“I would rather have my eyes gouged out than read this book”

Well known Kelly sympathiser and conspiracy theorist demonstrating his unquenchable thirst for knowledge and the truth.His FB page is dedicated to discrediting a Kelly book he admits to having never read!

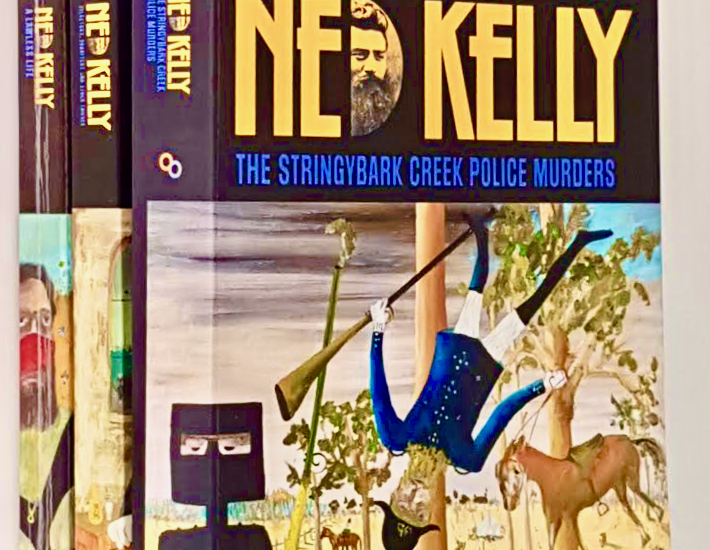

Writing this review of Doug Morrissey’s third and final book of the planned trilogy about the Kelly outbreak is proving to be an awkward dilemma, because even though in general I agree with most of what he has written, and with what he is trying to do in this book, there is so much about this volume that annoys and frustrates me that I am tempted to write it off altogether. However, for all its many faults this volume has at least one redeeming feature: the unadvertised fact that its actually two books in one, the second and I think probably more important book being the entire manuscript of Constable Thomas McIntyres memoir, ‘A True narrative of the Kelly Gang’ written in 1900. Even though this memoir is accessible through the Victoria police website, as far as I am aware it’s never been formally published before.

So, writing off the entire book would be a mistake, because my concerns are mostly the concerns of a picky Kelly history nerd, and an ordinary reader may well not be worried in the slightest about the things that infuriate me. However, I am going to mention them first, so I can finish on a positive note.

To start with, many people who read the first two books in the series complained about the failure to include references back to the original sources. Morrissey made reference to his doctoral thesis – which is not widely available – and complained that there had been so much re-arranging and mixing and disruption of files at the Public Records Office that his original references were no longer valid – and he didn’t go searching for them again. Many people expressed a hope that this latest volume would include them – but again, there are none. Even worse, there isn’t even an Index, something which the previous two volumes included, so he hasn’t even bothered to help readers find things they want to refer to in his own book. Readers are simply expected to take Morrissey’s word for it that where text appears in italics, it’s a direct quote from a document he once viewed at the PROV or a library or somewhere, it’s not taken out of context, its quoted accurately, and nobody needs to bother themselves with going back to the source and reading if for themselves. However, as many of us know, the reality is that in the Kelly community, quotations are too often misquotes, are taken out of context or are incomplete and used to bolster a misrepresentation. To be clear I am not accusing Morrissey of deliberately doing any of that – but as he would be very well aware, this tiny space in Australian history is highly contested and if he wants to elbow out of the way the Kelly myth-makers and conspiracy theorists I don’t think it’s good enough for him to declare that the sources support his version and not theirs, take it or leave it. People who already agree with him will take it and those who don’t will leave it, because without providing a reference to the source of his claims that people can check for themselves the debate reduces to one person’s opinion against another’s. Without verifiable references a claim loses much of its authority: a great pity, in my view. Tracking down references is unglamorous tedious and frustrating hard work but he should have made the effort. To me, this failure reflects a lack of respect for the readership.

Next, it seems if anybody proof read this script, they did a very sloppy job of it indeed and left a legion of grammar and punctuation and spelling mistakes all through the book. I’ve never before read a book that is so full of such obvious blunders : I noted “too” instead of “to”, “boroughs” instead of “boughs”, ‘trail’ instead of ‘trial’, ‘prostate’ instead of ‘prostrate’, ‘gaol’ spelled ‘goal’ in at least four places – and an enormous number of annoying and bizarre punctuation errors, most of which were full stops in the wrong place, like this example from p3, which isn’t actually a sentence:

“It is interesting to note that when Dan and his cousin were taken into custody for the Winton disturbance.”

