Its an often-overlooked fact that for at least two thirds of the 140 years since his death Ned Kelly was widely regarded as a violent criminal and not much more. The claim that he was something more was only developed in the last 50 years or so by a variety of ‘pro-Ned’ authors, a narrative that was largely devised and then nurtured tirelessly by Ian Jones who used to be regarded as Australia’s foremost expert on the Kelly story. But now, that has all changed.

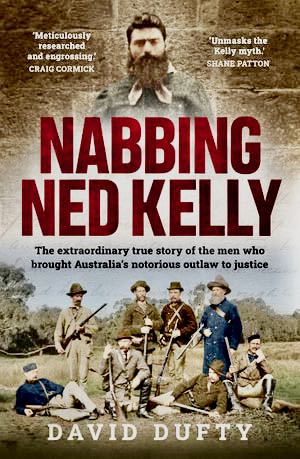

Beginning with Ian MacFarlane’s 2012 ground-breaking publication ‘The Kelly Gang Unmasked’ there has been a steady roll-back of the story Jones made popular because of a comprehensive re-examination of the historical basis for it. The Kelly legend has been gradually unpicked and is being reconstructed in a stream of scholarly works that have followed. ‘Nabbing Ned’ is the latest.

What’s different about this work is that instead of starting with the modern-day version of the Kelly story and critiquing it, Dufty ignored it and went back with a fresh pair of eyes to the historical archives and reconstructed the story from what was recorded there. His interest was not so much Ned Kelly but the police that hunted him down. What he has produced is a fascinating and scholarly work that’s easy and enthralling to read, extensively footnoted and referenced, and full of original insights and surprises, not just about the activities of various policemen and the way the hunt was managed, but also of the Kelly gang. Dufty looks at and has something interesting to say about almost everything in the story.

Comparing what he found in the archives with what the modern-day story had become, Dufty then identified a host of faults and fallacies, he solved a few longstanding puzzles ( the ‘shooting’ of Ned Kelly by Hall, the ‘rockets’ at the Glenrowan siege….) – and he identified a handful of controversies that will be debated for quite some time, such as who the writer of the Jerilderie letter was, and who was the creator of the suits of armour. He also left stuff out: Dufty ignores or mentions only in passing myths that make up part of the outgoing narrative that aren’t supported by anything in the historical record. For example, except perhaps for a signature on a marriage licence there is no independent record of George King ever existing, let alone, as Ned Kelly claimed, being a principal in Kellys stock thieving syndicate, so Dufty doesn’t talk about King. Regarding the many myths surrounding Fitzpatrick he writes “There are varying accounts of (Fitzpatrick’s) seduction of Kate but they’re all wrong. Not only is there no evidence for it, Ned Kelly himself denied that it happened”. He also writes “It is also said that Fitzpatrick was an alcoholic and that he died of cirrhosis of the liver but he wasn’t and he didn’t”. Chucking out rather than laboriously debunking red-herrings and unsupportable myths leaves the narrative cleaner and clearer. Dufty also refuses to be impressed by Kellys overblown self-aggrandising accounts of brawls and drunken escapades: the entire Lonigan ‘squirrel grip’ incident gets three sentences!

Duftys description of the way in which the perpetrators of what Jones called the “Whitty larceny” were tracked down and arrested is masterful. This incident was the theft by Ned Kellys stock thieving syndicate of eleven horses from the Myrhee Run, leased by James Whitty, in 1877. Dufty reveals how clever and dogged the detective work was in solving the crime, how police tracked down the true identity of the criminals who used false names and one by one made arrests and got closer and closer to the mastermind behind it all, ‘Mr Thompson’ who was finally revealed to be Ned Kelly. Warrants had been issued for his arrest when the ‘Fitzpatrick’ incident blew up.

Duftys research enabled him to directly challenge the core myths of the story, such as the one that says that the Courts were down on Kelly: “It is said that the courts had it in for him, yet the opposite was true. Browsing court reports in old newspapers I discovered that district magistrates either through corruption or fear went easy on crime, using any paltry excuse to acquit. Prosecutors struggled to produce witnesses who failed to appear or changed their testimony on the stand, or simply vanished before they had a chance to testify”

In fact, Dufty points out how convenient it turned out to be for the Kellys that several characters involved in the saga disappeared without explanation: we already know of George Kings unexplained disappearance but what about Moris Solomon who was supposed to appear to testify against Dan Kelly, or Alexander Whitla, the Benalla pound keeper who would have been a key witness in the Baumgarten horse thefts case? Both these people disappeared from the area and were never seen or heard from again. And what of Bill Frost : “Since his breakup with Ellen, Frost had been a frequent victim of crime. He had been shot in the face ( he said the shooter was a station cook who had recently left town and was never located) and he had had multiple horses stolen” Dufty doesn’t say it but the reader is left to wonder about the awful possibility of their being skeletons in the Kelly closet, a secret tally which could have been increased by four if McIntyre hadn’t escaped Stringybark creek.

