Having admired Grantlee Kieza’s 2017 ‘Mrs Kelly’, I was keen to have a look at Rebecca Wilson’s 2021 ‘Kate Kelly: the true story of Ned Kelly’s little sister’, thinking it would likely model itself on Kieza’s well-researched approach to Kelly history, albeit from a different angle to focus on a child of the family. Although it has been out for a while, I had not noticed it until I saw it in a bookshop a few weeks ago then got it from my local library. The first surprise was that Kieza’s book is not in Wilson’s bibliography; then again, neither are a number of other expected references for the topics she ranges over. The next surprise given the title and cover testimonials was noticing numerous seriously alarming historical errors and long-overturned Kelly myths when initially skimming through, which a fuller read confirmed. For those who expect a historically accurate narrative I say with Dante, “abandon all hope ye who enter here”. I will set out my main bones of contention in this review.

Wilson prefaces her book with the statement that Kate Kelly “if remembered at all, is known mostly as the fourteen-year-old, attractive younger sister to Ned and Dan who was harassed by Constable Fitzpatrick at the Kelly homestead in April 1878 when he arrived without a warrant to supposedly arrest Dan”. Here are four historical errors in one sentence: Kate Kelly is very well remembered and is written up favourably in practically every Kelly book of the last hundred years; Kate was not harassed by Fitzpatrick; he went there intending to arrest Dan if he was present (no “supposedly” about it); and as a constable he did not need to carry a warrant to perform the arrest of a suspect. Wilson lists my ‘Redeeming Fitzpatrick’ article in her bibliography which addressed all of these points and many more that Wilson blunders through, as we will see.

She announces her approach as “one that will use the tools of creative writing combined with historical research to present the remarkable story of Kate’s life from her viewpoint”. John Molony did something similar in his “I am Ned Kelly”, but Molony is absent from her bibliography. Indeed, there are no endnote references in her text to any of the sources she claims to have obtained her information from. As a result, the historical basis for much of her book is entirely guesswork. When the text diverges, as it does in many places, from historical evidence and previous research, one must assume the creative writing has taken over and that historical accuracy has ceased to matter.

Given her claim that she had tried to tell Kate’s story “as accurately and completely as the records available permit” (p. 337) one repeatedly wonders how such a lack of analytical rigor as seen in her belief that Steve Hart and Dan Kelly were shot dead at Glenrowan “because, for me, that is the most predictable outcome for men who were engaged in a shootout with police”, survived the book’s editor. Dean Gibney saw the dead bodies in the Glenrowan Inn before fire consumed them, and testified that he believed from the way the bodies lay that they had committed suicide: “I did not see any [weapons in their hands], and I cannot say that I saw any sign of blood; in fact, my impression was that they must have laid the pistol upon their breasts and fired into their hearts; but that is only conjecture, for I did not see the wounds about them — about the bodies, or on the bodies” (RC, Q.12319, 12325). When asked, “Although you saw no firearms about them, you still think they committed suicide?”, he answered ,”From the position; I could not judge of anything except from the position in which they were lying. They lay so calm together, as if laid out by design (Q.12334). So: no sign of firearms on the two neatly lying bodies, and no sign of wounds or blood despite his theory that they must have “laid the pistol upon their breasts and fired into their hearts”. Yet we know a bag of poison was found on Byrne’s corpse. With no sign of wounds or blood on the bodies, poison is the logical, almost necessary, conclusion. Certainly not death from police bullets.

Wilson’s story of Kate commences with the finding of her partly decayed body in a lagoon following her suicide near Forbes, NSW, in 1898. What could be a short statement of the known facts takes eight pages of creative writing to describe, with lengthy digressions off the topic. For example: “Mustering sheep was exhausting work across such a vast countryside. Men in loose shirts, wide brimmed hats, worn trousers and old boots would scour the bush for the sheep. Their hips would rock from side to side in rhythm with the horse beneath them, and much cursing and cussing could be heard from the men above the disgruntled noises of the sheep as the crafty ewes scattered just when the riders didn’t want them to” (p. 11). Many pages in this book contain one or two paragraphs of description of scenery, buildings, or sundry people like the stockmen here, whether or not involved in the story of Kate. Some may enjoy this expansive approach to novelistic historical writing and they are welcome to it, but the story of Kate as presented in this book could probably be edited down to half its current length without much loss in my opinion.