The next line is obviously the second half of that sentence which shouldn’t have ended where it did “It was Ned who arranged the arrest and said he would deliver the boys to Fitzpatrick and only Fitzpatrick…“. Here’s another sentence that’s been chopped into two by a full stop that shouldn’t be there: “So thorough were the gang in obliterating the camp that when the Mansfield rescue party arrived at the camp a day later. All they found were the bodies of Lonigan and Scanlan, a scorched patch of earth where the tent had stood, a single tin plate and Kennedys blood-stained notebook with pages torn out”

These ridiculous and disruptive punctuation mistakes are frequent and found throughout the book, and in the McIntyre text as well, though obviously are not what the author would have written but must be the fault of the editing software or spell-checker. They ought to have been corrected by a human reviewer. They indicate incredible carelessness by the Publisher.

So now we come to the content of this strangely disjointed book which begins with an Introduction written by Leo Kennedy, great grandson of murdered policeman Michael Kennedy, and finishes with five loosely relevant Appendices, including an interesting piece about Kennedys gold watch, and a poem. The rest of the book is divided into three parts, the first being about the lead up to the ambush at SBC, the second part being about the attack itself and the aftermath, and the third part is McIntyre’s Memoir which occupies the entire second half of the 400-page book.

The only thing I am going to say about McIntyre’s memoir is that Morrissey’s attempts to tidy up the structure of sentences and ‘make McIntyre’s 19th century prose easily readable’ was another stuff up, partly because the same punctuation gremlin affected this part of the book just as it had all the rest of it, but also because Morrissey’s meddling made it LESS readable in several places where I checked his version against the one you can read on the Vic Pol Website. I would have much preferred to know that what I was reading was exactly what McIntyre wrote rather than something that had been fiddled with by Morrissey.

In his discussion of the lead up to the murders Morrissey makes reference to the so-called Fitzpatrick incident and writes that “Fitzpatrick was a regular visitor , drinking and carousing with the family while conducting a romance with young Kate, so he thought he could combine a visit to see his girlfriend with the arrest of her brother Dan.” At another point, Morrissey claims Ned Kelly and Fitzpatrick were ‘larrikin drinking buddies on a pub crawl in Benalla’ and he then goes on to wrongly describe what happened when Ned Kelly attempted to escape police custody, providing the narrative that lends support to the mythology rather than the facts. (The myth is that Kelly ran off to try to escape the humiliation of being handcuffed as he was walked from the lock-up to the courthouse but as Kellys own account in the August 1880 ‘Interview’ reveals, handcuffs were not contemplated until after he was recaptured in the bootmakers shop, after he had tried, on impulse out on the street to make a run for it. The important point Morrissey and all other Kelly biographers missed is that the myth contains the lie that police were trying to humiliate Kelly, and that’s what provoked his resistance when in fact police offered him the respect of the chance to walk freely to the Courthouse, but he took advantage of that and made a rash and foolish attempt to escape. This act of delinquent showing off was what resulted in the police deciding to handcuff him when he was recaptured in the bootmakers shop.)

For some inexplicable reason, in describing Fitzpatricks relationships with Kelly clan members in this way, Morrissey seems to have accepted the unfounded Kelly mythology about Fitzpatrick that he was a womaniser and a drunk. His only attempt in this book to justify his claim about Fitzpatrick conducting some sort of ‘romance’ with Kate Kelly is this rhetorical question on page 8 asked in the context of an observation recorded by Fitzpatrick after the melee in which he was shot. Fitzpatrick said that Kate ‘sat down and cried’: “Why else would Kate cry if she didn’t have some affection for Fitzpatrick?’ Morrissey asks. There are of course many possible explanations of why she cried – she was only 14 years old – but to suggest that her tears support the unlikely idea that she was Fitzpatrick’s ‘girlfriend’ is absurd. Equally absurd is Morrisseys claim that because its recorded that Kelly and Fitzpatrick were in a pub having a drink they must have been on a ‘pub crawl’. The circumstances around this incident are not explained anywhere by anyone from the time, so for Morrissey to claim they were on a ‘pub crawl’ is yet more unreferenced speculation.

Part one also contains brief but valuable biographies of each of the murdered police and of McIntyre, the sole survivor. Morrissey may not have realised it but his account of Scanlans police record provides a very good reason to reject his earlier characterisation of Fitzpatrick as a drunk. Here, he makes note of Scanlan’s police record which included several reprimands and fines for drunkenness, the last of which was in 1874. In 1877, his conduct was recorded as ‘much improved’ – indicating Police hierarchy awareness and concern about drunkenness in the ranks. In contrast to Scanlans record, the absence of even one such comment in Fitzpatrick’s police record is therefore significant, and seriously undermines Morrissey’s and Kelly clan claims about Constable Fitzpatrick being a policeman struggling with drink. There is in fact no evidence that he was.

