Here’s the outcome of another meticulously researched and argued investigation by Dr Stuart Dawson, which like all his others, corrects mistaken claims that have been part of the Kelly mythology for generations. This one is for people with a genuine interest in discovering and understanding the mechanics of colonial outlawry, which rules out most Kelly sympathisers, who boast about Kelly books they own but have never read! For the few who care, it’s a read that requires close concentration but its such a pleasure to follow a genuine academic argument, to trace the links back and forth across the history of crime and intellectual argument about enforcing the Law.

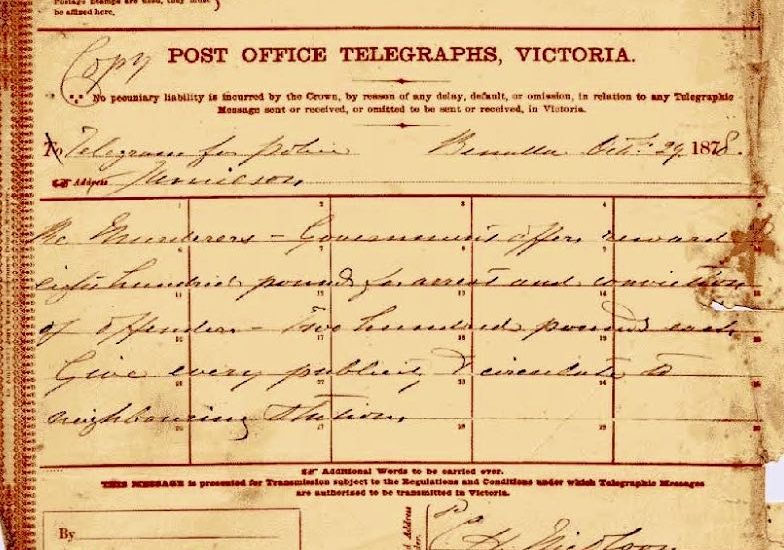

A new article by Stuart Dawson just published in the journal of the Australian and New Zealand Law and History Society examines the origins of the Felons Apprehension Act under which the Kelly gang were outlawed after their murder of three police at Stringybark Creek on 26 October 1878. The murders were huge news: just three days later, on 29 October, a telegram (shown above) advises

“Re Murderers

– Government offers reward of eight hundred pounds for arrest and conviction of offenders – Two hundred pounds each. Give every publicity, and circulate to neighbouring stations.

C. H. Nicolson Inspecting Supt.”

An overview history of pre-colonial outlawry is provided in the article. There was a great difference between outlawry under the Australian colonial outlawry Acts which sought a felon for trial, and outlawry for a capital crime under the common law of England which amounted to conviction. Understanding this difference is crucial to understanding why – despite a widespread belief to the contrary – an Australian outlaw could not simply be shot on sight by anyone with no accountability or repercussions.

Outlawry was a process applied to a person wanted for a capital felony, and who failed to surrender to appear at court when called to do so. A potential outlaw had to be given the chance to surrender on pain of outlawry, and notices had to be placed in newspapers as well as in the Government Gazette to notify the wanted person that he was required to surrender himself by a certain date. Failure to do so under that systematic legal process led to outlawry.

The first colonial outlawry Act was the New South Wales Felons Apprehension Act 1865, introduced in response to a prolonged epidemic of bushranging. It provided that after due proclamation of outlawry, “the outlaw may at any time – either by a constable or a private individual, and either with or without demand to surrender – provided he be armed or reasonably suspected of being armed, be shot dead”. This drastic power contrasted with the common law which required that in the apprehension of wanted felons, no more than reasonable force could be used. This was traditionally interpreted as requiring a warning or challenge before the use of lethal force.

In a speech in April 1865, some two weeks after the passage of the NSW outlawry Act, NSW Chief Justice Alfred Stephen – who largely drafted it – said, “it is too much to expect that persons encountering armed ruffians like these should, in addition to the risk of being themselves instantly killed, incur the danger of a charge of felony [i.e. of murder] for an act righteously meant – but perhaps not in strictness legally justifiable. The most humane will hardly contend, that … a proclaimed and armed felon of that stamp, who has set all law at defiance, may be allowed one more chance of his life, and of escape, by requiring a challenge”.

