THE PINK GRANITE HOUSE NED KELLY IS SUPPOSED TO HAVE BUILT NEAR GLENROWAN IN 1875

( Image from Ned : The Exhibition )

Here is another Guest Contribution from Dr Stuart Dawson, this time challenging the notion that in 1875, when he was 20 years old Ned Kelly won a contract and built a ‘granite house for a settler near Glenrowan’. I am hoping somebody who knows a thing or two about building houses out of quarried granite can comment on the technical aspects of such an undertaking and if he or she thinks smashing rocks in prison for three years would equip anyone with sufficient skill to build such a lovely dwelling. I would also like to know how long it would take, and how many men would be needed, because I suspect it would be a very long time and require a substantial commitment which I seriously doubt Ned Kelly the larrikin Greta mob delinquent would have the ticker for. This very much looks like another Jones flight of fancy to me….

As I mentioned in a previous comment, in a June 1962 Walkabout article Ian Jones claimed that Ned Kelly learned to work granite in Beechworth gaol, and had also done building work in a convict gang. In 1875, Jones says, Kelly contracted to build a granite house for a settler near Glenrowan, which still stands today. One is almost star struck by the lad’s talents… But is it true? Did he really contract to build a granite stone house? Or is it just Jones’ early enthusiasm for Kelly the wunderkind?

First question: why would a settler contract with an ex-convict with no stone building track record and who failed grammar and arithmetic in third grade, managed to pass arithmetic (but not grammar) in March the next year (Jones, Short Life 2008: 24-25), then left school. Hardly the background education from which a fully planned stone house would be successfully designed, contracted and built? Why would the settler have signed a building contract with such a semi-literate character as Kelly? I suggested that perhaps there is some flight of fancy dating back to 1962 worth further enquiry, and here is the result.

First, it is good to see no claims of Ned building stone or granite houses in Peter Fitzsimons ‘Ned Kelly’. Indeed, the period from February 1874 to later in 1875 passes there without so much as a hint of stone masonry, not even a stone wall or gate post. And the story is much the better for it.

By contrast, Grantlee Keiza’s ‘Mrs Kelly’ has Ned so busy from 2 February 1874, when he got out of gaol, to mid-February 1875 when according to Kieza he started work as an overseer at the Burke’s Hole sawmill when Saunders and Rule took it over after Dixon went bankrupt, that it would take three or four Neds to keep up the pace. Between those dates, covering barely a year, Kieza on pages 170-172 has Ned

- cutting trees as a faller,

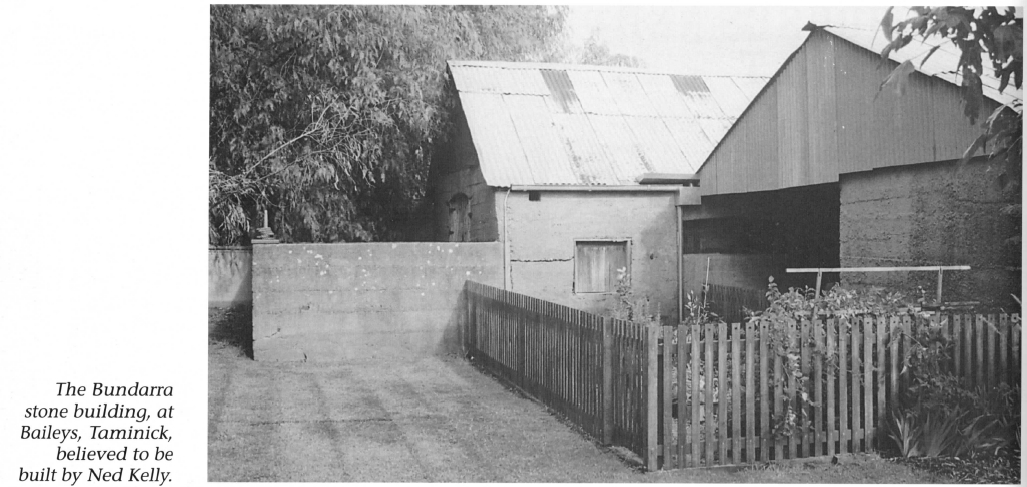

- fencing at Bailey’s Taminick vineyard,

- helping construct the Bailey family’s wine cellars,

- helping construct a pink granite house (Farnley) at Chesney Vale, also

- contracting to build a different granite house near Winton with rock quarried from the Warby Ranges and carted by bullock team,