PART TWO TO FOLLOW IN A WEEK.

NB : I Have limited Internet access at present so responses may take a day or two to be approved and Posted.

Hi David, thanks for pointing out the myth that on 18 September 1877 Kelly ran off in Banala to try to escape the humiliation of being handcuffed as he was walked from the lock-up to the courthouse charged with drunkenness, repeated by so many writers. I was surprised to see that a fairly accurate summary was provided long ago by Kenneally.

Here is what Kenneally 1929 [9th ed, 1980, p. 26] said – “During a visit to Benalla, in 1877, he was arrested on charges of being drunk and of having ridden his horse across the footpath. … As he was being brought next morning from the lock-up to the Court House, he escaped from the constable who was in charge of him, and took refuge in King’s bootmakers shop. He was pursued by the Sergeant and three constables, who, with the assistance of the bootmaker, tried to handcuff him. A fierce fight ensued …, and the struggle was only terminated by the arrival of Mr. Wm. McInness, J.P., a local flour miller, who rebuked the police in strong terms for their brutality and cowardly violence. Satisfied that he had now beaten the four police and the bootmaker, Ned Kelly held out his hands to Mr. McGuiness, and invited the latter to put the handcuffs on him.”

This was the morning after Fitzpatrick (in Cookson 1911, p. 94) “had arrested Ned Kelly for drunkenness and had looked after him in the lockup and treated him kindly.”

As you point out, four police did escort Kelly to the courthouse – as he was a known larrikin – but he was walked without handcuffs and therefore with dignity intact. No-one suggested handcuffing him. It was entirely his own stupid decision to run off that led to the bootmaker’s shop brawl and subsequent handcuffing, that turned a charge of drunkenness into a much more serious incident.

Bit harsh.

What exactly?

I think that was Mark Perrys comment on the Book review. Part Two is nearly ready to go up.

More on the Benalla bootmaker’s brawl, which has proved surprisingly interesting:

G.W. Hall (Outlaws of the Wombat Ranges, February 1879) wrote that he had a source who spoke to some or all of the Kelly gang in the bush shortly after the Jerilderie raid. His account is presumably what that source told him, as he would likely not have had access to a copy of the Euroa or Jerilderie letters themselves. (You can download a free PDF copy of Hall’s book from this link, https://ironicon.com.au/gw-hall-the-kelly-gang-1879.htm)

On p. 41 Hall wrote, “It is said that Ned Kelly, a few years since, being on a spree in Benalla, was one evening rather disorderly and noisy, whereupon three constables, one being Lonigan, attempted to arrest him. Kelly, however, placing his back to a wall, set them at defiance, knocking them down like ninepins as fast as they came up. An acquaintance, a butcher, happening to be passing, and taking in the situation at a glance, sensibly recommended Kelly to go with the police quietly, or the affair might take a more serious turn for him. He at once said he would let the friend “snap the handcuffs on him”, but swore he would never let the police have the satisfaction of doing so. The irons being adjusted on these conditions, Kelly went quietly with the constables towards the lock-up; but the story goes on to say, the police, when they got him safe out of sight on the road, commenced to handle him very roughly, and at last knocked him down. The most improbable part of the tale, though within the bounds of credibility, comes last – namely, that while he lay on the ground manacled, Lonigan deliberately jumped on him, breaking three of his ribs, which caused him to be laid up for nine months. It is further said, that after Kelly was thus maltreated (if he was so), he exclaimed, “Well, Lonigan, I never shot a man yet; but if ever I do, so help me G—, you will be the first!”

Hall got the story totally wrong. The seriously drunken Kelly was riding his horse on a footpath when arrested in the afternoon by Fitzpatrick, taken to the lockup and kept overnight. It was the next day when Kelly made a run for it while being escorted unmanacled to Court. He ran into a Benalla bookmaker’s shop, probably thinking to escape through a rear door. However, the police chased him in there and he fought until they were able to subdue him. It was during that struggle that Kelly punched Fitzpatrick and Lonigan blackballed him. Wm McInnes, miller and JP, came in and induced Kelly to surrender. Kelly, ever the larrikin, consented to be handcuffed by McInnes but not by the police. He was then escorted straight to Court accompanied by McInnes. Hall’s version is quite wide of the facts. Indeed, Ian Jones (Short Life 2008: 438) described Hall’s as “a highly inaccurate version of the brawl”.

We see this when we compare it with what Kelly himself said at the time.

