This post is the final Part 8 of a review of Bill Denheld’s Ned Kelly – Australian Iron Icon: A Certain Truth (2024), by Stuart Dawson. It asks, why was Kelly’s murder trial moved to Melbourne? And what has that got to do with a republic? As before, bracketed numbers, e.g., (xx), refers to pages in Bill’s book.

The full text of this entire 8 part review can be downloaded as a single finished article at the end of this post.

Why was Kelly’s murder trial moved to Melbourne?

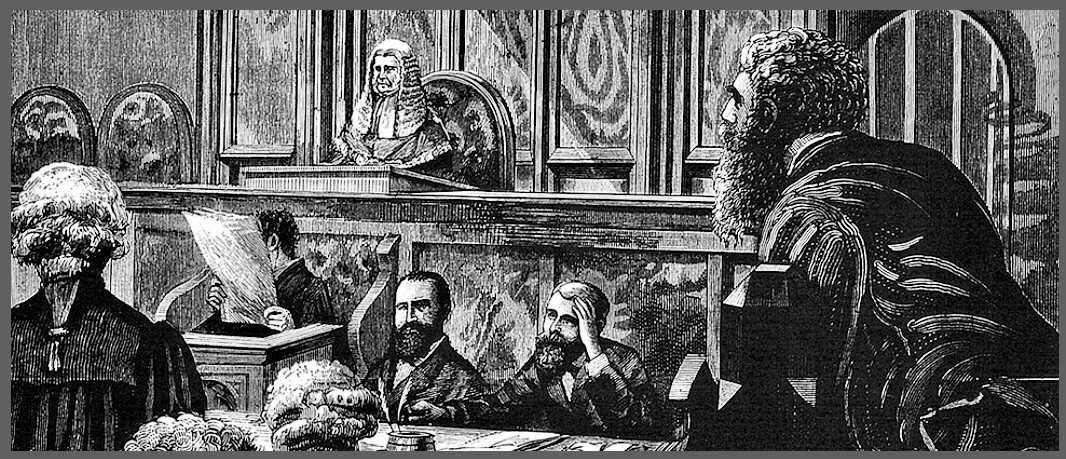

Bill suggested that a climate of unrest in the north-east was the motivation for Kelly’s trial being moved from Beechworth to Melbourne: “It had become apparent to [Kelly’s solicitor] Gaunson and [his barrister] Bindon that if the case had been held in Beechworth, Ned would have got huge sympathiser support which may have caused more social unrest in north-east Victoria for the authorities and ‘make it possible that Kelly would be acquitted’” (294). Concerned by these various possibilities, the Crown moved the trial venue to Melbourne avoid them. This idea builds on Bill’s previous argument for a huge number of Kelly sympathisers in the north-east which I rejected above, bypasses discussion of the reason the trial location was moved, and ignores that Gaunson failed to lodge an affidavit against the relocation. The facts are as follows:

Crown Prosecutor Smyth’s application to relocate the trial to Melbourne centred on two key points in his affadavit: “That from the lawless conduct and threatening demeanour of some of the relations friends, and sympathisers of the said Edward Kelly. I believe efforts would be made to intimidate certain of the jurors on the jury panel of the said Assize Court, and that some of the said jurors might probably be thereby deterred and intimidated from finding a verdict in accordance with the evidence”, and “That should a jury find a verdict of guilty against the said Edward Kelly, I verily believe that those members of the said jury who live in the country districts of the said bailiwick would be liable to serious injuries in their persons, families, and property at the hands of the said relations, friends and other sympathisers of the said Edward Kelly” (Argus, 20 September 1880, 7).

Gaunson asked for and was granted an adjournment to consult with his client, Kelly, who was given the opportunity “to show cause why the venue should not be changed from the Beechworth Assize Court to the Central Criminal Court at Melbourne”(Herald, 16 September 1880, 3). When Gaunson next appeared to discuss the matter he “proceeded to contend that it was unlikely that the local jury would consist of sympathisers with the prisoner”. Smyth said, “‘No, we do not think that for a moment, but they may be in terror of the sympathisers.’” Gaunson then ignored the standard legal process and did not lodge any affidavit of objection on behalf of his client Kelly. As a result, Judge Barry followed the standard legal process, stating, “’It appears to me that my duty in this case is very simple, for there is no counter affidavit here. I am clearly of opinion that enough has been disclosed to justify me not only in granting the change of venue, but also in demanding that the change should be made.’ The application was accordingly granted.” (Bendigo Advertiser, 23 September 1880, 2).