Another core element of the Legend, barely mentioned by Dufty because of its complete lack of support in any of the historical archives, is Ian Jones great claim about the Republic of North east Victoria. Dufty writes “There was no mention of a secret army in the days following Glenrowan. There was no sectarian conflict between Irish and English or between Catholics and Protestants in the district. The selectors were not an angry organised political movement: most succeeded financially and the wealthiest were indistinguishable from squatters. Ned Kelly did not have a political bone in his body but rather was motivated by greed and revenge”

Two really important and fascinating additions to the record that are discussed in detail in ‘Nabbing Ned’ are the roles played by James Wallace, a schoolteacher mentioned only three times in Ian Jones account of the outbreak, and detective Michael Ward, whom Dufty describes as the ‘real hero’ of the story. Standish, the police Chief Commissioner is also revealed to have been a positive hard working and clever participant in the saga, a very different reality from the one portrayed in the pro-Kelly literature where they prefer to focus on sordid rumours about his private life than what is actually known about what he did.

Wallace was a schoolteacher at two small schools in the district, while he was also the Postmaster at Bobinawarra. He wrote to Standish late in 1878 and offered to assist in the hunt saying that as school was out over the summer he had spare time and could act as a scout. In fact, Standish quickly discovered Wallace couldn’t be trusted, catching him out in a lie. However, in July the following year Nicolson met Wallace and was taken in by him, and offered to pay him for information. Wallace said his reward would be to do his civic duty and didn’t want to be paid. In fact, Wallace was a former schoolmate of Joe Byrne and was a double agent who greatly interfered with police operations. Delays in the arrival of police intel by mail were tracked to the Post Office he managed. He admitted to being able to write letters in other people’s handwriting, and to forging their signatures. He was used to writing long reports and was well educated – Dufty believes these skills were made use of by the gang who intimately involved Wallace in the writing of the Jerilderie and other letters. Eventually police concerns about his behaviour resulted in him being transferred out of the district but not before he had begun collecting scrap metal and mouldboard for his father, whom Wallace said was a blacksmith. In fact, Wallace’s father was a storekeeper!

John McQuilton described Detective Michael Ward as ‘a deceitful man with an odious local reputation’, Ian Jones castes him in a similar light and yet Dufty nominates Ward as the true hero of the story! The difference is that Duftys assessment was based on the record of what Ward achieved and not on the results of a campaign of intimidation, lies and vilification that began with the Kellys who threatened to put Ward in a hollow log and roast him alive if they ever caught him. He received death threats in the form of letters and drawings of coffins, and black crepe, his movements were tracked and monitored by sympathisers – even his pet dog was poisoned – a campaign that was encouraged by Wallace who may well have been an author of some of these letters and all of it motivated by the fact that the Gang rightly understood Ward was a danger to them. Ward knew the Kellys from long before the outbreak and was involved in the hunt for the gang from the start, the Wombat search parties were his idea and he was at Harry powers lookout above the King Valley when Kennedy got to Stringybark creek. Ward chased and nearly caught the Gang when they fled to the flooded Murray river immediately after the police murders, Ward went to Euroa immediately after the hold up there and interviewed George Stephens among others, he cultivated a network of informers and spies that enabled him to keep the pressure on the Gang, he fed misinformation about Banks and police activities to the Gang, he monitored Wallace and cultivated a relationship with Aaron Sherrit.

“Wards strategy was simple and brutal at its core. By monitoring their families and friends and by tracking their movements, to cut off the gangs supply lines. To pull the net slowly ever tighter.”

Kelly supporters will no doubt be expecting police misbehaviour to be excused or ignored but Dufty doesnt do this :

“He was a layabout and a drunk who was known to visit a local hotel for brandies before lunchtime. In briefings superiors could smell alcohol on his breath. He was on familiar terms with the Quinns and other miscreants but not enough to feel safe from them. He was a loafer not a crook and as such had the respect of neither the police nor the criminals”

What one realises when learning about Wards dogged pursuit of the Gang is that contrary to the perennial claims of the Kelly sympathiser community, the police hunt was not an ineffectual clown show that achieved nothing. In fact, despite the activities of sympathiser spies and double agents like Wallace and Sherritt, despite the various perpetually highlighted mistakes and blunders made by the police and despite even the vagaries of weather which on more than one occasion blunted the chase by obliterating tracks, the police campaign greatly circumscribed the behaviours of the gang, applied constant pressure to their supporters and inhibited their activities and movements so effectively that eventually under all that pressure the gang cracked. The result was to plan a mad violent confrontation to end it all at Glenrowan, a plan that fortunately was so ill-conceived it failed almost from the first moment. The Outbreak ended less than two years after it began.