A potted history of Kate’s childhood follows, missing much important detail and getting other things wrong. For example Wilson says, “The family moved from Avenel to Greta in 1867. They lived with Ellen’s sisters and their children, and they all helped each other start over again despite many setbacks, including a house fire lit by Red’s brother” (p. 17). This is written at the level of a children’s book (Gunning Fog Index 9.562, that is, someone who left school at 9.562 years old; grade 4 primary school. The previously quoted passage about the stockmen scores 10.53; grade 5). Contrast this with Ian Jones’ ‘Short Life’: “A rambling, delicensed pub provided a home for Kate and Jane Lloyd and their children, and now also for Ellen and her brood. … One chaotic summer night [Uncle James Kelly] turned up at the shanty, drunk and amorous. [He tried to seduce Ellen.] … he was eventually driven from the house with a stick after having a bottle of gin broken over his head. … the vengeful Jim set the old building alight. As the three sisters and their children ran to safety carrying what little they could, flames raced throughout their house burning it to the ground.” For this deliberate arson Jim was sentenced to death as the law required, later commuted as appears to have been standard practice for arson to 15 years hard labour. We learn nothing of this from Wilson.

Wilson says that before the Greta house burnt, “during her early childhood, Kate, her siblings, cousins and friends would tease each other with typical games and irritations on their daily walk through the bush-lined dusty streets of Greta to the Catholic School.” Contrast again with Ian Jones’ ‘Short Life’: “The local school was in the backyard of the shanty (‘between a fowl yard and a pigsty’), and the hard-working sisters undoubtedly shooed the younger children into it.” Wilson has invented a tale of daily school attendance somewhere in the town seemingly without having read Jones, although his first 1995 edition is listed in her bibliography. She might also have benefitted herself (and her audience) by reading and working with his revised 2008 edition together with Kieza’s ‘Mrs Kelly’ before writing about Kate. After the Greta fire Ellen took the younger children with her and worked in Wangaratta for half a year as a seamstress and laundress before putting a deposit on a selection with a dilapidated, dirt-floored, two roomed hut at Eleven Mile Creek, some four miles from Greta (Kieza, ‘Mrs Kelly’, 77-8). We hear nothing of the Wangaratta stint from Wilson.

Wilson says that soon after Ned Kelly’s release from a year in gaol for a violent assault, he was “falsely accused of horse stealing, when Wild Wright lent him a horse that Ned didn’t know was nicked” (p. 18). In fact, Kelly was charged both with horse stealing and with feloniously receiving; the stealing charge was dropped (as he was in gaol at the time the horse was stolen) but he got three years gaol with hard labour for feloniously receiving a horse knowing it to be stolen, i.e., receiving with intent to sell it on. This was proven in court and was a much more serious crime than using illegally. In fairness, many Kelly writers have failed to comprehend this difference and so wrongly bewail Kelly getting twice as much gaol time as Wild Wright; but they are different offences.

Page 20 is so full of surprises it has to be seen to be believed. According to Wilson, “Ellen’s ramshackle shanty [the 12 foot wide Eleven Mile Creek hut, a sly groggery] was at times a wild place filled with ugly men in filthy clothes whom her mother wrangled with perfection. Police were paid off when they visited as a necessary business transaction, and the rough venture kept the Kellys afloat. Kate became used to the presence of drifters, visitors and drunks. Over the years, Kate watched her mother take up with various lovers, including much younger men, who were often lodgers staying with them”. I wait with amusement to learn what the Kelly relative and sympathiser descendants made of this description of Ellen. And there is nothing in Wilson’s author’s note or the historical record to support the idea that Ellen paid policemen off. The opposite is true: Ellen was prosecuted for selling liquor without a license, amongst other things. Kelly relatives prosecuted each other at law at different times; Ian Jones discussed this in his ‘Short Life’, as did Doug Morrissey in his ‘Lawless Life’.

Things get really wild when Wilson asserts there that Alice King was the child of Kate Kelly and Constable Fitzpatrick, a view she had previously promoted in a Channel 10 television interview (https://youtu.be/irNEXQgXpH0). As Jones noted, Alice was three days old when taken to the lock-up with Ellen the night after the Fitzpatrick incident, i.e., 16 April 1878. Subtracting nine months places conception around 16 July 1877 (https://www.timeanddate.com/date/dateadd.html). Fitzpatrick was first posted to the northeast on 31 July 1877 (Record of Service) and would then have had to somehow meet up with her at least a few times if any kind of romance is envisaged. The timeline doesn’t work.