- ploughing on the 60,000 acre Evans run near Moyhu,

- working as a travelling shearer on the Murray,

- breaking in horses near Greta, and

- riding in the Lake Rowan steeplechase. !!

What can we make of this given that Kieza gives no source references for the two different Kelly-built granite houses he lists? Confusion, I think, in a book that is generally excellent for listing the extensive Kelly clan criminology. No other book claims Kelly built two granite houses! McMenomy helps set the record straight on this matter:

In his Authentic Illustrated History (2001), 55, McMenomy wrote that “a stone house at Chesneyvale, near Winton, was recorded as one ‘built by the Kelly brothers … in 1875’. … The house was built of pink granite quarried in the Warby Ranges, 25 kilometres away”. It seems that Kieza found two references in different places to the same stone house and interpreted them as two different houses. As he gave no source references for the stone house claims that will remain a mystery, but rest assured there was only ever one actual granite house that was claimed to be Kelly-built. To continue in McMenomy, “The construction alone was a major feat: some of the blocks measured three feet square and six feet long, and the whole building sat on a made up bank overlooking Lake Winton”. The Geelong Gaol people told me it took one man one day to make one of the bluestone blocks in its walls. How long would such a house take to build with huge granite slabs quarried and carted 25 kms by bullock dray? Wouldn’t we have heard about it in the O&M if the Kellys were responsible during the months of building? And who says the Kelly brothers built it? Jim was in gaol and weedy Dan was 14 (born 1861), hardly a strapping labourer. McMenomy’s references for the building venture are Jones 1962, who tells us nothing about the claim; Jones’ ‘Short Life’, which we will review shortly, and Dean and Balcarek’s ‘Ned and the Others’, 1995, pp. 89-91.

In Dean and Balcarek’s 2014 edition, pp. 139-140 we find that Henry Freitag, for whom Ned and his friends helped construct the house, was in fact an “excellent builder”, which suggests that Ned at best did labouring if he was there at all, possibly driving a bullock wagon, not building. Mr Freitag was also one of many who claimed to have looked after Dan Kelly after he escaped from the burned Glenrowan Inn, so it is no surprise to find him linking Ned to his house building. Balcarek and Dean write p. 130 that “Ned next worked for a German selector and builder, Henry Freitag, who needed his skill as a trained stone mason. They helped build the ‘Bundarra’ wine cellars for the Baileys at Taminick, and later worked at many other buildings around the district. Today there is only one stone house that is known to be still standing, at Cheney Vale, north-west of the Winton Swamp, which was built of a beautiful pink granite by the Kelly brothers. It was called Farnley and belonged to the Bakewell family. The date 1875 is cut in a stone on the back wall under the verandah. Mr Feitag said that he would employ Ned Kelly anytime, but flatly refused to re-employ young Dan as he was too lazy”. In other words, nothing at all links Ned and Dan Kelly to the granite house, or to any other of the many houses and barns he was claimed to have helped build, but a fairy tale. The Taminick wine cellar tale is also later oral history.

Jones’ ‘Short Life’ (2008 edition) is the final place where there might be some hope of a reference for Chesney Vale that is better than Dean and Balcarek’s old timer’s tales. On p. 100 we hear that Ned did fencing at Bailey’s Taminick winery. Not building a stone cellar, mind, just fencing. As an aside, Jones tells us that it may be here that Ned “developed a taste for claret with his favourite meal of roast lamb and green peas”. Why did Jones decide that this was Ned’s favourite meal? Because that’s what his last meal was in the condemned cell before execution. That’s what was on offer in the Melbourne Gaol. Not even a potato or carrot, just a basic plate. No bread? Jonesy, really? But back to Chesney Vale: on a man-made embankment on the shore of Winton Swamp, “Ned contracted to build a granite house. Probably helped by Brickey Williamson and 14-year-old Dan, he quarried pink granite in the Warby Ranges behind Glenrowan and hauled it to the site with his bullock team. … When it was finished – probably in the first months of the new year – Ned carved ‘1876’ in one of the granite blocks at the back; and early landmark in his third year of hard and honest work”.