Graham Fricke’s suggestion in his Ned’s Nemesis, cited by Bill, – that “the Crown applied to Barry and asked for a change of venue because they suspected there was enough sympathy in the north east to make it possible that Kelly would be acquitted and Barry went along with that, and this was probably unfair” (306) – wrongly saw Smyth’s affidavit and Barry’s actions as some kind of conspiracy to ‘get Ned’. Coming from a Barry-bashing lawyer, this is alarming to see in what is supposed to be a proper legal analysis of a long established legal process of the day, that was followed to the letter. It is also directly contradicted by Smyth’s words quoted above from the Advertiser, that the Crown did not think that a Beechworth jury would consist of sympathisers with the prisoner. It is nonsense.

There is nothing in any of the exchanges between Gaunson, the prosecution, or Barry, about the north-east being in uproar in support of Kelly; or of a class struggle; or a land war. In Smyth’s affidavit referenced above he stated, “I am informed and believe that in the said bailiwick, and more especially in the neighbourhood of Beechworth aforesaid, the said Edward Kelly has numerous relations, friends, and sympathisers, amongst whom strong feelings exist in favour of the said Edward Kelly”, which says nothing about numbers, only intent. Gaunson had for whatever reason failed to visit Kelly in gaol for which Barry had granted him time, and so did not obtain the counter-affidavit that Gaunson himself had said was necessary. If anyone failed Kelly in this matter, it was solely Gaunson. But more likely Gaunson realised that he had no good argument to pursue.

Still more fatal to the suggestion of any potential significant sympathiser unrest are Gaunson’s own arguments against the relocation of Kelly’s trial from Beechworth to Melbourne. He drew attention to the fact that three of the outlaws were dead, that the police had prosecuted a number of people for acting as sympathisers, but that all of them had been discharged; that Parliament had not revived the Felons Apprehension Statute, and that notwithstanding, not one act of violence or lawlessness had been committed on their part since it ceased to operate (combining text from the Herald, 18 September 1880, 2, and Age, 20 September 1880, 3). As to the Crown’s claim that if the prisoner was found guilty at Beechworth the jury would be liable to serious injury in their persons and property, Gaunson argued that “the prisoner had a clear right to be tried where he was known for a number of years, and where the jurors would be able to give proper weight to any statements which he might make. There was no just reason for depriving him of the right to be tried by his fellow-countrymen. It would be a farce for the prisoner to challenge jurors called to try him in Melbourne. He did not know them and could not tell who had expressed an opinion against him or not, and that the affidavit of the Crown Solicitor did not justify a departure from the ordinary rule in these cases”. This is clearly a selective argument against one point only of the Crown’s affidavit, and Judge Barry reasonably asked if Gaunson had paid attention to its sixth point about armed gangs. Gaunson rejoined, “that in the pursuit of the gang a large sum of money was expended; but the inhabitants rather relished the performance, and were sorry when it ceased” (Herald, 22 September 1880, 2). That is, Gaunson is saying the overwhelming majority of north-east residents enjoyed and supported the Kelly hunt, and that armed gangs were not an issue, which is exactly the point about sympathiser numbers here.

Outside of that, it is clear from the evidence advanced in the Crown’s affidavit that it was reasonable to suppose that a Beechworth jury “may be in terror of the sympathisers” and that moving the trial to Melbourne was both lawful and in the best interests of securing an impartial trial. Finally, it should be emphasised that nowhere in any of the discussion about the location of the trial is there the slightest thought or mention of any form of north-eastern district political unrest. None. The idea that the trial was moved to Melbourne for political reasons is another Ian Jones-based fiction.