Wilson attempts to address this obvious problem on her webpage where she gives “some fascinating additional information to be included in the next reprint”, https://rebeccawilsonart.com/. She incorrectly claimed that Fitzpatrick’s occupation as a boundary rider before he joined the force “would have seen him travel widely across regional Victoria, including the town of Meredith where he abandoned a woman and the child they had together to join the force and skip town”. This employment was in Frankston, http://nedkellyforum.com/forums/topic/kelly-link-close-to-home-fitzpatricks-frankston-connection/. Clearly this is irrelevant to Wilson’s theory that Fitzpatrick could have impregnated Kate a month or two after joining the force. She mentions it to undermine Fitzpatrick’s character, but fails to mention that he paid maintenance to the woman, Jesse McKay, for the next two years, and that Meredith was less than 20 miles from Fitzpatrick’s family’s home at Mt Egerton (Molony, p. 96). This means Fitzpatrick could have known McKay and her family for some time in the past rather than her simply being road kill; and it seems unlikely to be a consequence of his work as a boundary rider given that that was in Frankston. To return to baby Alice:

Wilson’s hypothesis is that Alice King could have been a one-month premature baby, based on Dagmar Balcarek’s 1984 historical novel ‘Kate Kelly’ which is claimed to be “based on oral history from Kelly descendants and neighbours”, and discussion with maternity specialists. That still requires Fitzpatrick to have been busy shagging Kate from the day he arrived up north, despite the fact that police worked a 12-hour roster seven days a week and he lived in the Benalla police barracks some seven miles from the criminal-infested Kelly hut. Further, like all officers he had to account for each time he took a horse out of the stable and where he rode to, in the Diary of Duty and Occurrences maintained daily in every police station (see Haldane, ‘The People’s Force’ 1995, Ch. 3, fig.1).

Undaunted by such practicalities, she next theorises that “it is possible that Fitzpatrick was in the North–East district earlier than the dates reflected in his records”, i.e., that the police records are incomplete enough to permit her speculations of an affair dating before Fitzpatrick’s transfer north. She states that Fitzpatrick’s Record of Service provided to her by the Victoria Police Museum was marked ‘Official and Sensitive’; yet all records provided to anyone by the VPM are marked official and sensitive on the email as they come via the Victoria Police email system; and they are not for unauthorised reproduction or distribution for the same reason: as with any museum, permission must be obtained to reproduce the museum’s property. Fitzpatrick’s Record of Service itself is not marked official and sensitive anywhere; it is just a scan of the documents. Her implication that the police were trying to hide something is wrong. The entries in the record are sequential, and show the dates of transfers that begin with his transfer from Melbourne to the northeast on 31 July 1877.

During the three months after his joining the force, from 20 April to 31 July 1877, Fitzpatrick was based at the Richmond depot barracks. Wilson draws on a Royal Commission comment to show that at some unknown point and for an unknown period during that time he worked at Schnapper Point near Mornington (RC Q.183). She concludes from his Record of Service not showing a transfer to Schnapper Point that “This also means that Fitzpatrick could well have been in the Ovens district before the recorded dates of his transfer to Benalla in July 1877, which would have provided opportunity for Kate and Fitzpatrick to have met earlier.” That is, that Fitzpatrick might have somehow magically gone to the northeast while he was deployed at Richmond and (not a transfer) at Snapper Point in early 1877, working a 12 hour duty roster. Wilson’s speculation of an affair between Fitzpatrick and Kate Kelly during his first three months is utterly impossible.