References, Mr Jones? Pp. 436-7, “builds granite house by Lake Winton, Louise Earp, ‘The Kelly Story’ condensed from Mr Ashmead’s book, and from stories told by J. McMonigle Snr, who died mid-1930s, and his daughter”. Let’s check Ashmead’s uncondensed manuscript book’s later typescript, ‘The thorns and the briars’, a 1922 Christian morality tale about the Kellys. There is nothing to the point about ‘Winton’, ‘Chesney’, ‘swamp’, ‘lake’ ‘house’, ‘stone’, ‘granite’, or the truncated ‘buil’ for build or built, in it. Nothing connects McMonigle to the Chesney Vale/Winton house. We are left with Jones getting a fanciful hand-me-down story from the McMonigles in which Ned had a bullock team and just happened to win a contract to build a granite house that required quarrying huge pink granite slabs up to 6’ by 3’ by 3’, and carting them 25 kms from the ranges to Winton north with his bullock team, with the help of a few friends and relatives including 14 year of Dan and their neighbour, the stock thief and layabout Brickey Williamson, then doing excellent stonemasonry to the point of completing the house and carving the year on it, with no mention at all of Mr Freitag. This is such obvious nonsense it should never have been printed.

Clearly what has happened is that Jones has heard various stories of Kelly building houses all over the north east, believed the one about Chesney Vale, and concluded that as the house was granite, and as Ned (with little Dan) was said to have helped build it, he must have had stone masonry skills. The only place Ned could have learned stone masonry was in gaol. Both Beechworth and Pentridge had bluestone quarries, and the Williamstown defence works and Graving Dock used stone blocks. Ned was at all these gaols, therefore he must have learned stone masonry in gaol otherwise he wouldn’t have been able to build the granite house at Chesney Vale. See? The logic is impeccable…

Before we accept any of these stories at all, let’s first consider the basic question of whether Kelly ever learned stonemasonry in gaol, on which all the house building stories depend. On 2 August 1871, aged about 16, Kelly was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment for feloniously receiving a horse, and sent to Beechworth Gaol. ‘Feloniously’ receiving means receiving with a proven intent to on-sell the stolen property. That is why he got double the sentence Wild Wright got for ‘illegally using’ the horse.

On 19 February 1873 he was moved from Beechworth to Pentridge under new regulations by which all prisoners sentenced to terms of two years and upwards were removed to Pentridge “to undergo penal discipline”. Under the system in force, “A male prisoner on entering Pentridge is received into the A division. He is confined in a separate cell for a period of as many months (not exceeding twelve) as there are years in his sentence. He is allowed one hour’s exercise daily in the open air, but receives a smaller ration than that given to prisoners engaged at active occupations. He is employed in plaiting straw for hats, or such other light work as can be carried on by a single person in a cell” (Penal and Prison Discipline Progress Report 1870(2ndSession), vi). In other words, going by the progress report, Ned would have been in separate confinement engaged in unskilled light work, the gaol equivalent of basket-weaving, from 19 February to mid-June 1873, not learning stonemasonry.

