Sarcasm is the ‘lowest form of wit’ according to Oscar Wilde, a description that applies perfectly to the attempts at humour to be found in “A letter to Thomas” by Kelly Conspiracy Theorist and ‘Keep Ya Powder Dry’ author Alan Crichton. Crichton’s ‘letter’ is a mocking, sarcastic and cruel attack on the character of yet another honourable policeman who suffered terribly at the hands of the Kelly Gang, a man who, like most police is seen as fair game for vilification, character assassination and the promulgation of hateful lies by Kelly sympathisers all across Australia. Crichton has continued this abuse on Facebook recently, and as usual not one single Kelly sympathiser anywhere has expressed the slightest objection to it. Unsurprisingly, encouraged by the author of the atrocious ‘An Introduction to Ned Kelly’ and his toadies many sympathisers have supported it. What Crichton is telling everyone is that McIntyre was a liar and Ned Kelly was the one who told the truth about what happened at Stringybark Creek. This insidious claim feeds into the idea that Kelly was only convicted of Lonigan’s murder and hanged, because of perjury committed by McIntyre. Otherwise, the story goes, Kellys claim of killing in self-defence would have been successful and he would have been found not guilty. Yeah, right!

Crichton: “So what do you think of that Mr. McIntyre, did you lie under oath for your superiors?”

Crichton’s abuse of McIntyre is not original – it’s been going on for years. In fact, from the time of the Outbreak itself police-hating Kelly supporters, and even Kellys legal team called him a liar and a coward, doing their best to undermine the credibility of the man whose testimony would send Kelly to the Gallows. Ian Jones, the most influential of all Kelly sympathisers aggressively promoted the claim that McIntyre was a liar right to the very end – the last thing Jones ever published was “The Kellys and Beechworth” in 2014, and the title of the very last chapter of that book is “Perjury” – and yes, he was referring to McIntyre.

Before examining that specific allegation against him, that he was a liar, and the other one Mark Perrys Ming Mongs trot out at regular intervals, the claim that he was also a coward who abandoned his mates at SBC, let’s review the man’s entire life. Then, in Part 2 we will address Jones and Crichton’s demonstrably bogus assassination of McIntyres character and set the record straight.

First of all, note that like over 80% of police at the time, he was Irish. He was born in 1846, possibly in Belfast, and served in the Royal Irish Constabulary from 1863-65. Years later, in his memoir he wrote- “I never fired a shot during my service’. Then, still only 19, he migrated to Australia and was a school teacher in NSW till 1868, when he moved to Victoria:

“On the eve of your departure from us we cannot allow you to leave without officially expressing our regret that our connection is to be severed. While our judgment approves the course you took for the promotion of your interests we cannot suffer any act of ours to prejudice your actions. We take this opportunity of expressing our entire satisfaction and approval of your conduct at the School, the advancement of the children has been to us as satisfactory as surprising. We entertain a hope that you will return to us, we will hail such an event with very special pleasure. We comment you to the care of an ever kind Providence and devoutly pray wherever your lot be cast you may be Blest Prosperous and Happy”

(View this letter HERE )

He became a member of the Victoria Police in 1869, and his Service record reported him to have been “a very steady well conducted constable since he joined the force’

He worked at Swan Hill, Castlemaine, Stawell and other places and then was posted to Mansfield in 1877 where he met Sergeant Michael Kennedy. The following year Kennedy asked him to join a party of four that were about to head into the nearby hills to look for the fugitive Kelly brothers. It’s often said McIntyre was only taken because he was a good cook but there was a lot more to it than that, as evidenced by Sadleir’s comments at the Royal Commission:

- He was taken at the suggestion of Sergeant Kennedy?

—Yes, specially chosen by him. He was a zealous, conscientious man, and I could see no difference between them as to bravery and so on.

- Sergeant Kennedy must have had confidence in his courage?

—Yes.

- Is it your opinion that they acted judiciously and courageously?

—I do think it; I think he (McIntyre) acted as a brave man, and as I should have acted myself, but that is only an opinion.

At Stringybark Creek, as everyone knows, whilst standing on either side of a fire at their campsite on October 26th, 1878, McIntyre and Lonigan were surprised by the Kelly Gang who abruptly appeared out of the undergrowth and ordered the two of them to “Bail up”. McIntyre turned to face the intruders and raised his arms. Lonigan, now behind McIntyre was shot almost immediately, Ned Kelly claiming in the Jerilderie letter months later that Lonigan had ‘ran some six or seven yards to a battery of logs…and put his head up to take aim when I shot him that instant or he would have shot me’.