Why was Fitzpatrick at Schnapper Point? We don’t know, but at a day’s ride from Richmond it was likely part of on the job training, in a district with which he was familiar having been a boundary rider there. He would have been housed in a police station during his time there just as he was at the Richmond depot, and later at Benalla, as was standard for unmarried constables (Haldane 1995, 106). During this time there was some unspecified incident about which Wilson speculates, “most likely Nicolson and Standish were referring to Fitzpatrick’s grooming of/sexual involvement with 14 year-old Anna Savage”. Wilson’s accusation of grooming is unfair given that Fitzpatrick married Anna in 1878. It is said this was a forced marriage, insisted on by Chief Commissioner Standish and Anna’s father. As a constable’s wage could not well support a family (Haldane 1995, 105), perhaps this insistence in Fitzpatrick’s favour may have been made despite Standish’s displeasure at the affair. Fitzpatrick and Anna had three children over a 12 year period, and he lived happily with her until his death (not from cirrhosis from drinking but from sarcoma, a cancer) in 1924; upon her later death she was buried next to him. It also illustrates the double standard of most Kelly authors who fail to condemn the “grooming of/sexual involvement” by 29 year old Alex Gunn who married Ned Kelly’s 15 year old sister Annie in 1869, and other liaisons between adult men and teenage girls in the extended Kelly clan. Further, if Fitzpatrick was wooing Anna Savage in Frankston (Molony, p. 96), he can’t have been gallivanting around the Ovens district trying to seduce Kate Kelly. The whole theory is ridiculous.

Wilson then turns to broad denigrations of Fitzpatrick’s character with selective comments by senior police that have nothing to do with Kate Kelly, and omits any mention of a number of character testimonials in his favour including two petitions for his reinstatement in the force after his dismissal by leading citizens in the Lancefield district, with one forwarded by parliamentarian Alfred Deakin. She should know these positive testimonials exist as she lists my ‘Redeeming Fitzpatrick’ article in her bibliography. But enough of her website musings about Fitzpatrick; let us return to ‘Kate Kelly’.

Chapter 4 introduces Hugh McDougall, a man who “was a little older than both Ned and Jim Kelly. He had been fond of Kate, as he was of all the Kellys throughout his youth”. The good-hearted McDougall “held no illusions as to the way the family was viewed, the illegal activities many of them had been party to and the consequences of that for Kate” (p. 24). According to Wilson, McDougall felt sorry for Kate and found her employment on a NSW cattle station under the name of Ada Hennessy (p. 29). However, the mysterious McDougall is not mentioned anywhere in Jones’ ‘Short Life’, Kieza’s ‘Mrs Kelly’, Corfield’s ‘Kelly Encyclopaedia’, or even FitzSimons’ ‘Ned Kelly’. He apparently existed, as Wilson’s bibliography lists a letter by him in the Forbes Family History Group Collection; but he appears to be an entirely fictionalised key character in her developing narrative. After the preceding issues, that sunk this book for me. It is not a “true story” of Kate at all.

But I will say a little more, as the book was one of the inspirations for a forthcoming short film, ‘A Walk with Kate’, which will be a gothic feminist interpretation of our heroine. Let us hope that the film is too short to feature McDougall (unless as a warlock). I did contribute a dollar so as to be able to post a comment in the Community section advising them to read my ‘Redeeming Fitzpatrick’ article if not too late for script adjustment. I’d like to see it when made as I have a soft spot for goth, but I don’t have high hopes for any historical sense given the film-maker’s claim that Kate’s “family’s response to the unwanted advances of Officer Fitzpatrick towards her allegedly helped launch the Gang’s outlaw status” (https://www.pozible.com/profile/a-walk-with-kate-film).

Wilson says that Kate as a first generation Australian spoke with an influence of her parents’ lilting Irish accent (p. 34); and indeed she tries to reflect that when writing Kate’s dialogue (“of course yer a bit edgy, for sure, for sure”). This is a common assertion by numerous Kelly authors including Ian Jones, but it is not correct. Colonial-born children had blended colonial Australian accents from around 1840 onwards regardless of their parents’ origins, and this also applied to the Kelly children (Philip Derriman, ‘Begorrah, Ned, or g’day’, Sydney Morning Herald, News Review, 22/3/2003; Bruce Moore, ‘Power of speech all ours’, Australian, Inquirer, 4/10/2008. p. 21).