For context, Jones initiated the claim of a political Kelly in a 1967 Wangaratta TAFE Kelly Seminar published in Ned Kelly: Man & Myth (1968), and retained it in his Ned Kelly: A Short Life [2008], 368, claiming that there was “immeasurable” rural unemployment at that time: “land war hitbacks – stock killing, the burning of haystacks and farms – had been described in the north-east as ‘agrarian outrages’, the term applied to Irish rebel activity”, thus trying to link rural revenge with Irish politics. Jones’ suggestion of a general insolvency was firmly rejected by Weston Bate, Professor of Australian Studies, in his response to Jones in the Wangaratta Seminar. On p. 186 of Man & Myth Bates states that “in many ways this is the best time for selectors in Victoria. The majority of them were on their feet, and were able to withstand many of the problems that would have hit them hard some years earlier.” Jones clung to his tale of impoverished rebellious selectors regardless: “In this climate of threat and change the spectre of the Kelly trial hung like a thundercloud. It was too dangerous to stage it in Beechworth. … In this [Barry’s] view, Smyth’s argument – that a conviction would be difficult in Beechworth – not only justified the change but demanded it.” Jones thus deliberately misquoted – and in doing so badly slandered – both Smyth and Barry to support his fanciful claim that Barry moved the trial to Melbourne so as to ensure Kelly’s conviction. It is clearly a nonsense claim.

Fragments (or figments) of republican imagination:

Scattered throughout Bill’s book are fragmentary suggestions that some kind of coherent republican sentiment existed in north-eastern Victoria. Max Brown’s prefatory wild claim in Australian Son that “a declaration for a republic was found in Kelly’s pocket upon capture” gets an early mention (7), as does Age theatre critic Leonard Radic’s 1969 claim to have seen a printed copy of a declaration while in London in 1962 (21), a claim later withdrawn. Bill then changes the claim to Radic seeing “a block type printed leaflet spelling out a separation plan” (21), but Radic never said anything about a separation plan in anything quoted from him, and certainly not a spelled out plan. It was always an eight year old hazy recollection of a block type, printed declaration for a republic that Radic thought he had seen. Most alarmingly, Bill has a diagram that states that the Jerilderie letter “proposes a republic for North-Eastern Victoria” (21) when neither it nor the Cameron letter say any such thing.

To my assertion that the news fragment about letters found in Kelly’s pocket has no mention of any republican document or sentiment, Bill replies, “Who knows what came out of Ned Kelly’s pocket after his capture, and if it was a political declaration for separation, it is no wonder it was hidden from public view” (246); but this did not prevent him from speculating that “We can assume … that Ned Kelly had nothing more than a Victorian Land League handbill in his pocket based on the previous Rev. Lang’s [Victorian independence] declaration, or, it was nothing but a ‘quaint mock-up’ of such a bill, and that other copies of such bills were destroyed from public scrutiny by their supporters for fear of being charged with treason!” (244). As discussed in this review in the section, ‘Were there any significant colonial republican sentiments in North-East Victoria?’, the only indication of what Kelly had in his pocket is the word ‘letters’. There was nothing treasonous in Lang’s declaration and endless pamphleteering that spanned a couple of decades;[1] nor in anything published by the Victorian Land League. There is no historical basis for speculating about any potential government suppression of the Victorian Land League.

Bill says that “the government would silence any reference made to a republic” (254), and that “It can be surmised that in the 1880s nobody was publicly prepared to claim any support for a ‘republic’ movement for fear of being charged with treason which, if charged, carried the death penalty” (241). This is based on Chief Justice John Harber Phillips’ 2003 Kerferd Oration’s agreement with Ian Jones that that no one then would speak of a republic as it would be tantamount to treason. We find this suggested earlier when Bill says that “At the time [1880s] the republic idea was to be seen as treason, interpreted as ‘the crime of betraying one’s country, especially by attempting to kill or overthrow the sovereign or government’” (232). In the first place this confuses a treasonous act of murder or revolution (such as the French Revolution) with an aspirational goal of a monarchless state. In the second place it is totally wrong, as (unsurprisingly by now) were Jones and Phillips.

We find Mr Buchanan, a Protectionist, addressing a working men’s gathering in Sydney in 1880 and openly declaring “that he was a Republican by political creed”.[2] While many newspaper articles of the day discussed the French, American and other republics in less than glowing terms, a 780 word article in the Sydney Freeman’s Journal of 23 November 1878, 17 under the banner ‘Republic for Australia’ enthused, “It would indeed be a patriotic work to publish Dr. Lang’s ‘Freedom and Independence for Australia’ in cheap form; then the people would see what true loyally is, and we might soon hope to rise from the sleepy hollow to the greatness of nationality. Dr. Lang tells us ‘it is matter of sacred history that the only form of human Government that was ever divinely established upon earth was the Republican in the wilderness of Sinai’, and his reasons that we should be independent in 1852 are still more potent in 1878!”.[3]