In the Euroa letter of December 1878 p. 12-13, Kelly says of Lonigan that “him Fitzpatrick Sergeant Whelan Constable O’Day & King the bootmaker once tried to handcuff me at Benalla and when they could not Fitzpatrick tried to choke me. Lonigan caught me by the privates and would have killed me but was not able. Mr. McInnes came up and I allowed him to put the handcuffs on when the Police were bested.”

In the Jerilderie letter of January 1879 p. 33-36 Kelly says “it happened to be Lonigan the man who in company with Sergeant Whelan Fitzpatrick & King the Bootmaker and Constable ODay that tried to put a pair of hand-cuffs on me in Benalla but could not & had to allow McInnis the miller to put them on … I was fined two pounds for hitting Fitzpatrick & two pounds for not allowing five curs like Sergeant Whelan ODay Fitzpatrick King & Lonigan who caught me by the privates and would have sent me to Kingdom come only I was not ready… Fitzpatrick is the only one I hit out of the five in Benalla; … I had a pairs of arms & bunch of fives on the end of them … and Fitzpatrick knew the weight of one of them only too well, as it run against him once in Benalla…”.

Note that both of Kelly’s versions omit that he had already spent the night in the lockup. This becomes clear in the tale he told in 1880, written by his solicitor Gaunson and printed in The Age 9 August 1880 p. 3 under the guides of an interview with a ‘reporter’:

“Some time ago I had been drinking, and I think I was drugged, and I was arrested for some trifling offence — riding over a footpath, I believe— and lodged in the lock-up. On the following day, when I was taken out of the lock-up, and, still dazed, I escaped and was pursued by the police. I took refuge in a shoemaker’s shop, and four constables soon came in after me. They, assisted by the owner of the shop, tried to put the handcuffs on me, but failed. In the struggle … Lonigan seized me in … a cruel … and disgusting manner ….. While the struggle was still going on a miller came in, and, seeing how I was being ill-treated, said the police should be ashamed of themselves, and he endeavored to pacify them and induce me to be handcuffed. I allowed this man to put the handcuffs on me, though I refused to submit to the police. … In the course of this attempted arrest Fitzpatrick endeavored to catch hold of me by the foot, and in the struggle he tore the sole and heel of my boot clean off. With one well-directed blow I sent him sprawling against the wall, and the staggering blow I then gave him partly accounts to me for his subsequent conduct towards my family and myself.”

This contains another piece of nonsense by Kelly. It was barely a month after that incident – DATE – that he persuaded his brother Dan, and his cousins Jack and Tom Lloyd, wanted for assault and damage at a Winton store, to surrender themselves to Fitzpatrick in Benalla. That fact gives more credibility to Fitzpatrick’s statement in Cookson 1911, p. 94 – “I had arrested Ned Kelly for drunkenness and had looked after him in the lockup and treated him kindly.” Despite the bookmaker’s shop brawl, Kelly recognised that Fitzpatrick played fair – the same character trait that resulted in two petitions by respectable citizens of Lancefield to have him reinstated in the police force after his 1881 dismissal.

David,

Michael Piggott agrees with your review thus far. Doug thinks it’s time to bury Ned;

http://honesthistory.net.au/wp/piggott-michael-an-out-of-shape-homage-to-ned-kellys-murdered-victims-at-stringybark-creek/

https://quadrant.org.au/magazine/2017/05/time-bury-ned-kelly-myth/

Cam West

Thanks for that Link Cam. He has written a much better review than I could, and I agree with him entirely. The more I think about it the more I think Morrissey had run out of ideas for the third book of his trilogy and scrambled about finding bits and pieces to string together to make it.

Even more on the Benalla bootmaker’s shop brawl:

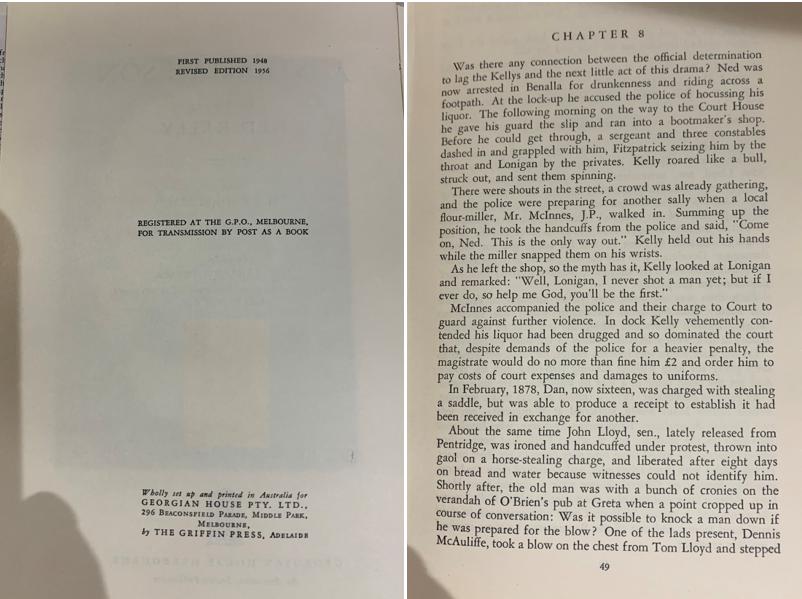

Max Brown in the first edition of his “Australian Son” (1948: 51) gave what is emerging as the most accurate summary of the Benalla fracas, regardless of his conspiracy theory that the police were unreasonably out to get the Kellys, which David has well debunked in several places on this blog. Brown wrote,

“Ned was now arrested in Benalla for being drunk and riding across a footpath. At the lock-up he accused the police of hocussing his liquor. The following morning on the way to the Court House he gave his guard the slip and ran into a bootmaker’s shop. Before he could get through, a sergeant and three constables dashed in and grappled with him, Fitzpatrick seizing him by the throat and Lonigan by the privates. Kelly roared like a bull, truck out, and sent them spinning. There were shouts in the street… and the police were preparing for another sally when a local flour miller, Mr. McInnes, J.P., walked in. Summing up the position, he took the handcuffs from the police and said, “Come on, Ned. This is the only way out.” Kelly held out his hands while the miller snapped them on his wrists. As he left the shop, so themyth has it, Kelly looked at Lonigan and remarked: “ Well, Lonigan, I never shot a man yet; but if I ever do, so help me God, you’ll be the first.” McInnes accompanied the police and their charge to Court to guard against further violence.”

Brown gives the threat to Lonigan first found in Hall; but he accepts none of Hall’s tale of the police assaulting Kelly on the way to Court after the fracas. That is more reminiscent of Kelly’s gross lying exaggerations of events in the Euroa and Jerilderie letters; and Brown’s version sticks to the known facts without creative additions. It is consistent with Kelly’s remarks in his two letters, and with his August 1880 statement to Gaunson.

That all changed for the worse when Brown revised his book in 1981. On p. 40 of the Australian Classics printing, he wrote that Kelly and the police party “were crossing the street, when – in accordance with the police practice of getting the new chum to do the dirty work – Fitzpatrick set out to handcuff the prisoner. Kelly hit out and ran back into a bootmaker’s shop, only to find, before he knew it, that Fitzpatrick had him by the throat and Lonigan by the testicles. He hit out again, and the police were preparing for another sally when the local flour miller, Mr. McInnes, J.P., entered the shop,” etc. as before.

Why did Brown destroy his factual 1948 presentation of the fracas with the 1981 revision’s fanciful nonsense in direct contradiction with Kelly’s own statements, and inventing some imaginary police malpractice procedure? It seems his antagonism to Fitzpatrick was behind it. His last 2003 p. 47 revision is even worse. He squeezes in half a sentence of abuse about Fitzpatrick from the Jerilderie letter, and has McInnes appear when the police “were preparing for a third sally”, rather than the second final sally of his previous versions. It looks like Brown is indulging in the progressive fictionalisation of the Kelly story, climbing progressively further away from his initial accurate 1948 presentation that matched what Kelly actually said. Take 10 points off Brown for each of his revisions. That alone marks his book down to 80/100 for knowingly presenting pure BS as history.

Frank Clune, “Ned Kelly” (1954), did his own bit to stuff things up. Brown’s 1948 edition is listed in Clune’s bibliography, so Clune must take some of the blame for helping shift the bootmaker’s brawl into the form it is most often presented today. His book may also have influenced Brown’s (1981 and later revisionism.

Clune p. 123 says, “Walking from the lockup to the Court, escorted by the four police, Ned was going quietly when Fitzpatrick, on a silly impulse, decided to put a pair of handcuffs on the prisoner, to bring him before the magistrates manacled in order to create the impression that he was a dangerous man. … Ned punched Fitzpatrick on the jaw, wrenched himself free, and ran across the street, with the four police in pursuit.” In Clune, the quiet walk to Court was ruined by the evil Fitzpatrick, acting on a “silly impulse” to handcuff Ned, and so causing the fracas. The blame has shifted entirely to the police, with Ned an innocent victim of police maltreatment – the same idea in Brown’s 1981 version. Again, this is completely at odds with what Kelly himself said happened. These “historians” seem to be on drugs at times.