McIntyre, having just witnessed the brutal murder of a colleague and no doubt fearing what might happen to himself and to the other two members of the search party when they returned, must have been shocked and stressed and in immense turmoil.

“Lonigan’s body was visible from where I stood. I tried to keep myself from looking at it, lest it should unnerve me…”

He was subjected to taunts, interrogation and threats by Ned Kelly, and then, when Kennedy and Scanlan returned he watched helplessly as Scanlan was killed and Kennedy was attacked from all sides by the Gang.

He later wrote “Kelly incurred no more danger in shooting Lonigan or Scanlan than he would have shooting two kangaroos. He simply gave the men no chance to injure him and might have shot them down without challenging them, as they scarcely had time to realise their danger until they were shot”

At that moment, he made his escape on Kennedys abandoned horse: there was no doubt in his mind that if he stayed he also would have been murdered. Being unarmed, there was literally nothing he could have done to help Kennedy. As he galloped off he was shot at, he was violently thrown from the horse by a low branch and eventually when the horse ‘knocked up’ he continued his escape on foot, spending some time hiding in a wombat hole, terrified the gang would be coming after him. Eventually he carried on in great pain, picking his way in the dark through dense bush and rocky terrain right through the night and most of the next day, eventually arriving at Mansfield at 4 o’clock in the afternoon. He broke the awful news to Sub Inspector Pewtress who immediately set about organising a party to return to SBC to find Kennedy, who was alive and fighting for his life when McIntyre last saw him. McIntyre wrote out a statement, that same afternoon, less than 24 hours after the killings, and it included this account of Lonigans murder:

“…..Suddenly and without us being aware of their approach four men with rifles presented at us called upon us to ‘bail up hold up your hands’. I being disarmed at the time did so. Constable Longan made a motion to draw his revolver which he was carrying, immediately he did do he was shot by Edward Kelly and I believe died immediately.”

McIntyre here reported Lonigan being shot while out in the open and before he had drawn – let alone fired – his revolver. Kellys version, quoted above, was created weeks later and claimed Lonigan ran back to the shelter of logs and came up behind them, gun drawn. This very different account was the basis of Kellys claim only to have killed Longan as an act of self defence. So, who’s telling the truth here – the ‘zealous, conscientious’ policeman or the known liar Ned Kelly?

Despite his serious injuries and exhaustion, McIntyre joined the search party and headed straight back to Stringybark Creek that same Sunday night. When they returned the following day with the bodies of Lonigan and Scanlan, Pewtress wrote that “McIntyre is very ill and suffered great pain while with me”, but on Tuesday ordered him to go and arrest Wild Wright for fighting and unruly behaviour in Mansfield bars. McIntyre does so, drawing his revolver and telling Wright “I’ve just seen my mates shot and if you don’t walk quietly over to the lock-up I’ll shoot you…..”.

Wright responds with a threat, saying something McIntyre was subsequently to hear often: “McIntyre when I heard one of the police had escaped I was glad it was you, I’m damn sorry for it now. You have escaped once, you won’t next time”

The following day, still in pain and suffering, McIntyre returned yet again to Stringybark Creek to continue to search for his colleague, Michael Kennedy, and soon discovered that he had been murdered shortly after McIntyre last saw him. The appalling reality would only just have started to sink in : three colleagues murdered, and somehow he survived.

Subsequently McIntyre was admitted to the police hospital where it was reported that Dr Ford extracted “nearly a pint of blood which was not in circulation” – in other words he drained a massive haematoma which had developed, along with innumerable other scratches and cuts, bruises and contusions that had turned McIntyre’s entire back black and blue. He wanted to join in the hunt for the Kellys but because of the state of his physical health and his nerves, but more importantly his valuable status as the only eye-witness to the murders, Standish wanted him out of harms way. Back in Melbourne, but still working, he married Eliza Fowler as the hunt for the Kelly Gang continued. Three more encounters with Kelly lay ahead of him.

The first was in n June 1880 when Ned Kelly was finally captured at Glenrowan. McIntyre went there to ask Kelly directly, had he displayed cowardice at Stringybark Creek?

