anywhere not nailed down (passim), watches from corpses (SBC) or hostages (Euroa) at gunpoint, money from travellers (Ah Fook), and money from banks. In addition, he stuck up numerous persons at gunpoint, then fatally shot Metcalf while “fiddling” with a revolver.

So a Boho Ellis recollects fear of the Kellys, when a little girl, and this is an indicator of the ordinary person’s fear of the Kellys. But a Greta Ellis recollects no fear of the Kellys, when a little boy, and this is simply “the prattles and opines, like many another schoolteacher, of things he actually knows nothing about.”

Hi Perc, you got me there… or did you? The Greta Ellis published a local history, which is the topic here, in which he generalised about the feelings of Gretans. Whereas Bill has relayed a story from a Boho Ellis which I found interesting but give no particular evidentiary weight to. As they are both Ellis’s, maybe one cancels the other out? Or maybe the Boho Ellis story shows that the Greta Ellis story is an invalid generalisation…

Hi Stuart, I was really pointing out a sad need to smear and belittle.

That’s very sad, I’m sorry to hear that.

Hi Perc, I think you have missed the point. Within the same broad family tree, someone one in Greta holds that most people around Greta sympathised with the Kellys to some extent. Somewhere else in the family branch there is a view that contradicts that from their own lived experience when they were kids. But what is the timeline? It seems they are both talking about childhood memories but one is writing around 1940 for readers in his own day whose recollections of events some 60 years ago have been coloured by time (and we should expect romanticised) as regards the Kellys by 1930 if not before. The Greta Ellis holds that people went about their business by night and day without fear in the Kelly days; whereas the Boho Ellis is an instance of being afraid of the gang. I think David said first that if people minded their own business and didn’t talk badly of the Kellys or talk to the police they had little to fear. The references I gave for Curnow and Kenneally back that up. The point is that the Boho Ellis story shows that the Greta Ellis story is an invalid generalisation.

I think Stuart has been too harsh in his criticisms of Ellis’s little book. It is just a delightful collection of reminiscences which he assembled as I understand it for the benefit of fellow residents of Greta. The Kelly story was just one small chapter.