To conclude this post, we can note another misstatement from Ned. Regardless that a brawl took place involving four police and a bootmaker, in which a number of blows were clearly struck, Kelly wrote in the Jerilderie letter that “Fitzpatrick was the only one of the five that I hit”. He loved a good story, that Kelly, but he is as unreliable as a stopped clock. Nevertheless his three statements all support Kenneally’s 1929 and Brown’s 1948 versions, and scuttle Clune’s 1954 version and all of Brown’s subsequent revised versions.

I wonder what Ian Jones made of it all? Which of these two divergent presentations will the famous Kelly biographer side up with? The factual one presented by Kenneally and in Brown 1948, consistent with Kelly’s own statements; or the fanciful one presented by Clune and in Brown’s later editions? I can’t wait to find out and post about it…

That expose of the evolution of Kelly myth is an extraordinary bit of analysis Stuart, and many thanks for writing it. When I realised the popular version was contradicted by what Kelly himself said I didn’t think to try to trace the origins of the myth but you’ve done it brilliantly!

Brown’s decision to elaborate the orginal accurate telling and turn the whole thing into a piece of anti police Kelly propaganda has to be condemned.

I haven’t peeked but I suspect you’ll find Jones perpetuated the myth.

Hi David, it was your highlighting in the lead article that “handcuffs were not contemplated until after Kelly was recaptured” in the Benalla bootmaker’s shop brawl that led down this rabbit hole of historical distortion. It is fascinating that we have three clear statements by Kelly about what happened, but a bunch of so-called historians including best-sellers have gone off with no other evidence at all and written something completely different. Brown did a 1956 revised edition after his accurate 1948 first edition version of the brawl, and before his 1981 fairy story version. I don’t have a 1956 copy, but it would be nice to know if he was still with the accurate 1948 story in 1956, or if he began propagating nonsense 25 years earlier than his 1981 edition.

I was about to check Jones again (yes, peeking ahead is OK!) when I thought it would be good to see what Professor John Molony said in his 1980 “I am Ned Kelly”. Surprise – it wasn’t what Ned said at all. On p. 92 he decided it was Fitzpatrick’s decision to handcuff Ned on the walk to Court: “Ned resented such proceedings …and fled into a bootmaker‘s shop…”. The Professor failed that simple research assignment by ignoring Kelly’s own statements about what happened, and should be posthumously demoted to ANU tea-boy. McMenomy also erred in his “Authentic Illustrate d History” (2001 edn, 65) in saying, “While the four policemen and their hung-over prisoner crossed the corner opposite the courthouse, Fitzpatrick tried to handcuff Kelly.” No: read Kelly’s 1880 statement and try again, thank you.

Corfield’s Kelly Encyclopaedia p. 266 excitedly tells us that “Kelly was briefly in trouble with the law after having a drink with … Fitzpatrick in Benalla. … Fitzpatrick tried to handcuff Ned Kelly when taking him from the police lockup to the Benalla Court House.” No: another historian who hasn’t read what Kelly said happened, and it wasn’t that. Neither is there a shred of evidence that Fitzpatrick had had a drink with Kelly on the afternoon of the 17th. That is impossible: Fitzpatrick’s work hours preclude it. He was on duty, arrested Kelly in the afternoon and took him to the lock up. There were only 5 police stationed at Benalla, and there is no evidence anywhere for Fitzpatrick ever drinking on duty except for the famous glass of lemonade and brandy on the way to Greta on a hot afternoon in April 1878. Kelly was so bat-faced in Benalla that he blamed the police for hocussing his drink; a throw-away line in his August 1880 tale on the well-worn track that nothing was ever his fault. Clune “Ned Kelly” (1954: 122-3) saw it quite differently: Kelly “rode into Benalla Town for a spree. … He was dead drunk, blind drunk, unconscious drunk”. Yep, it really was all Ned’s fault, as usual. And he blamed everyone but himself, as usual.

Two recent blockbuster size books also illustrate the two different accounts of the brawl. Keiza’s “Mrs Kelly” p. 194 give the correct version, consistent with Kelly’s statements, that the unmanacled Kelly broke free from the police guard on the way to court and rans into the bootmaker’s shop where the brawl ensued. Brown’s 1948 first edition presents that version in an effective and much shorter way. By contrast, FitzSimon’s “Ned Kelly” p. 118-9 gives the most ridiculously wordy presentation of the second version I’ve seen, that en route to Court “the trouble starts when Fitzpatrick suggests they put ‘Darbies’ on Ned”, and spends two full pages on an elaborate fictionalised “description” of the ensuring brawl in the bootmaker’s shop. “Historical fiction” is the genre those two pages belong to, and might as well have been based on an afternoon watching MMA on TV in a pub with a crowd of oiks. I’ll get to Jones’ version tonight.