On p. 39 a cattle station housemaid who had gone mad had decided to shoot one of the station family: “As he rounded the corner and lit the lantern, Jesse fired at him with a double-barrelled shotgun. … Blasted by both barrels, … his guts spilled out of his body as he landed on the floor. … His fellow card players jumped up at the loud boom from the gun. Dolph sprang from the lounge and ran through the dining room, thinking the worst as he ran. He heard another shot just as he got to the verandah. Jesse had shot herself in the thigh and still had the gun in her hand. She raised the long weapon and was poised to release another shot as Dolph landed on her and pushed her arm downwards, the spray of lead sending splintering shards from the floorboards flying but somehow missing her feet” (Gunning Fog Index 9.058). So: one double-barrel shotgun blast killing someone; seconds later a single barrel blast into her own thigh; then she blasts the other barrel into the floorboards. And then, “’Let me have another shot!’ Jesse screamed, and she struggled [after just shooting herself in the thigh] as Dolph pushed her to the floor and held her there”. What is this, Fifty Shades of Grey?

After twelve meandering chapters about Kate we get to the Kelly gang part of the story, which she launches with the Fitzpatrick incident of 15 April 1878. There is no background about stock theft, or the young Kelly boys stealing horses for reward, or the later Baumgarten horse-stealing ring that led to warrants for Ned and Dan Kelly amongst others. Unsurprisingly by now, McQuilton too is absent from her bibliography, so she would miss his emphasis on the police breaking up of the Baumgarten ring in which Ned Kelly was a central figure as a key factor in the lead up to Kelly outbreak. As Ned Kelly’s uncle Pat Quinn testified to the Royal Commission, “this affair of the Kellys commenced out of horse stealing first” (Q.17691). But we digress into facts; enough of that.

Chapter 13 starts with Fitzpatrick’s visit to the Kelly house: “Stonkingly drunk, still on duty from the races and trying to big-note himself once again, Constable Fitzpatrick put himself in the wrong place at the wrong time”. It’s rapidly downhill from there. The next page claims that Fitzpatrick’s visit was not to arrest Dan but “a ruse to see Kate … and she was holding the product [baby Alice] of their time together. … He had befriended Ned and then wooed his sister”. As discussed above, at this rate Fitzpatrick would have had to have been in the northeast from the minute he joined the force, three months earlier than he was sent there from Melbourne. After the ‘Fitzpatrick incident’ Wilson says, “From the Kelly homestead, the wayward constable made his drunken journey back to Benalla via yet another public house and then he located a doctor. He told the medic that it was a bullet wound in his wrist from the infamous Ned Kelly, but the doctor doubted the story and noted how strongly the officer smelled of brandy. Fitzpatrick declared that the Kelly family had tried to murder him. His confabulating grew the sensational story bigger and bigger, implicating ever more people, including Ned, family friend William Williamson, and Maggie’s husband William Skillion” (p. 97). Wilson’s entire treatment of the Fitzpatrick incident is impossibly bad, even as fiction. He was not drunk; he did not go to the Kelly hut after duty at the Cashel races (which were a couple of days prior) but from Benalla police station that same day; he did not make a drunken journey back to Benalla; etc.

Wilson’s careless, callous and factually wrong denigration of Fitzpatrick as arriving “stonkingly drunk” is the worst description I have yet encountered of the start of the Fitzpatrick incident, and yet another massive insult to Fitzpatrick’s descendants. Anyone wanting to know what happened can download my ‘Redeeming Fitzpatrick’ article which reconstructs, analyses and corroborates Fitzpatrick’s testimony (http://www.nedkelly.info/fitzpatrick.pdf). Why Wilson listed it in her bibliography apparently without reading it is a mystery. After the incident she continues: “Kate watched her mother argue with the policemen who arrived like a pack of wild dogs to devour her. They also took baby Alice, who was held with Ellen for three months at Beechworth Gaol”. Criminals’ misfortunes are always someone else’s fault, or the police’s fault; never their own… And why she described the arrival of the police to arrest Ellen as “like a pack of wild dogs” is another mystery; one that could have been addressed by some better historical research (see e.g., Keiza, ‘Mrs Kelly’, p. 223) and corrected before putting pen to paper.