An 1880 article headed ‘Mr Redpath’s Red Republicanism’ lambasted Redpath for a speech at a Land League meeting in Ireland in which “’he declared that kings and lords are the human vermin of society, who lurk and feed in the festering sores.’ He proclaimed it ‘a high crime and misdemeanour for queens and wives of lordlings to be sumptuously dressed by the robbery of the poor’, and that ‘he is of opinion that Ireland will never achieve independence except by the sword’”.[4] Of course it is true that the article is hostile to that republican speech; the point is that all three articles show that republicanism could be discussed openly in the Kelly period. A book by Audrey Oldfield, The Great Republic of the Southern Seas: Republicans in Nineteenth-Century Australia, traces a range of republican advocates right through the century. In 1880, the year Kelly was hanged, The Bulletinlaunched: “From the beginning The Bulletin was republican. It reported republican activity in Britain and forecast the end of the monarchy and the aristocracy; both were ‘absurd in principle and pernicious in practice’, for wisdom and ability to govern could not be inherited”.[5] What is notably absent from that book is any mention of anyone from ‘Kelly country’ saying anything whatsoever about a north-east Victorian or Kelly-led republic.

In Alfred Deakin’s memoir The Federal Story, he says of one of the key Australian 1890 Constitutional Convention leaders, Inglis Clark, that “his sympathies were republican, centering upon Algernon Sydney among Englishman, upon Mazzini in Italy and especially upon the United States, a country to which in spirit he belonged, whose Constitution he reverenced and whose great men he idolized”.[6]

Does this support Bill’s theory that proto-republican sentiments infused the Federation movement? No, it does not. The Rev. J.D. Lang’s vision for a fully independent Australia was articulated in a multitude of writings from 1826 to 1870 under his own and other pen-names. In an outstandingly detailed analysis of Lang’s views, Jan Lencznarowicz wrote that his influence “advanced the cause of an Australian federation which came into existence 22 years after his death”, but that in his time “the overwhelming majority of his countrymen opposed separation [from England] and abhorred republicanism”.[7] Lang was a Scottish Presbyterian minister; far removed from the Kellyland fantasy of Irish republican selector influences on Australian political moves towards the 1901 Federation, let alone anyone regarding the Kellys or their gang having any political views at all. Bill says, “Perhaps a republic of North-Eastern Victoria was never to be except as a notional hope with regards to hundreds of land reform meetings held during the early 1880s” (248). Again, Bill provides no evidence, and I haven’t been able to find any, that anything resembling republican sentiments was ever mentioned at land reform meetings when it is abundantly clear that such sentiments could have been mentioned regardless whether they were booed down. It was not treasonable to voice any such sentiments in Victoria, yet nothing anywhere suggests that many did. More to the point, nothing anywhere ever suggested a ‘Republic’ in north-eastern Victoria before the Bulletin mocked it in a spoof article in 1900, as my Republic Myth book showed. The idea of voicing an independent regional ‘Republic’ in the 1870s-1880s, independent of both Victoria and England, is preposterous.

Overall summary of comments on Bill Denheld’s Ned Kelly, Australian Iron-Icon: A Certain Truth

I had been looking forward to Bill’s book for over a year due to his decades-long engagement with the Stringybark Creek police campsite location issue and other interesting material on his Iron-Icon website,[8] in particular his evidence that the Beveridge Kelly house now being done up with taxpayer funding was never lived in by the Kellys, but was one of several speculation houses that Red built for rent or sale at that time while the Kellys themselves lived at Wallan throughout; and another article showing that the Whittys were not squatters as often held, but settler-selectors.[9] These are exciting and controversial topics, and well put together. Whether Bill’s SBC campsite and Sergeant Kennedy murder locations are ultimately right or not, he has presented a rigorously documented case that is clearly capable of analysis and testing. Yet his work and submissions have been ignored by the Heritage Victoria and DWELP/DECCA bureaucracy whose job it is to get the facts of heritage claims right. There is every reason for them to reopen this issue given they have poured a lot of taxpayer funding into a walking trail and signage that Bill argues lead to places where nothing happened.

There are three core topics upon which Bill and I disagree, that demanded this book review due to his devoting his chapter 12 to a critique of my ‘The Myth of a Republic of North Eastern Victoria’.