Kelly: “No”

McIntyre: “I have suffered a great deal over this affair. Was my statement correct?”

Kelly: “Yes it was”

McIntyre: “When I held out my hands you shot Lonigan”

Kelly: “No. Lonigan got behind some logs and pointed his gun at me. Didn’t you see that?”

McIntyre: “No, that’s only nonsense”

It’s really quite awful to realise that McIntyre’s emotional trauma had so deeply damaged him, so completely undermined his self-esteem and confidence, and so confused and disorientated him that he sought reassurance from the very man who was the cause of all his anguish and distress, the murderer himself. At the trial in Melbourne Kellys lawyer ridiculed him for that visit, saying he had gone there “for a character reference for bravery ; it implies a feeling in his mind that he was guilty of cowardice” Nowadays, seeing McIntyre doubting his own bravery, wracked by guilt over his own survival, struggling with death threats and accusations of cowardice and of having abandoned his mates, we would likely recognise severe depression, anxiety, survivor guilt and post-traumatic stress, a man almost completely disabled by serious mental health issues. Back then no such awareness existed, there was no understanding or help for him, he had to endure the torment and survive being labelled a coward and a liar as best he could. Bracken, another good policeman caught up in the Kelly saga suffered in the same way; it became too much for him and tragically he took his own life. It’s easy to imagine McIntyre doing the same thing…

……to be Continued.

In Part Two of this Post I will detail the rest of McIntyres troubled life, and his testimony in Kellys trial. I’ll also demolish the shoddy arguments that sympathisers in general, and Jones and Crichton in particular promote in the hope that by vilifying Thomas Newman McIntyre they can argue that Kelly wasn’t guilty of Lonigan’s murder. It will be such a pleasure to completely destroy their stupid arguments and to defend the reputation of a very brave Policeman, yet another of the many uncounted casualties of the murderous Kelly Gangs sickening criminal exploits.

Jack Peterson and Alan Crichton among many others promote the fiction that the likes of Ian Jones and Peter FitzSimons wrote in their fictional books, that have sadly been accepted across the board and their lies have been transformed into ‘facts’. Fortunately, that is now being addressed and in time all the myths, lies and fiction will be exposed and replaced with factual information that shows the men they degrade were almost all decent family men who were serving their communities as police officers and keeping them safe from the likes of Ned Kelly and his Greta thugs.

When matters relating to police officers being wrongly accused have been brought to notice and proved to be complete fiction, they ignore the facts and continue with their lies and degradation of good, decent men. Morons, the lot of them.

All of those mentioned above were and are anti-police. Their writings and behaviours are deplorable….

Most of the people you cite are simply recycling the toxic nonsense that Ian Jones introduced them to. None of them has ever really seriously stopped to take a look at the evidence and to look at Sadleirs “Recollections” to see if what Jones has told them about it was accurate or not.

No reasonable person who ever bothered to do that, or think about the character of the two men whose opposite views are being evaluated would ever take the side of the already proven liar and conman Ned Kelly over a ‘zealous and conscientious’ policeman with a history of having been a hard worker and a much loved school teacher. McIntyre was an industrious young man who kept himself in useful employment from a young age, but he was also ambitious and adventurous, bringing himself on his own to the Colonies presumably seeking a better life for himself. Contrast that to the lazy thief and liar Ned Kelly who became a criminal because he decided he was above honest hard work for a weekly wage.

His encounter with Kelly was to cast a dark pall over the rest of his life but thank god by his bravery quick thinking he managed to survive SBC and live to make sure Kelly ended up in Court and receive his just deserts.

Kelly lovers can get up close and personal with this Kelly portrait shower curtain, https://fineartamerica.com/featured/ned-kelly-mugshot-1880-war-is-hell-store.html?product=shower-curtain

Get head by Ned

Attachment

Its not even a mugshot!

Its a fancy portrait by Charles Nettleton.

Here’s the actual mugshot. Imagine that on a shower curtain. Creepy.

Hi David, the claim that McIntyre perjured himself in his account of the murder of Lonigan originated with Ian Jones in the 1967 Wangaratta Kelly seminar, published in the 1968 Man & Myth book, p. 142, at the start of his comments on Louis Waller’s legal chapter. He introduces Sadlier’s 1913 recollection of McIntyre’s story of the SBC murders and says, “Sadleir suggests that McIntyre committed perjury at Kelly’s trial and in all sworn statements in connection with the murder of Lonigan subsequent to the accout he gave to Sadleir.”