As noted above, Brown changed his tune dramatically in his presentation of the Benalla bootmaker’s shop brawl, from his factual 1948 account to his fancy-filled 1981 revision. Today I came across a copy of his 1956 revision, and as we can see from the attached picture, he repeated the 1948 factual version in 1956. So at some point between 1956 and the 1981 revision, he threw facts out the window in respect of this incident and wrote a lot of rubbish about it.

Attachment

Its really a great bit of forensic myth-tackling that youve done there Stuart, showing the actual timeline of its invention.

The reason there are so few responses to this review and these comments I think must be because Kelly people like to collect books and exhibit them at Show and Tell Facebook pages, but they hardly ever read them.

Yes, collecting is about status through ownership, and you only get the status by showing off your status objects. I like to have the latest edition of a book if there has been more than one edition, as you can see where the author has gone over time, and a cheap paperback copy is fine. Having books is useful and reading both the text, reference notes and bibliography is essential for any serious historical work.

Benalla bootmaker’s brawl, final instalment: What did Ian Jones say in “Short Life”, 2008: 124-5?

It may come as no surprise to readers of this blog to find that Jones, after more than 40 years of reading, writing and speaking about Kelly and the outbreak, and getting much of it wrong, got this wrong too. He wrote:

“When it was time to bring Ned from the lock-up to … the Court …, in spite of the four-man escort, Fitzpatrick suggested that his prisoner should be handcuffed. This odd behaviour by his ‘friend’ must have suggested to Ned that Fitzpatrick had been involved in drugging his drink. … He broke away and charged around the corner … into a bootmaker’s shop…. In a widely quoted piece of apocrypha, Ned is supposed to have roared, ”Well, Lonigan, I never shot a man yet; but if I ever do, so help me God, you’ll be the first!” [McInness J.P. then handcuffed Kelly.] After this supreme gesture of contempt for his police enemies and of respect for justice, Ned accompanied Maginness across the street to the court house to stand his trial.”

Jones gives the fiction that Fitzpatrick initiated the fracas by seeking to handcuff Kelly en route to court, against Kelly’s own statements to the contrary. Why would he do this? We need to check his notes, on p. 438.

Jones’ source for the story that Fitzpatrick suggested handcuffing Ned turns out to be Clune (1948: 123), which I debunked above from Kelly’s own statements, including the key one from August 1880 that is also listed in Jones’ notes and directly contradicts both Clune’s and Jones’ accounts. Worse, Jones hypothesised that Clune’s story of Fitzpatrick suggesting handcuffing Kelly on the way to court was “possibly based on a missing report by Sergeant Whelan”. This is outright garbage.

Clune’s reference note for his description of the bootmaker’s brawl says nothing about Fitzpatrick suggesting that. The only thing Clune said in his notes on p. 347 is, “The fines imposed on him [Kelly] are recorded in [the Royal Commission report] and in a report by Sergeant Whelan in the Crown Law Office Papers, Archives, Public Library, Melbourne”. To be clear, it is only the fines that Clune sourced to a report by Whelan, nothing else. The report of Whelan is not missing. It is now filed as VRPS 4969, Unit 1, Item 29 in the VPRO (available online). The report says exactly what Clune said it says: the amounts Kelly was fined as a result of that incident, and nothing more about it. Jones invented an imaginary report to explain a fictional story that directly contradicts Kelly’s own accounts.

There is nothing anywhere to back Jones’ speculations that there was any friendship between Kelly and Fitzpatrick, and that Kelly was telling the truth when he claimed his drink was hocussed, rather than that he had gone drinking in Benalla (which he freely admitted in the August 1880 statement) and got bat-faced. On Kelly’s threat to Lonigan, which appeared in both Hall and Brown, Jones called it “apocryphal”, but there is support for it in Gascoigne’s Royal Commission evidence, Q.9764.

Jones’ quite incorrect presentation of the Benalla bootmaker’s brawl directly contradicts Ned Kelly’s own three descriptions. Kenneally and Brown (1948 edition only) both did a much better job on this event. About the only thing Jones clearly got right was the date.

Two things: in the above I typed the reference to Clune’s Ned Kelly book as (1948: 123), but it should have been (1954: 123).

Second, the date Dan Kelly and the two Lloyd boys were persuaded by Ned to surrender themselves to Fitzpatrick over the Winton store assault was reported in the O&M on 10 October 1877, so less than a month after the bootmaker’s shop brawl of 18 September.

Postscript: another Jones peculiarity:

Another part of Jones’ Benalla brawl narrative also diverges from previous accounts with no explanation. The sequence of events in Hall 1879 is the brawl, then Kelly handcuffed, then his threat to Lonigan: “I never shot a man yet; but if ever I do, so help me G—, you will be the first!”