To Stephen CJ, the Felons Apprehension Act 1865 (NSW) was “a measure as just and (in the true sense of the word) merciful in its provisions, as these are likely to be beneficial to the community”, and “entirely … in accordance with the principles of our ancient English law”.

But crucially, as he made clear, “It is evidently not meant by this, that the outlaw is needlessly and wantonly to be killed; for the words are, ‘may be taken alive or dead’”. The Act is more “careful of the accused’s safety” than is English law: he does not stand already convicted of the charge for which he is outlawed; he has “ample means of knowledge” with time to surrender before outlawry; and “if he be not armed, and so may be approached without danger to the taker’s life, the colonial outlaw is (as to apprehension) on the footing of any other indicted person”. The intent of the NSW Act absolutely rejected the “barbarity” of the law of England when an outlaw “might be killed by anyone … without pretence of the furtherance of justice”. It became law on 8 April 1865.

Later, in the colony of Victoria, following calls for urgent action against Ned and Dan Kelly and their two as yet unidentified accomplices for the Stringybark Creek police murders of 26 October 1878, widespread consternation led to demands for those involved in to be outlawed by a process similar to that used earlier in New South Wales. The press of the day typically approved of the Victorian Act, and it is clear from its title and preamble that its intent was “to facilitate the taking or apprehending of persons … and the punishment of those by whom they are harboured”, not to outlaw them for summary execution. The Felons Apprehension Bill was rushed through the Parliament and became law on 1 November 1878.

Kelly historians have almost universally taken section 3 of the Victorian Act, which provided for the apprehension or taking of an outlaw “alive or dead”, as a blanket licence to kill an outlaw on sight without any qualifying criteria. This mistaken view results from a cursory reading of the Act and from excessive reliance on newspaper diatribes and emotive speeches in support of it. In fact, just as in the almost identical NSW Act from which it was adapted, the expression “alive or dead” showed that the aim was justice by trial if possible, not summary execution. As Charles Duffy MLA asked in debating the Victorian outlawry Bill in the Parliament, “What would the civilized world think if a law was passed condemning the men to be shot unheard?”

Under the Act’s provisions, an outlaw could only be killed if he was found at large armed or reasonably believed to be so, as his apprehension would otherwise be impossible without a real risk of loss of life to the apprehender. Any person who killed a proclaimed outlaw outside of these clearly defined circumstances would have committed murder.

In the Kelly literature, section 5, the “harbouring” section, is the most controversial provision of the Victorian Act. Shortly after the enactment of the earlier 1865 New South Wales Act, NSW Chief Justice Stephen had said, “It has long been obvious … that the [bushrangers’ outrages] could not have continued unchecked … unless these men received extensive and ready assistance, by shelter and information, calculated to enable them to elude capture, and thus also to commit further crimes. [This] Bench, therefore, [recommended] enhancements of a comprehensive and more stringent character, against the harbourers and abettors of bushrangers; and to this, probably, in a greater or lesser degree, the late statute known as the Felons Apprehension Act is owing.” Similar concerns arose in Victoria, and a similar (but surprisingly, not quite as harsh) harbouring clause was put into the Victorian Act.

For Ian Jones, the harbouring clause was, “as J.J. Kenneally put it, ‘a declaration of war’”. It provided that if “any person shall voluntarily and knowingly” shelter or assist a proclaimed outlaw in any way, or give “to him or any of his accomplices information tending or with intent to facilitate the commission by him of further crime, or to enable him to escape from justice, or shall withhold information or give false information concerning such outlaw from or to any officer of police or constable in quest of such outlaw, the person so offending shall be guilty of felony”, and, if convicted, “shall be liable to imprisonment, with or without hard labour, for such period not exceeding 15 years”. No defence of compulsion would be valid, “unless he shall as soon as possible afterwards have gone before a justice of the peace or some officer of the police force” and given full information as to the circumstances. All this was intentionally a “very stringent provision”, and any who gave aid risked severe punishment.