Ian Jones accepted that Kelly started in A Division but held that as he had only a year and a half of his sentence still to serve, he would only have spent six weeks in A division before moving to B division (Short Life 2008: 90-91). Against this,

(a) Jones noted that while no prison record has been located for him at Beechworth, “his troublesome behaviour [there] is indicated by a loss of three months remission from his total sentence”, suggesting both that that any deviation from standard procedure by Pentridge is unlikely, and that if he was a disciplinary problem he was probably sent to solitary, possibly including dark cell confinement given his Jerilderie letter complaint about “Beechworth and Pentridge’s dungeons”, thus disrupting his alleged stonemasonry education;

(b) the purpose of the 1873 transfers was “to undergo penal discipline” for those with original sentences exceeding two years and Kelly was unquestionably in need of it. He had quite a reputation by then, from his first time inside: back in 1870 he had been mentioned in a prison report as “the bushranger Kelly and his mate” [Power] (Penal and Prison Discipline Progress Report 1870 (2ndSession), Minutes of Evidence, Q. 160); and

(c) Beechworth and other places were gaols; Pentridge, the hulk Sacramento, and Williamstown, were not gaols but penal establishments (Penal Establishments and Gaols. Report of the Inspector General for the year ending 31 December 1873 (Melbourne, 1874), table, p. 11).

Being transferred from a gaol to a penal establishment to undergo penal discipline suggests no concessions such as reducing the standard time spent in A Division solitary for new prisoners by a claim of having served a chunk of time in another gaol already. This needs further research, but there is no reason to accept without good evidence Jones’ unreferenced assumption about only 6 weeks being spent in A Division in Pentridge when the progress report suggests otherwise.

The progress report continues: “At the end of his term of separate confinement the prisoner is transferred to the B division. In this division the prisoners occupy separate cells, but they work and take their meals in company”.

It is entirely speculation by Jones that upon moving to B Division Kelly did any stone-cutting. He wrote p. 91, “Ned probably worked in the quarry gang, cutting bluestone from the prison quarry in its huge quarry, and in the stoneyard, where he passed the day chipping and facing bluestone blocks. He may have worked in the gangs continuing to build A Division with slow, rigorous craftsmanship”. Against this, the second progress report held that “as a means of making the industry of the prisoners available to cover the cost of their own maintenance, it will be necessary:-That every prisoner shall be compelled to adopt such a handicraft as he may appear to be best fitted for”. As an unskilled labourer Kelly would have been put to work labouring, not taught stonecutting or masonry which were classed in gaol as skilled trades. He might have lumped bluestone, but he sure wasn’t cutting or shaping it. Whatever work he did there was short-lived, as on 26 June 1873 he was sent to the prison hulk Sacramento, apparently because of a need for labour at Williamstown.

Jones claimed that Kelly’s transfer to the hulk Sacramento “represented recognition of his ability as a stonemason and the chance to live and work under conditions at least as good as those in C Division”. This is completely wrong. None of the men from the Sacramento or the Williamstown Battery sentenced to hard labour were used as stonecutters, masons, or bricklayers in 1873 or 1874, which are categories of convict work in the tables of prison labour (Penal Establishments – A Return to 31 Dec 1873, 11; Penal Establishments – A Return to 31 Dec 1874, 13). Other than a couple of blacksmiths and a bootmaker the Hard Labour men on the Sacramento and at Williamstown over those two years were all unskilled labourers. Kelly, never the brightest, added another seven days to his sentence when on 21 August 1873 he handed two rations of tobacco to another prisoner. On 25 September 1873 Kelly was sent to the Williamstown Battery. On Tuesday 13 January 1874 he was reported in the Williamstown Governor’s diary for “disobedience on the works this day”. The works were breaking stones into small pieces (breaking spalls), not learning stonemasonry. He was freed by remission on 2 February 1874 after spending at least the previous seven and a bit months doing unskilled labour on public works throughout his time on the Sacramento and at Williamstown. There was not a jot of recognition of any stone working skills Kelly might possibly have possessed. He did hard manual labour and basic stone breaking. The house building stonemasonry tale is looking even more ridiculous now than it previously did.

For the convenience of anyone wanting to check the evidence of prison labour not performed by Kelly in 1873 when he was in Pentrige, then the Sacramento, then the Williamstown Battery, the summary of work performed by prisoners that year is in Table 6 at the back of the attached report. There was no stonecutting done by any prisoners at either of those establishments in 1873, not in the subsequent report for 1874 (which obviously covered the time to February 1874 when he was released). I added yellow highlighter on some bits for convenience.