Brown 1948 follows the same sequence: “Kelly held out his hands while the miller snapped them on his wrists. As he left the shop, so the myth has it, Kelly looked at Lonigan and remarked: “ Well, Lonigan, I never shot a man yet;”, etc.

Kenneally 1929, however, altered the sequence. He has Kelly uttering the threat during the brawl and before the arrival of the miller: “While suffering the pangs of this terrible torture [being blackballed], Ned Kelly cried out: ‘If I ever soot an man, Lonigan,’ [etc.]. … the fight was only terminated by the arrival of McInnes ….”

Jones p. 125 follows Kenneally’s sequence: Kelly utters his threat against Lonigan during the brawl, after which the miller enters and Kelly consents to be handcuffed. His notes do not mention Hall’s other version of the day (or acknowledge Brown’s) so his narrative has adopted Kenneally’s sequence without explanation.

While Kelly’s own statements do not mention the threat to Lonigan, we do have the Royal Commission testimony of Charles Gascoigne, which may help:

9764. You knew him [Kelly] before, personally?—Yes; I had a conversation with him at one time before Fitzpatrick’s affair. I was looking for some horses, and he told me he was very sorry for what he did in Benalla; but, for all that, he would be one with Lonigan and Phil. Smith one day.

9765. What did that mean?—That he would have it out some day.

So after the brawl in Benalla, and given that Gascoigne dates the conversation “before Fitzpatrick’s affair”, Gascoigne’s conversation with Kelly was likely in early 1878, well after Kelly had turned over his brother and the two Lloyd boys to Fitzpatrick in October 1877; and focused on Lonigan, not Fitzpatrick. Clearly, Kelly did not make any secret of his loathing for Lonigan (and was there a constable Smith at Benalla at that time, who may have been involved in the brawl?).

Given this, it is more likely that Kelly’ threat was uttered after, not during the brawl, as Hall and Brown have it, and contrary to Kenneally and Jones. While that can’t be known with certainty, it was greatly remiss of Jones to have followed Kenneally against Hall on this point without providing any acknowledgement of Hall’s earlier sequence or rationale for preferring Kenneally’s sequence.

In fact, we should note some of Kenneally’s glaring errors: in the 1980 edition p. 26 he wrote that Kelly’s “father’s death from prison treatment after serving a sentence of only six months on a ‘trumped up charge’ of having a cask with meat in it in his possession, intensified his distrust in the honesty of the police of that day.” What rubbish.

Red Kelly had killed a neighbour’s calf for meat; the skin was found on his property and the meat in a cask. He was guilty as, and gaoled leniently in the Avenel lock-up, not sent to Kilmore Gaol. He was let out early, with in Ian Jones’ words (SL 208: 27) “a generous remission of more than two months”. When he got out in the first week of October 1865 he hit the grog again, drank his way through 1866 (see Jones SL 2008: 30), and died in December 1866 of alcohol-related health issues (dropsy), not from police mistreatment. Kenneally’s “Inner History” is so full of crap.

Stuart Ive just noticed another nail in the coffin of the Bennalla Brawl myth : and its Ned Kellys own words!

In the Jerilderie Letter he wrote that it was “….Whelan, Fitzpatrick and King the bootmaker…that tried to put a pair of handcuffs on me in Benalla…”

Did you see it?

(King was not part of the group walking him across the road but in the shop that Kelly ran into, trying to escape the Police, and just as Kelly also said in the Interview, it was in the Bootmakers shop that the handcuffs were brought out)

Incidentally in his annotated version of the Jerilderie letter McDermott perpetuates the myth, writing this:

“Whether through petty vindictiveness or actual fear Fitzpatrick tried to handcuff Ned for the journey. Ned shoved him violently to one side and ran into a nearby bootmakers shop”

Hi David, you’re right, that line from the JL adds additional confirmation that the attempted handcuffing was in the shop, not prior to it. And it occurred, quite reasonably, because the dumb Ned Kelly had tried to do a runner.

McDermott’s introduction to his short republishing of the JL is more mythification and marketing hype about a stupid little rant that would barely fill two columns of the O&M (as was noted by the Jerilderie school teacher at the time, re a different broadsheet paper).

It is a disgrace that any school would have the JL on a reading list at all; and that if they wanted to reference Kelly that they would use that instead of the Euroa letter which was actually printed more fully at the time; and that in any case that a school would oblige students to purchase a book when the JL text can be downloaded free from the Murrumbidgee council website, rather than needlessly costing students or parents money for Kelly’s lying, police-baiting drivel. Teachers are so often so stupid and subject- ignorant.