Her treatment of the Stringybark Creek police murders is also wildly wrong. Her account seems to be built around Kelly’s Jerilderie letter. For one claiming to have done primary research, it is significant that Constable Thomas McIntyre’s lengthy and detailed ‘True narrative of the Kelly gang’, by the only surviving eye witness, is not in her bibliography. She claims that Kelly found “breech-loading Spencer rifles [and] fowling-piece shotguns”, plural, at the police camp, when it was a last-minute borrowed one of each. She has Lonigan “bombarded” by bullets” which she describes as a “lead shower” – it was one shot only. I will waste no more time critiquing multiple historical errors in this section. She omits any mention of Kelly and Byrne looting the bodies of the dead police; Kelly took Sgt. Kennedy’s watch, and Byrne wore the finger rings of Lonigan and Scanlon until the day he died at Glenrowan. Despite the fear and loathing the Stringybark Creek murders created in the public mind, Wilson claims “it was estimated that at least two thousand Kelly sympathisers existed among the small population in the north-east of Victoria (p. 116). This is also wrong; the largest contemporary estimate in any source was around 300, and that was likely too high.

Wilson describes Glenrowan as the climax of a Kelly gang “mission” to “create a new colony in the north-east of Victoria” (p. 149); specifically a “proposed Republic of North-Eastern Victoria” (p. 179). She derived this now dead and buried republic myth from Jones: “I have placed a lot of emphasis on Ned’s intention to create an uprising to form ‘The Republic of North-Eastern Victoria’. The late Ian Jones, well-known and respected Ned Kelly expert … appears to have been a strong believer in Ned as a political figure and that is how I see him too. There are many clues in newspaper articles, police testimony and oral history from Kelly or other family descendants that I believe make it a very feasible proposition” (p. 346-7). This theory, the central pillar of Jones’s Kelly biography, was entirely fiction and has been well and truly demolished, starting with Ian MacFarlane’s 2012 ‘The Kelly Gang Unmasked’. See my 2018 ‘Ned Kelly and the myth of a republic of North-Eastern Victoria’, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks19/1900551p.pdf. Leo Kennedy’s 2019 ‘Black Snake’ (also absent from her bibliography) contains a quote from a Kelly descendant who states that Kelly didn’t have a political bone in his body. It is unfortunate that Wilson was not up to speed and as a result has recycled disproven nonsense from Jones’ absurd Kelly republic fantasy.

Worse, she has actively distorted historical facts. She writes that “during the wait for the trial” (by which she actually meant the Beechworth committal hearing), Constable McIntyre “kept changing his account of what happened at Stringybark” (p. 186). It seems she has not read McIntyre’s ‘True narrative’, freely downloadable from the Victoria Police Museum website (VPM2990) and recent commentary on it (such as by Doug Morrissey), but has likely relied on Jones’ bungling accusations of perjury based on Supt. John Sadleir’s faulty memory some thirty years after the event (in his ‘Recollections of a Victorian Police Officer’) of what McIntyre had said to him back then. When McIntyre’s first statement was relocated after the Beechworth committal hearing and placed in the Crown prosecution file, it was obvious that McIntyre’s testimony was consistent over time; that Sadleir’s recollection of that first statement was flawed; and that Jones was wrong (on this and many other points). Wilson’s subsequent account of Kelly’s Melbourne trial is to me abysmally bad and baselessly insulting (and factually wrong) about Justice Barry’s conduct of it. My opinion is don’t even bother reading this part of the book unless you just want Barry-bashing fiction; instead, read one of the actual newspaper accounts of the trial (29 & 30 October 1880) on Trove.

On p. 250 Wilson portrays Fitzpatrick’s sister Jane as pushing her way through Kate and Jim Kelly’s hotel door in Sydney and demanding hush money for not her telling anyone that Alice is the daughter of Kate and Fitzpatrick. “Kate was eager to mess up the woman’s face with her fists” as Jane “ran for the stairs” while Jim restrained her, assuring her that Jane won’t be back. (Neither will this reader.) Sometime later Kate went to South Australia where, “shortly before Kate arrived in Adelaide, Mr Kreitmayer of waxworks fame had also taken a tour of figures and relics through the region” (p. 271). So far, so good (except for the misspelling of Kreitmeyer’s name). Then, “Kreitmayer’s extravagant purchase of Ned Kelly’s armour was the new drawcard displayed alongside the successful wax reproduction of the scene of the Kelly Gang at Stringybark Creek.” This is extraordinary nonsense in any book about the Kellys, even as fiction. Kelly’s armour was kept by the police after Glenrowan, not sold to Kreitmeyer.