This book is an absolute pleasure to read, perhaps more so if you are familiar with but unhappy with the versions of the story made popular by people like Ian Jones and Peter Fitzsimons. I noticed a few typos and trivial errors, and the Kelly sympathiser mob found enough to give them the excuses they wanted to dismiss it. What they’re doing sadly for them is failing to see the wood for the trees: the big stories of Ward and Wallace, among many others in this book are much more important than the correct sequence of Steeles middle names, or Mrs Reardon’s first.

Duftys fresh perspective and willingness to think aloud and outside the box has opened the entire story up for a new generation of readers, and for the existing generation of readers provides answers and explanations that are satisfying, as well as challenges that are new and intriguing.

A marvellous book.

Hi David, I agree with your comment about the book, that ” Chucking out rather than laboriously debunking red-herrings and unsupportable myths leaves the narrative cleaner and clearer.” It is indeed, as you say, a marvelous book.

Nevertheless I want to raise for discussion something about Dufty’s short treatment of the Fitzpatrick incident. I suggested in my ‘Redeeming Fitzpatrick’ article that Kelly had been drinking in the old shack prior to being alerted to a policeman’s presence by Mrs Kelly’s two young girls, upon which he rushed to the front door of the main house in a passion with a small bore pistol drawn, when Mrs Kelly had already moved forward with her fire shovel raised, intent on driving Fitzpatrick out of the house. Dufty writes, “Ned later accused him of drawing his revolver and shouting, ‘I’ll blow your brains out!’ Maybe he did.”

Yet little supports that possibility: Fitzpatrick had been fully confident that he could arrest Dan regardless of any possible resistance in the absence of Ned (see Whelan in RC Minutes), and his revolver was still holstered when Dan got it from him in the ensuing fracas. The idea that Fitzpatrick had drawn his revolver is entirely Kelly fiction.

Dufty suggests that when Ned arrived at the door he deliberately fired wide as a warning shot. But why, if Fitzpatrick had not drawn his revolver, would Kelly fire a warning shot into the room rather than into the air when he was standing immediately outside the open front door at the time? Why wouldn’t he have, as he boasted he could have, just rushed in and used his fists? And if Fitzpatrick had his revolver drawn, why would Kelly not have shot him dead given his later words that he had first thought the uniformed policemen might have been Constable Flood, who had had an affair with Kelly’s since dead sister Annie while her husband Alex Gunn was in jail, unsurprisingly for horse theft, and who he stated on many occasions that he would like to roast alive in a log?

I am unpersuaded by the warning shot theory although not dismissing it outright. It seems premised on the possibility of Fitzpatrick having drawn his revolver before Ned rushed to the front door, which is not correct. I still propose that Kelly was irrational from drinking when he rushed to the door, which helps explain his mirror response when afterwards speaking of the incident, accusing Fitzpatrick of having been drinking prior to the event, a classic narcissistic trait. It also helps explain Kelly’s later comment that he could not have missed at that short distance if he had wanted to shoot Fitzpatrick. Not if he was sober, anyway.

Fitzpatrick received the next bullet in his wrist as he threw up his arms in self-protection when Mrs Kelly attacked him with a fire shovel, as per a telegram from Benalla to Wangaratta police station alerting them of the incident. Here too there was no need for a warning shot if Kelly had already fired once. The wound from which the bullet was extracted attests to the small bore of Kelly’s weapon. Kelly’s pistol discharged a third time when Fitzpatrick twisted it away from himself, as he asked Kelly if he intended to murder him. It was only then that Kelly seems to have realised who the policeman standing in front of him was.

Kelly said to Fitzpatrick afterwards that he would not have fired had he known it was him. It is clear from what Kelly said then and later that he would have had no regrets if the constable had been Flood and was shot dead. In any case Kate Kelly later told the police that it was only her distress that had stopped Kelly and another man (who proved to be Byrne) from killing Fitzpatrick directly after the incident. This had nothing to do with any attachment between her and Fitzpatrick that some have sought to see; but her horror at the prospect of watching a blatant murder. After that incident, Ned and Dan Kelly (and Joe Byrne) went bush, living in a hut a mile or so from Stringybark Creek.

