Ned Kellys plan for Glenrowan was described as ‘mad’ by a well-known Kelly sympathiser and spokeswoman for the Kelly story. As far as I know, no other Kelly sympathiser has ever challenged that description, and certainly no truly objective observer would disagree: even Ian Jones said it would have been a ‘criminal atrocity on a monstrous scale’. Let’s be honest about this: no sane person in their right mind would ever imagine for a moment that four men in home-made armour could defeat an entire police force. Claims have been made that the Kelly Gang were going to be supported by a small group of armed supporters, the so-called Sympathiser Army, but as far as I know, Ned Kelly didn’t ever mention such an army, and there is no evidence that such an army ever existed. What the actual evidence supports is that Kelly believed he and his brother and two friends were going to take hostages at Glenrowan and defeat the entire Victoria police more or less on their own.

My question is this: the plan Ned Kelly devised was clearly ‘mad’ – does that not mean he too was mad?

Quite apart from the very convincing evidence of Kellys madness demonstrated by his outrageous plan for Glenrowan, there is a lot of other evidence that supports the idea that by 1880 Kelly was ‘mad’ by which I mean out of touch with reality, not rational, unable to think straight, in some way psychiatrically deeply disturbed and unstable. This evidence takes the form of a series of letters he authored in prison, after sentencing and while awaiting the outcome of the appeals that were being made to try to spare him from the Gallows.

Look at the one he wrote on November 5th 1880. Kelly begins with this:

“The first thing I waited for was the last passenger train to pass at nine o’clock. I then bailed up a lot of men in tents around the stationmaster’s house as I suspected there were detectives amongst them. I then bailed up Mrs Jones’ Hotel, then Mr Stanistreet the stationmaster, and asked him if he could stop a special train with police and black trackers on. He said he could stop a passenger train, but would not guarantee to stop a special train with police and black trackers exactly where I wanted it”

“So then I bailed up the platelayers and overseer and ordered them to pull up the line a quarter of a mile past the station, so as the train could not go any further. My intention was to have the stationmaster to flash the danger light on the platform so as the stop the train, and he was to tell the police to leave their firearms and horses in the train and walk out with their hands over their heads, and their lives would be spared. Also to inform them that it was useless them fighting as me and my companions were in full armour and we could take the train and everyone in it; that the line was pulled up in front of them and I had a tin of powder behind them. So that if they attempted to return I would have blown the line up there as well”

The sequence of events is well known from many sources, but Kellys version is wrong : the very first thing he did was to attempt to lift the tracks in secret, but then, because he couldn’t he disturbed the men in the tents thinking they could help him – nothing to do with there being detectives among them but he was wrong again – they couldn’t lift the tracks either. Next, he went to Ann Jones Inn, took her and her family prisoner and then he woke up Stanistreet, not to ask him to stop the train but to provide him with people and equipment to pull up the tracks. So, was Kelly just confused and out of his mind, or more likely, trying to rewrite history and put his own actions in a less unfavourable light by deliberately lying?

Kellys loose grip on reality becomes more obvious a bit further on with this bizarre and readily identified fabrication about Curnow, who tricked Kelly into letting him go, and who then in great fear for his life ran down the line and warned the approaching train about the damaged rail ahead:

“Then I let a man go to stop the train about a mile below the railway station and opposite the police barracks and to tell them that they were in the barracks…… The reason I differed from the first plan is I wanted the man that stopped the train to have the reward, as I heard it was to be done away with in three days.”

An even more unhinged claim is this one:

“When the train stopped at the station I was opposite on horseback. I jumped off in a hurry to take possession of the train when a bolt broke in my armour which necessitated need to repair it. This gave the police time to get in front of the hotel and fire into the people

Kelly is claiming that it was HIS idea to send Curnow down the track so he could claim a reward, and that if a bolt hadn’t broken on his armour he would have taken “possession of the train” – is there anyone who doesn’t agree with me that this is completely delusional bullshit?

In the other Condemned Cell letters there are many more examples of Kelly trying to rewrite history and making claims that don’t match reality. One place they can be read is here.

There’s always been a narrative that these last unhinged rants of Ned Kellys were the result of the extreme emotional and physical stress he was under at the time. He was still recovering from the many injuries he sustained at Glenrowan, and of course waiting alone on Death Row to be hanged would likely unhinge even the sanest murderer. There is also the somewhat contradictory narrative, also advanced by Kelly supporters, that he was actually remarkably composed, that he had bravely accepted his fate and faced death calmly, thus demonstrating his heroic greatness. I suppose even mad people can face death calmly.