One last matter: Wilson claims that the authorities allowed others to “mutilate” Kelly’s body after execution: “various parts of Kate’s beloved brother were divided out to men for examination and exhibition as trophies around the Melbourne medical and social scene. Whatever disturbed mess remained was interred in Ned’s supposed resting place” (p. 233). Against this unfortunately not infrequently made claim (based on a newspaper article of the day), the Governor of the Melbourne Gaol reported back to Supt. Nicolson that there was “no truth in attached newspaper stating that the body was given to Medical men after execution and no students at examination”. The matter was investigated at length by Fiona Leahy and Helen Harris (in Craig Cormick’s 2014 ‘Ned Kelly under the microscope’) who concluded, “Our historical research suggested that Kelly had not been dissected after his death and that the article in the Bendigo Independent, re-reported in several newspapers, was not true – that medical men and students had not ‘gone in heavily’ and made a ‘nice mess’ of Kelly’s body, nor souvenired parts of his head” (p. 26). It was sensationalism; what we would now call “for clicks”, and should be rejected outright.

I’m not going to spend any more time reviewing this book, but since it is there, something had to be said. To me it is insufferably bad as history in the parts discussed and for the reasons given in this review. Whether anyone likes its novelistic writing style is up to them. Large parts of it are entirely fiction, as are most if not all of the innumerable passages of dialogue given to its characters. Wilson’s prefatory statement that she “will use the tools of creative writing combined with historical research” should be taken as a red light: it is a work of fiction. Its text is unreferenced and it is serially at odds with well-documented historical facts. Yet it presents itself, title and all, as a true story. Indeed, the publisher states that “Rebecca Wilson is the first to uncover the full story of Kate Kelly’s tumultuous life”. I first spotted it in the Australian History section of Readings Carlton (then got a library copy). It is offered for sale in the Royal Historical Society Victoria’s bookshop, https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/product/kate-kelly-the-true-story-of-ned-kellys-little-sister-by-rebecca-wilson/. The centre section of historical photos and comments implies a factual basis for her tale. A couple of cover testimonials also imply that it will reflect actual history: Paul Terry, author of ‘The true story of Ned Kelly’s last stand’ said, “Rarely told in full, this is the fascinating life of one of the great characters in one of our greatest stories”. Rob Willis, National Library of Australia Oral History and Folklore Collections, wrote, “Thoroughly recommended not only to those who have an interest in bushranging and the Kelly dynasty but anyone who enjoys a well-written and riveting yarn, based on fact” – despite the NLA itself cataloguing the book as fiction, https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/6934961. (What “Kelly dynasty”, one might ask? Must be something in the Canberra water; mook juice perhaps.) I myself very much enjoy a well told tale based on fact, and will continue with Masuji Ibuse’s ‘Black Rain’ after I drop ‘Kate Kelly’ into the after-hours return slot at the library ASAP.

No wonder Doctor Doolittle loves you Stuart. Scorched earth policy seems de rigour for both of you. I didn’t think much of the book either but bloody hell, you destroyed Ms. Wilson. And her reputation. At least to the very small audience reading this little blog. Bravo.

Your problem Mark is that youre so used to putting up with the written garbage that permeates every nook and cranny of the Kelly world that youre shocked when someone has the audacity to call it out. This book is a shoddy bit of writing that purports to be telling the true story of Kate Kelly but as we all agree its riddled with errors and is full of holes. This author has appeared all round Australia on talk shows on TV and radio and in print promoting this nonsense and not one journalist that I am aware of ever bothered to check out her claims or challenge her about them.

Having said that I do like her Art, and if she just stuck to what she’s good at there wouldnt be a problem but her reputation as a history writer deserves to be in tatters.

Attachment

More than time, this author was exposed for what she has written. Total and complete garbage.

Good on Stuart for giving a fair dinkum review, that exposes Rebecca in a clear and concise manner.

She deserves to be exposed for the rubbish presented to the public as a true story, when it is total fiction.

Hi Mark, I have said nothing to impugn Wilson’s reputation at all, which is apparently mostly as an artist. This is a critique of a number of clear historical errors in her book. Plus, I will not stand for her abuse of Fitzpatrick. What I have done is critique historical errors that shower horrendous falsities on Fitzpatrick in particular, and provide corrections to various other historical facts. The book is presented by the publisher as a true story. It is not a true story. There are a stack of historical errors in it that are likely to seriously misinform about real historical events; you can see the historical endorsements straight up in the back cover testimonials.