This is not to reject wholesale what Dufty has written (or perhaps, dismissed) about the Fitzpatrick incident. It is to rather take up the challenge as to whether Fitzpatrick might have drawn his revolver and threatened to blow Mrs Kelly’s brains out, ion response to Dufty;s comment that “Maybe he did”. As above, I just can’t see it, and not for want of looking.

Hi Stuart

what youre trying to work out is why Ned Kelly fired at Fitzpatrick and missed, not once but at least twice. Dufty thought it might have been because Fitzpatrick had drawn his revolver – and you think not becasue it was in the holster when Dan got hold if it – but couldn’t he have put it back before it was then removed by Dan?

The comment of Ned Kellys that he wouldnt have fired if he had known it was Fitzpatrick seems more like a post-fact attempt to ingratiate himself with Fitzpatrick, as part of the attempt to get him not to report it. Same with the offer of a few hundred pounds. Same with Kate Kellys claim to the police she was the one who stopped Fitzpatrick from being murdered. All the Kellys were lying about this debacle and nothing any of them said can be trusted.

But if Kelly was saying he thought Fitzpatrick was someone else, Flood perhaps, that makes it harder to understand because he didnt shoot to kill Flood either!

I dont think we will ever be able to pin the exact detail down, but I think we know the rough outline ; Kelly fired a gun, Fitzpatrick was wounded.

But your explanation for the wild and inaccurate shooting – if one accepts they weren’t any kind of warning shot – that Kelly might have been drunk is reasonable enough but unprovable.

I did like your suggestion about a ‘mirror’ response. Ive not heard of that before but Ive noted to myself many times how the kelly mob were constantly accusing police and others of the things they themselveselves did in much greater measure – sexual impropriety being the obvious one, drunkenness and alcoholism being another, horse stealing another and of course going out to kill people!

It was a good book and I am due for a re-read. The theory about the rockets, or rather lack thereof was interesting. Wallace was obviously a malignant tumour for both the gang and the police. It was good to read the information on Ward and Standish. Now, how about a review of Kiezas book?

Love from Dinks.

I am preparing my review of Kiezas The Kelly Hunters right now and will have it up for your Easter reading!

May I ask if it has ever been proven that the photo of Joe Byrne that appears in Nabbing Ned Kelly, and others, is in fact of Joe Byrne the outlaw? Doesn’t bear any resemblance to the known image of him strung up after death at Benalla to my old eyes, even allowing for the injuries. Appreciate any advice.

Thanks, OJ.

According to the Iron Outlaw site, that photo was identified as Joe Byrne by Ian Jones who made it available to the public for the first time in his book about Joe Byrne and Aaron Sherritt, The Fatal Friendship.

There is a really interesting commentary on this topic, also to be found on Iron Outlaw, written by ‘ Captain Jack Hoyle’ which concludes by saying it would be prudent to label this photo as ’thought to be Joe Byrne’’ until conclusively proven.

https://www.ironoutlaw.com/captain-jack/will-the-real-joe-byrne-please-step-forward/

I dont have access to my copy of the Fatal Friendship right now but others might and can check to see if Jones mentions how he came to the view it was Byrne. Ian Jones famously misidentified a similar photo as Ned Kelly and made quite extravagant claims about how certain he was that it was Ned, only to eventually retract them when it was clear to everyone else it wasnt Ned Kelly. So, now that youve asked the question I am looking forward to hearing from anyone else who has thought about that photo : did Jones get this one right, or is it another one of Jones many assertions which were accepted uncritically by his supporters but which will turn out to be wrong?

Hello David,

Many thanks for your reply. I certainly agree, Captain Jack Hoyle’s study on Joe Byrne is a very interesting read.

As the photo has appeared in a number of books on Kelly I was keen to learn if the id had been ‘conclusively proven,’ to quote Captain Jack, at some stage that I had missed. Appears not!

Thank you for the opportunity to raise the question.

Regards, OJ.

Just noting from a few hours of research, Alexander Whitla may “not have been seen again” in the area after 1877ish – but that may have been because he moved to the Newcastle area of NSW, and died in 1917; his second wife died there in 1923.

And another thing, Moris Solomon was actually Moses Solomon according to the papers of the day. He was known only as Unger according to one of the witnesses. To say he was never heard of again may just be because he possibly changed names after serving 18 months hard labour for fraudulently concealing the insolvency property of Davis Goodman, the storeowner where the “Greta atrocity” occurred in 1877 (which Solomon felt was his right since Goodman owed him a lot of money). I also noticed that Judge Bindon was busy with the other fellows’ horse-stealing (including the Baumgartens and Studders) so there seemed some overlap of events and people.