The first is Fitzpatrick, where the disagreement is about what happened in the Fitzpatrick incident. Bill has relied mostly on Kenneally’s 1929 Inner History for the framework of his presentation, and ignored my reconstruction of the incident in my ‘Redeeming Fitzpatrick’ article which proved that Fitzpatrick’s statements and testimony can be almost entirely independently corroborated. Bill also suggests two things unrelated to the Fitzpatrick incident: that he was involved in illicit horse dealing with Ned Kelly which led him to turn on Kelly to cover himself, and that he was a fall guy for a police establishment that was out to “get” the Kellys as potential social rebels as much as criminals. I have never seen the first proposition anywhere else and, as discussed in the Fitzpatrick section of this review, it is impossible. His next proposition draws on previous work, notably by Kenneally in 1929 with the theory of “loaded dice”, that the police were out to get the Kellys by hook or by crook – yet even in J.J. Kenneally there is not the vaguest suggestion of any political thought by the Kelly gang.

Secondly, the Kelly republic myth remains demolished as an elaborate fiction. Indeed, Bill accepts that; and despite his best endeavours to identify a proto-republican movement among Kelly sympathisers, it remains a myth. He discusses separation movements, the Victorian Land League, the Australian Natives Association, and the push for Federation, but provides little to suggest any involvement of Kelly sympathisers in any of these movements and none to show any involvement by the Kellys or their relatives. The closest it gets is that eight year old Ned went to the same school for half a year as did a boy who grew up to be a foundation member of the Berrigan (NSW) Federation League, and that Joe Byrne went to school with James Wallace who grew up to become a teacher and double agent, and who appears to have helped shelter the gang on the run after their outlawry, but whose involvement in the land reform movement appears unconnected with republicanism.

Even John McQuilton, whose The Kelly Outbreak imported the notion of a social bandit from British Marxist Eric Hobsbawm,[10]and attempted to apply it to north-east Victoria where it simply doesn’t work,[11] failed to unearth even one example of Ned having any political ambitions in his many addresses to captives during his two years on the run. The closest Kelly got was a rant at Glenrowan: Constable Bracken related that “When we were held prisoners in the hotel Ned Kelly began talking about politics. ‘There was one — in Parliament,’ he said, ‘whom he would like to kill, Mr. Graves.’ I asked why he had such a desire, and he replied, ‘ Because he suggested in Parliament that the water in the Kelly country should be poisoned, and that the grass should be burnt. I will have him before long.’ He knew nothing about Mr. Service but he held that Mr. Berry was no — good, as he gave the police a lot of money to secure the capture of the gang; too much by far”.[12] Kelly was a boofhead.

Third, Bill suggested (as have others, including Graham Fricke, Q.C.), that moving Kelly’s trial to Melbourne was an unscrupulous manoeuvre by the government with the connivance of Judge Barry to ensure Ned’s conviction. This is wrong and requires a response. Bill quotes Fricke from a 2008 ABC interview: “the Crown applied to Barry and asked for a change of venue because they suspected that there was enough sympathy in the North East to make it possible that Kelly would be acquitted, and Barry went along with that, and this was pretty unfair and … I doubt that he would have been acquitted in the North East, but his chances would have improved had he been tried at Beechworth” (306). This blatantly misrepresents why the prosecution asked for a change of venue. As discussed in the section in this review on why the trial was moved, the request was made to ensure a fair trial in which jurors would not be intimidated by threats of revenge. Crown Prosecutor Smyth explicitly said that it was not to gain favour towards a conviction: To repeat it here: to Gaunson’s argument “that it was unlikely that the local jury would consist of sympathisers with the prisoner”, Smyth said, “‘No, we do not think that for a moment, but they may be in terror of the sympathisers.’” Both Bill and Fricke have gone over the hills and far away here by ignoring what was clearly reported at the time.

Bill also suggested that as I have a doctorate, “the learned strive for acceptance from their peers and professional associates and professional people rely on financial income from studies, so money influences truth” (271). This implies that my view of the Kelly outbreak and the conclusions in my Republic Myth book were somehow influenced by a desire for academic acceptance or reward. As I said on David MacFarlane’s Ned Kelly: The True Story blog,[13] I have written none of my Kelly material as an employed academic and couldn’t give a rats about the university system. Further, I have not made one cent for any of my Kelly myth-busting research; all my articles are available free online. It is true that I had an honorary research position that gave me a free library card for a few years; but that’s it. The few Kelly academics are mostly Kelly enthusiasts: Molony, McQuilton, McMenomy; as are the lawyers who’ve written about Kelly: Waller, Phillips, Fricke, Burnside, Stoljar. The implication is wrong. I’m interested in myth-busting historical nonsense to make better sense of the past; that’s all. And because it’s fun. If you’ve read all of this review I hope that you too have enjoyed the ride.