You probably don’t know this, but Fitzpatrick has quite a number of descendants who are long sick of the mindless abuse heaped on their ancestor. As you saw with the Strahan book, Lachlan Strahan came to discover when he undertook his research that his own ancestor had been wrongly maligned by some within his own family based on falsities taken from Kelly nut “scholars”.

The same has happened with Fitzpatrick; a number of descendants over time have accepted the rubbish and lies and abuse piled on their ancestor by the Kelly crowd and simply written him off as a bad egg. My 2015 Redeeming Fitzpatrick article caused a significant rethink. Some of his descendants now realise that the Kelly stories and the attacks on him by Kelly enthusiasts were lies. No-one now has any excuse for piling arrant nonsense on his memory.

Thank you for taking the time to write this long review.

Thanks Dave. I could not find any indication in the book that it was a novel; it is presented as a true story or as truth based creative writing. As opposed to Balcarek and Dean’s ‘Ned and the Others’ which says up front in the first page that it is a novel. The author’s notes at the back confirm that the book is built on and intended to reflect historical research and argument. It is sold as a true history book, i.e., in shops and through the RHSV with no indication that it is anything other than fact-based history. No one forced the author to describe Fitzpatrick as “stonkingly drunk” when he went to the Kelly house in 15 April 1878. I and some Fitzpatrick descendants have had enough.

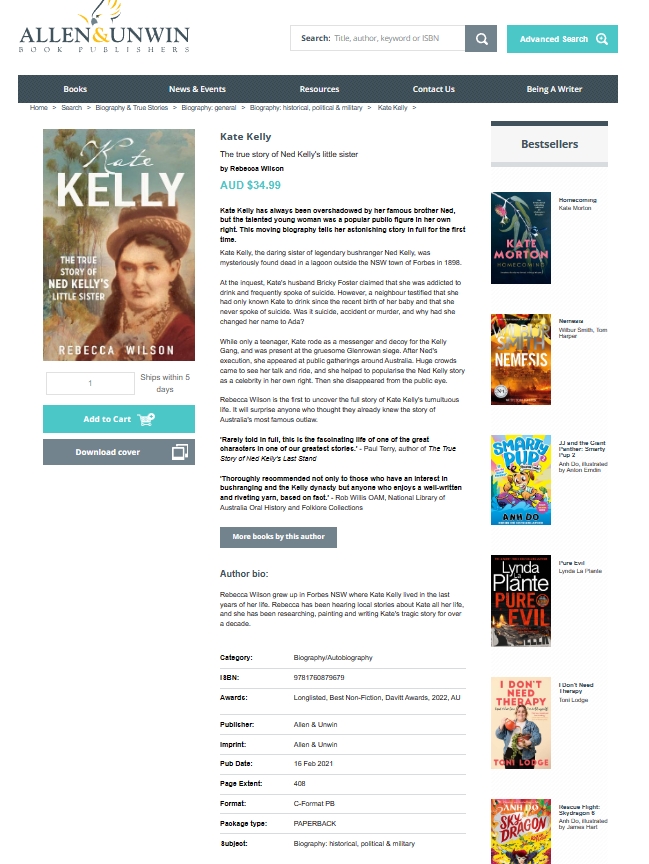

For anyone wondering, here is a screenshot of publisher Allen and Unwin’s catalogue listing for Kate Kelly. It is listed under Biography and True Stories; subcategory, Biography: historical, political and military.

The publisher states, “This moving biography tells her [Kate Kelly’s] astonishing story in full for the first time. … Rebecca Wilson is the first to uncover the full story of Kate Kelly’s tumultuous life. It will surprise anyone who thought they already knew the story of Australia’s most famous outlaw.”

There is no question the publisher represents this book as a factual biography that will uncover the full and hitherto unknown story of Kate Kelly’s life. Nothing there suggests it is a novel, or fiction, or that the prospective purchaser will be purchasing anything other that a factual narrative. As such, the publisher has classified it as biography.

In the book details at the bottom of the page, by way of further promotion, the publisher states under Awards, “Longlisted, Best Non-Fiction, Davitt Awards, 2022, AU.” Non-fiction…

Attachment

wow wonderfully written 😉