As with many things Jones imagined, this too is way off beam, but that has not stopped the Kelly nuts uncritically echoing it for the last 54 years. It is a very well entrenched fairy tale and has also been echoed by several legal eagles who relied on Jones the bungler for their historiography.

If Jones’ claim about Sadleir’s memoir were true, then the legal eagles’ conclusions may possibly follow. Buty if Jones’ claims are false – as they are – he has led a lot of them to feats of extraordinarily stupid.wrong-headedness. Lettuce consider:

Jones’ claim of McIntyre’s perjury rests on what he claims is Sadleir’s transcription of McIntyre’s first statement in his memoir, that has Lonigan getting behind a log. Where the blunder is, as Jones should already have known full well in 1967, and unquestionably knew backwards before he wrote ‘Short Life’ decades later (1995), is that McIntyre’s first statement is in the Prosecution file in the VPRO. Sadlier did not use McIntyre’s first statement as a refrence, and did not trranscribe it, or even from it, in his memoir. The only “perjurer” here is Jones, presenting his own half-baked slovenly research as truth.

Jones said there p. 142 that “Sadleir suggests that McIntyre committed perjury at Kelly’s trial” and elsewhere. This is clearly a fabrication: Sadlier said no such thing in his memoir or anywhere else. What Jones means is that Jones’ peculiar interpretation of Sadleir as quoting from a transcript of McIntyre’s first statement suggests that McIntyre committed perjury. Instead, Sadlier used conventional quote marks to indicate and mark off what he recalled McIntyre having told him from the rest of his text. There is nothing to do with a transcript implied anywhere. Once again, Jones made it up to fit his idiotic attempt at justification of Kelly’s murder of Longan. He really made a huge cock-up of practically every part of the Kelly story. How his Short Life book ever got a reputation as a reliable biography is beyond me, but I put it down to nobody ever doing any critical research into it and checking his source references for what they actually said, rather than relying on Jones’ interpretation of them. The Sadlier bungling here is a classic example of this extraordinary incompetence and its persuasively written and romantically bewitching influence on many people and especially academics who ought to have known better

Jones also bungled the dates of Sadleir’s arrival and departure from Mansfield during that time, but we can deal with that another day.

Some further detail: According to Jones, Sadlier quoted from “the shooting as described by … McIntyre in his first-ever account of the Stringybark Creek tragedy [and] showed that Kelly acted in self-defence”. (Ian Jones, “Introduction”, in Roger Simpson, The Trial of Ned Kelly, (Richmond: Heinemann, 1977), viii. Jones seems to have alternated between this belief and acknowledging that Sadleir placed the story he related two days after the shootings, and was thus not McIntyre’s first account, while maintaining that “Sadleir[‘s version] suggests that McIntyre committed perjury” (Jones, comment, in C. Cave, ed., Man & Myth, 142).)

This belief was likely based on newspaper reportage of Kelly’s August 1880 committal hearing, in which McIntyre stated in cross-examination, “My first report, in writing, was to Superintendent Sadleir. … I have not seen the report since, and as it was written two years ago, I cannot remember all that was in it” (Daily Telegraph, 9 August 1880, 3).

McIntyre’s “first ever account” was written immediately upon his return on 27 October at 4pm, before going out again two hours later with a party of police and volunteers to search for the bodies of the slain police. That account was sent to Sadleir attached to a letter written by Pewtress the same evening, 27 October (Letter, Pewtress to Sadleir, 27 October 1878, VPRS 4965, Unit 3, Item 172)..

It says, “Lonigan made a motion to draw his revolver which he was carrying, immediately he did so he was shot by Edward Kelly and I believe died immediately” (McIntyre to Pewtress, Mansfield, 27 October 1878, VPRS 4966, Unit 1, Item 1, pp. 10-12 of the PDF file.)

It is not the story recalled by Sadleir over 30 years later, which reflects Kelly’s publicised accounts (Sadleir Recollections, 186). Jones mistook the story in Sadleir for McIntyre’s first report, an inexcusable blunder given his intimate knowledge of the police files. The resulting damage was significant, as it led Jones to visciously portray the scrupulously honest McIntyre ever after as a perjurer, man who had repeatedly lied on oath to secure Kelly’s conviction.