Another interesting thing: in his Jerilderie letter page 14, Kelly famously claimed that “I never worked for less than two pound ten a week since I left Pentridge”. Isn’t it curious that his prison record shows that upon his release, he was paid £2-10-11, saved from his prison labour? McMenomy ‘Authentic Illustrated History’ (2002: 55) noted that “This was a considerable wage at the time. Skilled farm ploughmen earned five shillings for a fifteen-hour day, or £1-10s for a six-day week”. One might observe that farm labourers, fencers, shearers, bullockys and probably tree fallers – all of which Kelly is supposed to have done during his “straight years” – paid less. Why would anyone pay Kelly £2-10s a week for any of these jobs when they could employ anyone else for half the cost? Kelly is lying (again); boasting to impress.

We can also see in McMenomy p. 87 the photo of a guy in a suit that was held to be Ned Kelly for many years by Jones and others before being debunked. It’s the one Jones called “Gentleman Ned”. McMenomy writes under it “This very rare image [shows] Ned in his best tweeds, trying to lead an honest life as a sawmiller”. The fiction dates back to Jones in the Walkabout article from June 1962, where on p. 16 Jones wrote, “A photograph taken about this time [of being overseeres at Burke’s Hole sawmill] shows a sober, bearded young man dressed in a suit, with waistcoat and tie”. Of course, over five decades of mythmaking later, it was proved not to have been a photo of Kelly. The tale of his ever being a sawmill overseer is also likely horseshit from the Jerilderie letter. Further to that, he said in the Jerilderie letter that his time as an overseer was “1875 or 1876”. That kinda rules out building a granite house in Winton… Not that he probably even came close to doing either. Being a rambling gambler and stock thief was more his thing.

Attachment Penal-Establishments-A-Return-to-31-Dec-1873-done-4-May-1874-No-26.pdf

Another howler from Jones in Short Life 2008: 93, talking about the £2-10-11 that Kelly left prison with in February 1874 – he says that “With the 2 pounds 10 shillings and elevenpence he had earned as a stonemason he headed home by train”. As the Penal Returns for 1873 and 1874 that we have been examining in this post show, no convict stone masonry was done by the Sorrento convicts or the Williamstown Battery convicts in either year.

What is happening here is another frequent storytelling device of Jones at play: he repeats and repeats a claim so that it comes to seem true and unquestionable. But it is wrong, totally wrong. Kelly never got any earnings from stone masonry as there was no stone masonry whatsoever done by those convicts at those particular places. What he earned to take away when he left gaol was from labouring; just another one of the 25 labourers sweating it out at Williamstown in 1873 (see page 11 of the 1873 Penal Return attached to the post immediately above.) The most convicts accomodated at Williamstown in 1874 was 30 (see page 13 of the Penal Return attached here.)

If you have a look at Jones’ notes for convict life at Pentridge, in Short Life 2008 page 435, they are all drawn from journalist’s descriptions from November 1875 and later; one is 1877. They are not about Kelly, who had left Pentridge over a year previous to the first article. It is another exercise in creative writing, and very well written at that – but it is fiction, not historical Kelly facts.

Attachment Penal-Establishments-A-Return-to-31-Dec-1874-done-27-May-1875-No-38.pdf

That was Sacramento convicts, not Sorrento convicts – damn autocorrect…

Attachment

There’s not much left in “The Short Life” book by the time you take all this made up stuff out. Perhaps it should be called “Ned Kelly – The Short Book”.

Darren Sutton is a respected Beechworth historian. I remember he once posted a link to a newspaper article (I think it was an article about industry in the NE) that had a reference to Ned having for a short time been a gold miner at Stanley at around 1875. That seems quite possible to me, although I guess it can never be conclusively proven.