In December 1878, senior police met to identify the core sympathisers in each of their districts for prosecution under the Act. As John McQuilton summarised it, “on 2 January 1879 warrants were sworn out and over 30 men arrested. Of these, 23 were detained in police custody. Some were released [within a few weeks, with nearly a third held for five to seven weeks], but a core group of [nine] men were remanded week after week” for almost three months.” Unlike the impression one gets from Jones, however, large numbers of sympathisers were not taken away from their farms and crops through the harvest season. The number locked up for any considerable time were few, and not all of them were farmers. Wild Wright, for example, was a labourer and career stock thief, not a selector whose crops were at risk.

Although the arrested sympathisers were charged, “that they did cause to be given … information tending to facilitate the commission by [the outlaws] of further crime, contrary to the Felons Apprehension Act 1878”, Crown prosecutor Bowman did not ask for a committal, merely a remand. In other words, the Crown did not press for trial, but was apparently content to prevent those who had been arrested as the most active sympathisers temporarily from aiding the Kelly gang. The police were undoubtedly also mindful of the example they were making for any other persons who might have been considering giving assistance to the gang.

At the time of its implementation the arrests had wide support across the community and press, but this dropped rapidly after a few weeks when court prosecution did not commence, and concerns about the justice of repeated remanding were raised in Melbourne as much as in the North-East. As Doug Morrissey emphasised, however, “the disquiet over remanding did not indicate support for the Kelly gang…. Rather, respectable people were disturbed at the flouting of the hallowed British principle of Habeas Corpus, which required that a person under arrest be brought promptly to court to face his or her accuser and that the case against them be produced”. That does not mean that the Act was ineffective.

Indeed, for all its controversy, the Felons Apprehension Act was a success. Information from the public increased over time. As then Royal Commission’s Second Progress Report put it, “At first the intelligence gleaned would be about a month old, then it was reduced to a fortnight, in time about a week, and sometimes a day only would elapse, before the receipt of news of the appearance of the gang, or the doings of their sympathizers”. In May 1880 Inspector Nicolson wrote, “the Queensland native trackers … and the precautions taken against a successful raid have baffled the outlaws. Their funds are almost exhausted, their prestige has failed considerably, and, consequently, the number of their admirers has decreased. … [T]heir few friends … are confined to their blood relations and a few chosen young men of the criminal class, who have known them from childhood. … [T]heir exhausted means compels them to expose themselves more and more to danger of betrayal and (or) capture”. Their spectacular downfall came a month later at Glenrowan.

There is much more to the article than this short summary. If you would like the full story – and who wouldn’t – grab the copy attached to this post and start reading. Do it now! If you wish to quote from it, the citation format is Stuart E. Dawson, ‘Ned Kelly Outlawed: The Victorian Felons Apprehension Act 1878’, law&history 8.1 (2021) 134-157. As copyright of articles in this journal is vested in the author, I cheerfully give permission for anyone to circulate it unaltered as widely as possible!

To get a free copy of this important piece of research click below:

Ned Kelly Outlawed – Dawson – corrected FINAL

‘Cuput gerat lupinurn’ [let his be a wolf’s head] — in these words the courts decreed outlawry.

Pollock and Maitland, History of English Law, volume 2, 449.

Attachment

Blurt.

What is an outlaw? Barry’s appraisal was true in Kelly’s own lived experience:

“Unfortunately, in a new community, where society is not bound together so closely as it should be, there is a class which disregards the consequences of crime and looks upon the perpetrators of these crimes as heroes. But these unfortunate, inconsiderate, ill-educated, ill-conducted, un-principled and ill-prompted youths must be taught to consider the value of human life. Such youths unfortunately abound, and unless they are made to consider the consequences of crime, they are led to imitate notorious felons, whom they regard as self-made heroes. It is right therefore that they should be asked to consider and reflect upon what the life of a felon is. A felon who has cut himself off from all decencies, all the affections, charities, and all the obligations of society is as helpless and degraded as a wild beast in the field. He has nowhere to lay his head, he has no-one to prepare for him the comforts of life, he suspects his friends, he dreads his enemies, he is in constant alarm lest his pursues should reach him, and his only hope Is that he might use his life in what he considers a glorious struggle for existence. That is the life of the outlaw or felon.”

And what do Kelly nuts make of it? Nothing. Picture attached.

Attachment