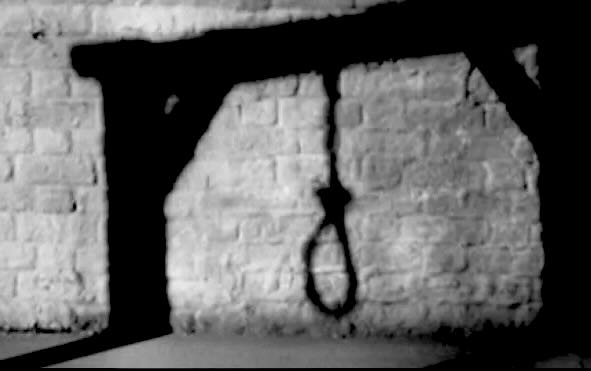

At the end though, whatever one believes about who he was and what state of mind he was in for those last days of his young troubled and violent life, his execution by hanging was a barbaric and inhumane way to end it. Thankfully, in most civilised countries mad people are not executed any more.

Your comments that the plan was clearly mad, do we actually know what his plan was? Various theories and possibilities. Let’s discount the Republic and what is left,

bank robberies perhaps…the kidnapping of police to trade for his mother?. He may not have been able to take on the entire force but at the beginning of the Siege he could well have taken on the small numbers had he not let Curnow go. The letters certainly have several factual errors that much we can be sure of. Was he mad in the way of an insane man? I don’t know, was he pushed to the brink from being on the run for so long? Thinking of the final days, I wonder why the Governor wanted his son to meet Ned Kelly? Doesn’t that seem to go against the idea that Ned was a cold hearted killer and an insane one at that. Similarly with Bracken saving his life at Glenrowan. Dave.

Hi Dave, what you’re referring to really is what plan Kelly might have made once his Glenrowan ‘plan’ had been carried out. Its his Glenrowan plan to wreck the train and murder police that was described as ‘mad’….but thats about all he seemed to have really thought about. He doesnt seem to have made a clear plan about what to do next – was it take hostages and rescue his mother , or rob banks …it was never clear, which of course only adds to the impression he was mad and obsessed with the train wreck and the police and black tracker murders, and hadnt done what a sane person would do and have a well thought out plan for what was going to happen next. I suppose that lends support to the idea he didn’t expect to succeed and was just planning to end it all, to go down and take as many as he could with him…

Ive mentioned this before but its a theme I believe people in general have missed, this idea that Kelly was a work-in-progress. His criminality evolved over ten years from petty to major, and so I think did his madness, from larrikin irresponsibility to reckless disregard for everything but his own all-consuming obsessional vendetta against police. People who ask how could he be a mass killer when he saved a boy from drowning – they dont get it! Being a nice boy doesnt mean a person cant become a dangerous adult, and being sane at 12 doesnt preclude psychiatric illness at 18.

As for the Governor wanting his son to meet Ned Kelly – all kinds of reasons are possible, including the Governor being wrong about the kind of man he thought Ned Kelly was.

From all my readings on the Kelly era, it is relatively clear that Ned Kelly was mentally unstable. There are indications of schizophrenia, and possibly insanity, when one considers all the facts. The Stringybark Creek murders is a classic case of a man not thinking logically. Common sense, if used, would have resulted in the gang moving further into the bush to avoid confrontation with the police. Why did Kelly choose such an aggressive approach? His actions were not logical in any sense, and set in motion a chain of events that ended with the total destruction of the entire gang.

The Glenrowan matter, could only be described as a debacle from top to bottom, with little or no planning being evident. One could write a great deal, pointing out the complete lack of any semblance of a plan that may have been formulated by Ned Kelly. What occurred at Glenrowan was a complete shambles on the part of Kelly. Nothing he thought would happen, happened. His behaviours were illogical, ill thought through, and resulted in the death of three of the gang members, and eventually his own hanging.

The letter’s he dictated in gaol were all fictional nonsense, and we know, he was a liar, but not a very good one, as so much of his ramblings were known to be made up nonsense.

We will never know if insanity played a part in the events that unfolded, but in my considered view, one could make out a fairly good case to support that view.

‘[Wild Wright] told me on one occasion that I mentioned the matter to him that he would not betray Ned Kelly for all the money in Australia. He also several times said to me “Ned Kelly is mad.” I pressed him to explain what he meant but he only emphatically reiterated his statement.’ – Thomas McIntyre

“Several times”….and thats from a supporter !

Heres another comment thats always interpreted as being complementary, and I think they were intended to be complementary when uttered, but I wonder if in quoting them, Fitzpatrick wasnt making a mockery of Harty . “ Ned Kelly is the best bloody man that has been in Benalla. I would fight up to my knees in blood for him….I would take his word sooner than another mans oath”

These words are way over the top, way out of touch with the reality of who Kelly was, but could Fitzpatrick have been quoting them to show how utterly fanatical and crazy Kellys supporters were? Just a thought that crosses my mind every now and then….

Glenrowan was meant to be a sequel to Stringybark Creek. Ambush the police, kill them all, don’t let any escape this time. What else is there to understand?

The armour? That’s not hard either.