Sadleir visited McIntyre shortly after the shootings not to obtain a statement, which McIntyre had already provided to him, but “to set him at ease” about the “stupid and cruel” stories that to spoke of his “escape from escape out of the hands of the Kellys – from the very jaws of death – as desertion of his comrades”. Sadlier next said, “His story, as he then told it to me, was this,” and gave a two paragraph summary of the Stringybark encounter.

As Sadleir recalled it, McIntyre said that “suddenly Lonigan and I heard the call to throw up our hands, and saw four armed men, partly concealed by the timber, covering us with their guns. I had no weapon but a small table-fork, and I threw up my hands. Lonigan was sitting on a log, and on hearing the call to throw up his hands, he put his hands to his revolver, at the same time slipping down for cover behind the log on which he had been sitting. Lonigan had his head above the level of the log and was about to use his revolver when he was shot through the head. Then the four men rushed in”.

In support of his view that McIntyre had given “a statement to Supt. Sadleir”, Jones argued that “a clear indication that Sadleir is carefully transcribing [is] the use (and bracketed correction) of third person instead of first … ‘the horse moved towards him (McIntyre) … ‘”. As a scriptwriter himself, Jones was well aware that such a clarification in relating a story does not imply transcription. As is obvious from McIntyre’s written statement to Sadleir preserved in the police files, the very different story in Sadleir’s memoir is a faulty recollection of his talk with McIntyre. It was certainly not a “statement” by McIntyre.

Next comes what is vital to understanding the poisoning of McIntyre in the Kelly literature, especially by high-flying lawyers, for the last 50+ years: Based solely on Jones’ false assertion that Sadleir’s narrative was a “verbatim” account by McIntyre, Professor of Law Louis Waller pronounced that “the accused … is entitled to have the jury know that a witness has not always told the same story. That is why counsel is so anxious to find discrepancies between what is recorded in the depositions taken at the preliminary inquiry and what a witness has to say when he is giving evidence at the trial itself”.

Waller held that McIntyre’s report to Pewtress of 28 October 1880 contained “the same sort of statement”, that Lonigan “made a motion” toward his gun when he was shot, thereby equating a “motion” to draw his revolver, as McIntyre described in every account, with having actually drawn and aimed his revolver at Kelly in the version in Sadleir. In accepting Jones’s belief that Sadleir’s recollection was a “verbatim account” by McIntyre, Waller became the first of many legal experts to contend, “That McIntyre made previous inconsistent statements, and that he had made them very shortly after the event … should have been put to the jury. Those previous inconsistent statements should have been put fairly and squarely to him”.

If, however, Jones was wrong in that Sadleir’s text was not a verbatim report but a faulty recollection, then McIntyre’s statements about the death of Lonigan were consistent, and much that has been written against him falls apart. The only question is how long it will take the Kelly nuts to retract their 54 years of error.