Don’t forget that in between all that stone cutting he did at Williamstown, Ned was also a valued centre half-back for the Seagulls. https://www.williamstownfc.com.au/teia-miles-williamstown/10-latest-news/2127-ned-kelly-was-a-tough-centre-half-back

It is very doubtful to the pojnt of impossibility that Kelly ever worked on the sea walls off Gellibrand or the artillery bunkers at Williamstown as that Seagull article claims. Appendix A (No. 2) to the Penal and Prison Discipline Progress Report 1870-2nd Session No18 sets out how prisoners from the Sacramento were employed on shore work. Those working on shore were separated into to two classes. Because of the progression times indicated there, Kelly would have been in the second, lower, unpaid class during his time on the Sacramento and not out and about on shore, which was for the first class convicts. In any case they did not let the hard labour convicts out to play football. When Kelly was moved to the Williamstoewn Battery and went up to the first class, he did labour on the Alfred Graving Dock. If the good Seagull would like to produce any evidence to the contrary, many would like to see it.

I had the link to the gold mining article that Darren discovered somewhere but can’t find it. Anything is possible pending investigation.

Hi Anonymous, here is the link to that Royal Commission progress report, 1870 second session, https://pov.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_GB/parl_paper/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fSD_ILS$002f0$002fSD_ILS:36735/one

And you might enjoy this newspaper counter-article to Captain Seagull’s claims, ‘A WILLIAMSTOWN historian has poured cold water on a claim notorious bushranger Ned Kelly played for Williamstown Football Club’, https://www.heraldsun.com.au/leader/news/historian-disputes-claims-notorious-bushranger-ned-kelly-played-football-for-williamstown/news-story/e15c38bc946617a83588030a19bbb56e

Hi again Anonymous, it took me a while to find but here is the textand source for that gold mine reference than Darren posted. The source is an article by the Mines Inspector and posted in the Ovens and Murray advertiser.on page 8 of the O&M, 8 August 1896.

“PRINCE OF WALES.

This property was first developed in ’72, and has a reef of from 2 to 5 feet. It was first worked by a man named Whitton, better known as “Ballarat Harry.” He sank a shaft about 100 feet, and proceeded successfully for several years, and then abandoned it on account of the water. It then fell into the hands of one Ned Kelly, who labored on a new shoot which realised 25 dwts. to the ton. Latterly McKibbin. Clingin and Stone took it up under miners’ rights, and this party recently celebrated a satisfactory crushing. With a view to raising a capital sufficient to efficiently work that property, it was placed a few months ago into the hands of Messrs. Coles and Co., of Melbourne who are understood to be floating it on the market. It is owned by the proprietors of the Birthday, and has a reef of from 2 to 5 feet”.

Re Prince of Wales mine see https://bih.federation.edu.au/index.php/Prince_of_Wales_Mine

“Located on Cobblers Lead in Sebastopol the Prince of Wales Mine was formed in 1862. On 23 June 1863 shares were quoted on the Melbourne Stock Exchange at 1,750 pounds each. The Prince of Wales Mines closed in 1875. It obtained 209,071 ozs of gold.” The website gives a list of over 100 shareholders circa 1866.

Back when this little mining article was first noted here, in 2017, I thoiught anything is possible re some Kelly involvement. But now it is pretty clear that some 1892 mention of a mine misdated 10 years after its actual foundation, with Ned Kelly thrown in, into a shareholder held mining company, elimnates the suggestion of Ned Kelly’s ownership. The writer is just passing on some old gossip from a long abandoned mine that ceased to exist in 1875. How would poverty-stuck Ned have aquired ownership of a gold company? This has to go in the folk-myth pile, the same pile that has him building haouses and barns all over the north east and every man jack loo-llo brain claiming they were descendants of sympathisers or witnesses to the gang’s activities, one of the most popular being the dozens if not hundreds of people said to have been involved in making the armour. Remember that Ian Jones has dozens of men, women and children cheerfully involved in the armour-making. Grab your ‘Short Life’ and fall about laughing.