As I argue in Nabbing Ned Kelly, they already had at least one suit of bullet proof armour and they had the ability to make more. Of course they would incorporate it into their plans.

Ned was paranoid about being poisoned.

At Stringybark Creek, he made McIntyre sample the food before eating it himself, even though McIntyre had had no opportunity to tamper with it. He did the same thing at Faithfull’s Creek Station and again during the Euroa bank robbery. When Susy Scott brought him water, he made her drink some of it before he did.

I could understand him being worried, and even paranoid, about people trying to kill him, but this seems to be beyond anything rational. It suggests that he was not of sound mind.

Great observation. He was certainly paranoid – I think we can say that for sure.

The following embodies the major portion of a conversation between an Age reporter and Ned Kelly in the Beechworth gaol: —

REPORTER : You have said you were harshly and unjustly treated by the police, and that you were hounded down by them. Can you explain what you mean?

KELLY: Yes. I do not pretend that I have led a blameless life, or that one fault justifies another, but the public in judging a case like mine should remember that the darkest life may have a bright side, and that after the worst has been said against a man, he may, if he is heard, tell a story in his own rough way that will perhaps lead them to mitigate the harshness of their thoughts against him, and find as many excuses for him as he would plead for himself. For my own part I do not care one straw about my life now for the result of the trial. I know very well from the stories I have been told of how I am spoken of, that the public at large execrate my name; the newspapers cannot speak of me with that patient toleration generally extended to men awaiting trial, and who are assumed according to the boast of British justice, to be innocent until they are proved to be guilty; but I do not mind, for I have outlived that care that curries public favour or dreads the public frown. Let the hand of the law strike me down if it will, but I ask that my story might be heard and considered; not that I wish to avert any decree the law may deem necessary to vindicate justice or win a word of pity from anyone. If my life teaches the public that men are made mad by bad treatment, and if the police are taught that they may not exasperate to madness men they persecute and ill-treat, my life will not be entirely thrown away. People who live in large towns have no idea of the tyrannical conduct of the police in country places far removed from Court. They have no idea of the harsh and overbearing manner in which they execute their duty, or how they neglect their duty and abuse their powers.

“INTERVIEW WITH NED KELLY. (1880, August 14). The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), p. 2 (The Mercury Supplement). Retrieved June 9, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article8986711”

Now read the following Condemned Cell Correspondence dated the 1st November 1880

Ned Kelly

November 1, 1880

I do not pretend that I have led a blameless life, or that one fault justified another, but the public judging a case like mine should remember, that the darkest life may have a bright side, and that after the worst has been said against a man, he may, if he is heard, tell a story in his own rough way, that will perhaps lead them to intimate the harshness of their thoughts against him, and find as many excuses for him as he would plead for himself.

For my own part, I do not care one straw about my life now or for the result of the trial. I know very well from the stories I have been told of how I am spoken of, that the public at large execrate my name; the newspapers cannot speak of me with that patient toleration, generally extended to men awaiting trial, and who are assumed, according to the boast of British justice, to be innocent until they are proven to be guilty; but I don’t mind, for I have outlived the care that curries public favour or dreads the public frown.

Let the hand of the law strike me down if it will, but I ask that my story be heard and considered; not that I wish to avert any decree the law may deem necessary to vindicate justice, or win a word of pity from anyone.

If my lips teach the public that men are made mad by bad treatment, and if the police are taught that they may not exasperate to madness men they persecute and ill-treat, my life will not entirely be thrown away. People who live in large towns have no idea of the tyrannical conduct of the police in their country places, far removed from court; they have no idea of the harsh and overbearing manner, in which they execute their duty, or how they neglect their duty and abuse their powers.

Edward Kelly.

Word for word a verbatim report. So why was a previous newspaper report touted as correspondence written by Kelly from a Condemned Cell. Obviously an orchestrated attempt by someone, obviously not Ned Kelly, to mount a campaign to garner sympathy for the man sentenced to death for the murder of Constable Thomas Lonigan.

Michael

Hi Michael, there was no Condemned Cell letter of 1 November 1880. The first of Kelly’s three condemned cell letters is 3 November. I discussed this in my Republic Myth book, downloadable from the top of this web page. Here is the first paragraph of what I wrote on p. 51:

The manufactured “interview” with Kelly in the Beechworth gaol:

On 9 August 1880, the Age published one of Kelly’s several versions of his story of the events leading to his outlawry, claimed to be from a reporter’s interview in the Beechworth gaol, but in fact composed by his solicitor, David Gaunson.476

The Advertiser later savaged Gaunson, writing that he had “used his privilege as an attorney to put into the mouth of the illiterate outlaw [a] rigmarole of sentimental absurdity”.477

The first four paragraphs are often wrongly claimed by Kelly enthusiasts to be a “Condemned Cell letter” of 1 November 1880.478

The little reference numbers in that are to the footnotes on p. 51.