To download the full text of this 8 part response to Bill’s book as a single finished review article click this link Ned Kelly 2024 and the myth of a republic of North-Eastern Victoria is still a myth

[1] Jan Lencznarowicz, ‘The Coming Event: John Dunmore Lang’s Vision for an Independent Australia’, Politeja, 16 (2019): 463-479.

[2] Evening News (Sydney), 29 March 1880, 2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/108746048#

[3] Freeman’s Journal, 23 November 1878, 17: “I will only refer to the great and Liberal statesman, Gladstone, who, I believe, values the utterances of the people of England. In the Nineteenth Century he says: “The day has gone by when England would dream of compelling these colonies by force to remain in political connection with her. On the other hand, she would never suffer them to be wrung from her. If the day should ever come when, in their own view, the welfare of those colonies would be best promoted by their administrative emancipation, the Liberal mind of England would say: ‘Let them depart; for if their highest welfare requires their severance we prefer their amicable impendence to their constrained submission’”, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/111097687

[4] Australian Town and Country Journal, 4 December 1880, 41.

[5] Audrey Oldfield, The Great Republic of the Southern Seas: Republicans in Nineteenth-Century Australia (Alexandria, NSW: Hale & Iremonger, 1999), 212-13.

[6] Alfred Deakin, The Federal Story: The Inner History of the Federal Cause (Melbourne, 1944), 30.

[7] Jan Lencznarowicz, ‘”The Coming Event!”: John Dunmore Lang’s Vision for an Independent Australia’, Politeja, December 2019, 477; 475.

[8] https://www.ironicon.com.au/

[9] Anon, “The case for James Whitty” (Unknown, 2001), 3, at https://www.denheldid.com/twohuts/the-case-for-james-whitty.htm

[10] https://www.youngfabians.org.uk/hobsbawm_britain_s_most_loved_marxist

[11] See the documented critique in my Republic Myth book.

[12] Argus, 30 June 1880, 6.

[13] https://nedkellyunmasked.com/

Two questions.

First: how do I get a copy of this book? Amazon says that it ships “within three to seven months.” I’d like it a little sooner than that.

Second: You’ve written eight articles talking about the things in this book that you disagreed with. Could you write one more article, in which you identify the things you either agreed with, or found interesting or refreshing? You mention a couple of such things in passing, but it would be nice to see more of that.

Hi David D., to buy Bill’s book, please go to Bill’s webiste at https://www.ironicon.com.au/ and order direct from Bill. It is AUD $50 Plus Shipping. Avoid Amazon, they were ripping him off with the handling charges.

The reason there were eight review posts was that I wrote the review over two weeks, but David wanted it in sections as he said no-one would read a 20,000 word blog post, so I agreed to split it into chunks. That’s why the order of blog posts differs from the finished full review article PDF. The reason I had to write a detailed response is because Bill devoted a whole chapter to critiquing my Republic Myth book.

If Bill had sent me his draft before publishing I could have alerted him to a range of errors such as claiming a £200 reward for the two Kelly brothers after the Fitzpatrick incident instead of one £100 reward for Ned only; then they would not have been published. But since it was published with a critical chapter dedicated to my Republic Myth book, and is out there in the market place, his critique couldn’t be let slide undefended.

I made it very clear both at the start and finish of my attached review article that it is critiquing only those parts of Bill’s book that clash with my book, and that there are plenty of other good things in it. That might not be clear when reading the varoius isolated blog posts, but I think it is quite clear in the full review piece.

I gather David is going to do a positive piece on Bill’s book for the blog, and I will be happy to contribute to that!

Attachment Ned-Kelly-2024-and-the-myth-of-a-republic-of-North-Eastern-Victoria-is-still-a-myth-1.pdf

That makes sense. If you write a nonfiction book, it is so important to find a subject-matter expert willing to fact-check it. Every book has errors. They creep in no matter how diligent you are. It’s a humbling experience, having your manuscript returned with copious notes and corrections. But you have to swallow your pride and go through that process.