There is another curiosity in Jones’ Kelly story. Back in the 1962 Walkabout article he had convinced himself that in Pentridge prison “Kelly found one of the ferw people who had ever tried to understand and help him. It was the gaol’s Roman Catholic priest, Father O’Hea, a priest who had known Ned Kelly’s father and had been friend and counsellor to the Kelly family during their years at Wallan and Beveridge. … There can be no doubt that Father O’Hea was basically responsible for the transformation which took place in Ned during those years in prison. The ned Kelly who emerged from Pentridge was teh Ned Kelly who has been almost forgotten: Kelly the honest man, Kelly the timber worker, Kelly the boxer, Kelly the overseer, Kelly the shearer”.

The story of Father O’Hea’s remarkable influence on Kelly was maintained to the end: in Short Life 2008: 91 we are told that “O’Hea must be seen as the greatest single influence on Ned in his convict years. The Chaplain’s philosophy of life, conveyed with the presence and humour of a born storyteller, provided the perfect antidote for the bitterness left by Ned’s encounter with [Constable] Hall. Just as importantly, it would arm him for the coming encounter with [Constable] Flood and his crimes against the Kelly family”.

What are we to make of this story, maintained and publicised for some 60 years? Kelly entered Pentridge on 19 February 1873 and was transferred out of Pentridge to the hulk Sacramento on 26 June the same year. Are we supposed to believe that Father O’Hea worked this almost miraculous life transformation in four months, assuming Kelly ever saw him on an individual basis which “required a warder to protect each of the ministers whenever they were in the cells” (Second progress report on Pentridge 1870, Q. 177). Jones’ claim that “the Chaplain’s philosophy of life … would arm him for the coming encounter with Flood” beggars belief. That would be the Flood that Kelly later repeatedly vowed he would roast alive in a log if ever he laid hands on him.

I suspect that this is another instance of cart-before-the horse storytelling. Since his early years Kelly led a life of predatory crime including highway robbery and ended up in gaol twice. After the second stint, he allegedly had three “straight years” according to Jones, although they are looking much less straight now than they did to Jones in 1962. The logic seems to go like this: Because Kelly had “straight years” (if he did), something must have straightened him out. That must have been Father O’Hea while Kelly was in Pentridge, because – just like learning stone masonry – it couldn’t have happened anywhere else. Therefore Father O’Hea transformed Kelly and the proof is the “straight years”…. Somehow I’m finding this increasingly hard to believe..

If Ned Kelly ever built that house, then I built the Taj Mahal, and I did it all on my own.

Hi Sam, Eugenie Navarre has a photo of yet another stone house built by Kelly on page 78 of her ‘Knight in Aussie Armour’, see attached. She says on page 77, “His skills extended to stonemasonry. In the mid 1870s he was employed by stonemason Henry Freitag to help construct a stone building on Bundarra for the Bailey family, at Taminick close to Glenrowan and also worked on other buildings in the area.”

Of the Chesneyvale house shown in the photo at the top of this post, she wrote “The stately stone house Farnley at Chesneyvale … was either Ned working with Freitag or perhaps he did it himself with labouring help.” So there we have it – Kelly is not only a genius stonemason but perhaps a master builder as well;. It’s amazing what a couple of years’ gaol education can do for a man.

And it is great to read in places like Jones and Corfield that so many people were glad to give Kelly a second chance and turn his new-found honest talents loose on their various elaborate building projects, all of which he seems to have accomplished successfully between February 1874 when he got out of stir, and some time in 1867 (or at latest by early 1877 when he had enough of this new honest life and did something naughty with Whitty’s bull).

When he wasn’t running a timber mill, or shearing, tree felling, fencing, bullock-driving, gold mining, etc. Not to mention getting in “thick as thieves” as it were with the Baumgarten horse stealing ring….

For a sensible review of Whitty’s historical reality, and of Jones’ fanciful mythmaking about it, see http://www.denheldid.com/twohuts/the-case-for-james-whitty.htm

Attachment

You really don’t like Ian Jones do you Davey? Perhaps a little bit more respect is warranted?

No and No.