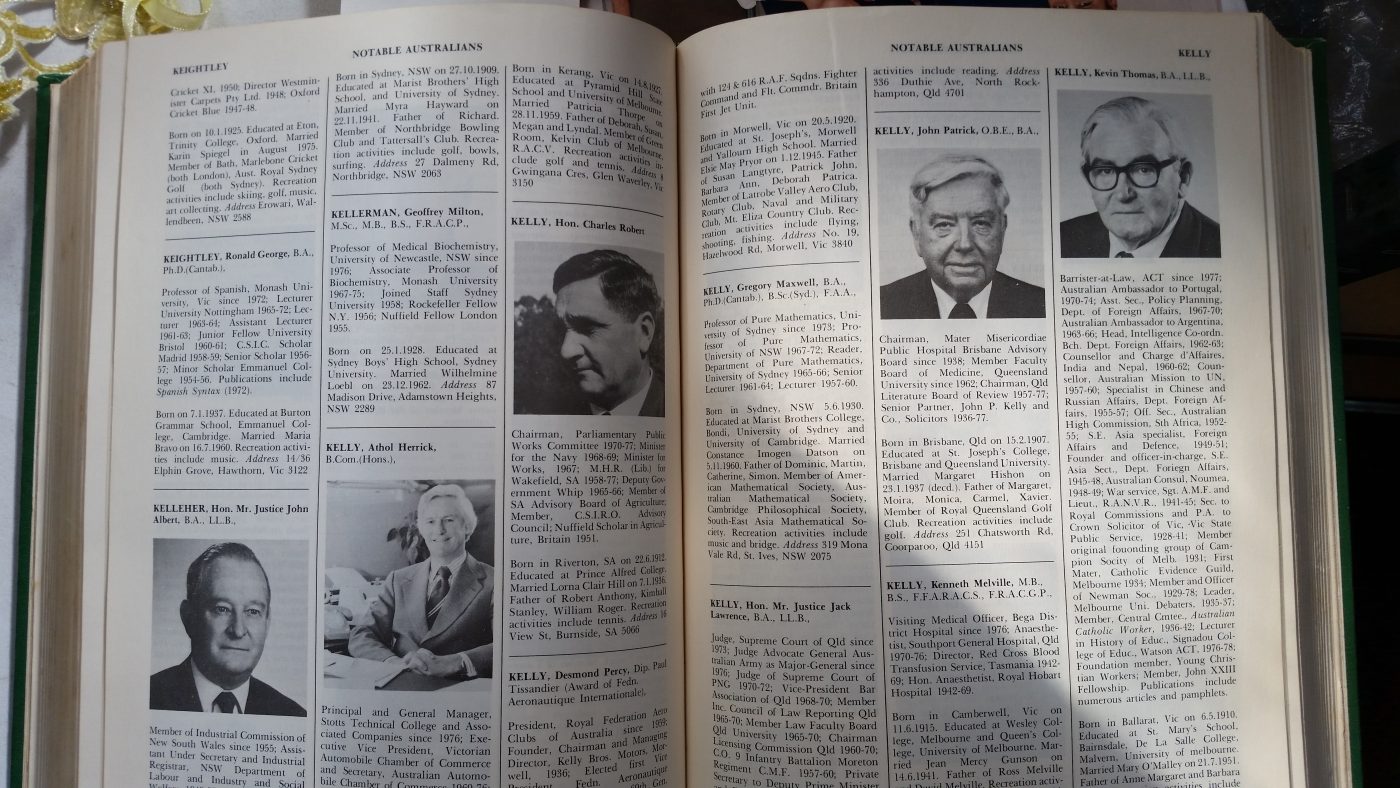

Ned Kelly is not mentioned in “Notable Australians – a pictorial who’s who”, 1978. He seems to have been something of a minority special interest, along with other bushragers, until perhaps the outpouring of Kelly books in 1980 produced for the centenary of his hanging.

I have just read through George Farwell’s 1970 “Ned Kelly” book. It is very light reading and contains no source references for anything he says. It came out the same year as that dreadful Mick Jagger Kelly film, and contains a couple of stills from the movie. Nearly half of it consists of the text of Kelly’s two letters, the RC’s Second Progress Report, a 2 page list of convictions of the Kellys, Quinns and Lloyds from the 1881 Royal Commission, and a transcription of Constable Gascoign’s first draft report of what he witnessed at Glenrowan (which is worth reading as not otherwise available that I know of). His bibiography show that he has read Cave’s Man & Myth book (1968), Kenneally’s Inner History, Brown’s Australian Son, Hobsbawm’s 1970 Bandits, and Russell Ward’s overtly Marxist “The Australian Legend”, amongst other things; so all pro-Kelly material with a general Trotty leaning.

As such it is a representative overview of the state of Kelly myth in 1970, which might be called flamboyant. and very pro-Kelly – he speaks of “our outlaw” p. 101 in the context of discussing Australian mateship. Back then no-one knew about Kelly’s part in lagging Harry Power, or his complicity in killing Aaron Sherritt via the assistance of Dan; or his shooting Metcalf in the face at Glenrowan with Piazzi’s revolver, etc.

Most tellingly for the development of Kelly mythology, he gives only Kelly’s account of key events taken from the Jerilderie letter. On p. 26 he gives Kelly’s story of the McCormick incident as fact, not bothering to present Hall’s account from the newspaper of the day as a counterpoint. On p. 33 he gives only Kelly’s account of the Stringybark Creek murders: “But let Kelly tell the story for himself.” There is almost no analysis anywhere; it is just a Kelly story taking Kelly’s side, with factual errors all over the place. The pattern of taking what Kelly said as fact and using that to challenge police records and personal witness accounts would go on to infect much writing about Kelly through into the 1980s and beyond.

Attachment