I have helped fact check a few Kelly books and many times the author(s) won’t or don’t take on all the fix suggestions for whatever reason despite me showing supporting evidence. I fought really hard for some of it, too. No book is ever gonna be the definitive one in the Kelly world due to so much in contention in the saga. I wish I could have lent a hand to you with your draft, but you were in good hands from all I have heard. 🙂 Also, Stuart, a good piece of writing as usual.

Sharon, although I didn’t personally use you as a fact-checker, I have heard very good things about you in that regard, and if Stuart wasn’t available for Nabbing Ned Kelly I would quite likely have contacted you.

Here’s my unsolicited advice to authors, writing about this or any other topic. Near the end of the project (but not too near the end), find a subject-matter expert, and ask them to read a draft. Like Sharon, subject-matter experts might not be published authors, academics, or have other status-inferring credential. Like Sharon (or David, who runs this blog), they might just be bloggers. And they might not share your opinions, either. You might be worried that they will dislike the things you say. But by the time you’ve written a draft of a book, you know perfectly bloody well who the real experts are…. or you should. If you don’t, then something has gone very wrong.

This process is painful, because your fact-checker’s job is not to compliment you or praise you but only to tell you all the myriad ways you screwed up. That is always hard to take. But remember that they are doing you a favour. Despite all the criticism, they are only trying to help.

Sharon, given just how many took your advice or fixes and then gave no credit, I am amazed you bother to continue. As mentioned, every single publication has errors of fact. People who write books on many Historical subjects cannot be expected to know everything I guess. That’s why they should seek help. Not many are willing nor able 😇

Hi Dave and others, all the above is true. No one is an expert on everything and it is hard to get anyone to read draft work and give feedback. The feedback is not foolproof either! It is just an attempt to help out. I do not claim any expertise on things I haven’t looked at; and the number of Kelly topics I have looked at is small.

Contributing review feedback can be very time-consuming. It always means researching more about what is being reviewed, looking up sources in Trove and elsewhere to see if what is being said, claimed or quoted is correct, maybe reading another book or articles to get more understanding of what is being said…

For example, to review part of Bill’s book, which took most of two weeks work, I had to read Alfred Deakin’s history of Federation, search out material on JD Lang, search Trove for articles about the various selector movements, revisit my own past articles, and in the case of Bill’s book, assemble and summarise Bill’s scattered arguments from different parts of the book so they could be followed by myself as much as presented to others, then write about the various topics that I needed to. It’s a huge amount of work. Then nongs on the internet jump online and bag it without doing any work at all 🤪

For writing my own Kelly articles I have posted ideas on David’s blog here to see what comments turn up; sent short bits about particular issues to other people (often not academics) to see what they think, chatted to a few people, rewritten multiple times while doing further research, then for anything that has been through a university journal review process, added, subtracted, deleted, changed and modified various parts to address their reviewers’ comments often several times until the editor is happy that the reviewer’s feedback has been addressed. Then the editor adds their own changes which can be well meant but wrong, because they are looking for a clear presentation of something they are not an expert in; and they don’t see why some historical points and evidence need to be kept the way I wrote them because they don’t know the background context of the events and subsequent arguments of it’s not their specialty. That means more time putting up an argument to the editor as to why something should be left more or less as I wrote it.

I’m lucky and grateful that Sharon was happy to look at a lot of my stuff and give feedback on key points where I have blundered as we all do when we write things. As anyone who reads this blog knows, I post comments that are mistaken from time to time, or are just ideas, or are exploring something, not trying to give the ultimate answer. There’s a discussion going on now about Arthur’s Glenrowan rockets claim under the previous blog topic. Will we solve it? I think it’s pretty well solved but we’ll see.

This is an open discussion that anyone in the world can contribute to. That’s why the internet is so good.

A great read, thanks Stuart.

It seems my reputation precedes me! lol Just don’t believe everything you hear about me! 😉 One thing I love is how we all work together to find truth, or the nearest we can to it, in the Kelly saga. Kinda hard to do when the eyewitnesses don’t even agree with one another nor did the newspapers of the day, and there were so many jealousies and personal agendas involved throughout the whole saga (a situation which persists to this day). As we each light another’s candle we can see more clearly, but watch out for the ever-present bushels some want to put over lights! Shine on!

Hi Sharon, you might enjoy these snippets!

Attachment